Battle Hymn

This is a bonus edition of A Public Witness. If you are only signed up for a free account and like what you read, please consider subscribing today. For just $5 a month, we’ll deliver insightful analysis about religion, politics, & culture to your inbox every week. Once you start a paid subscription, you can also read the archives, like Tuesday’s issue on the fall of Afghanistan or last week’s issue on opportunity costs.

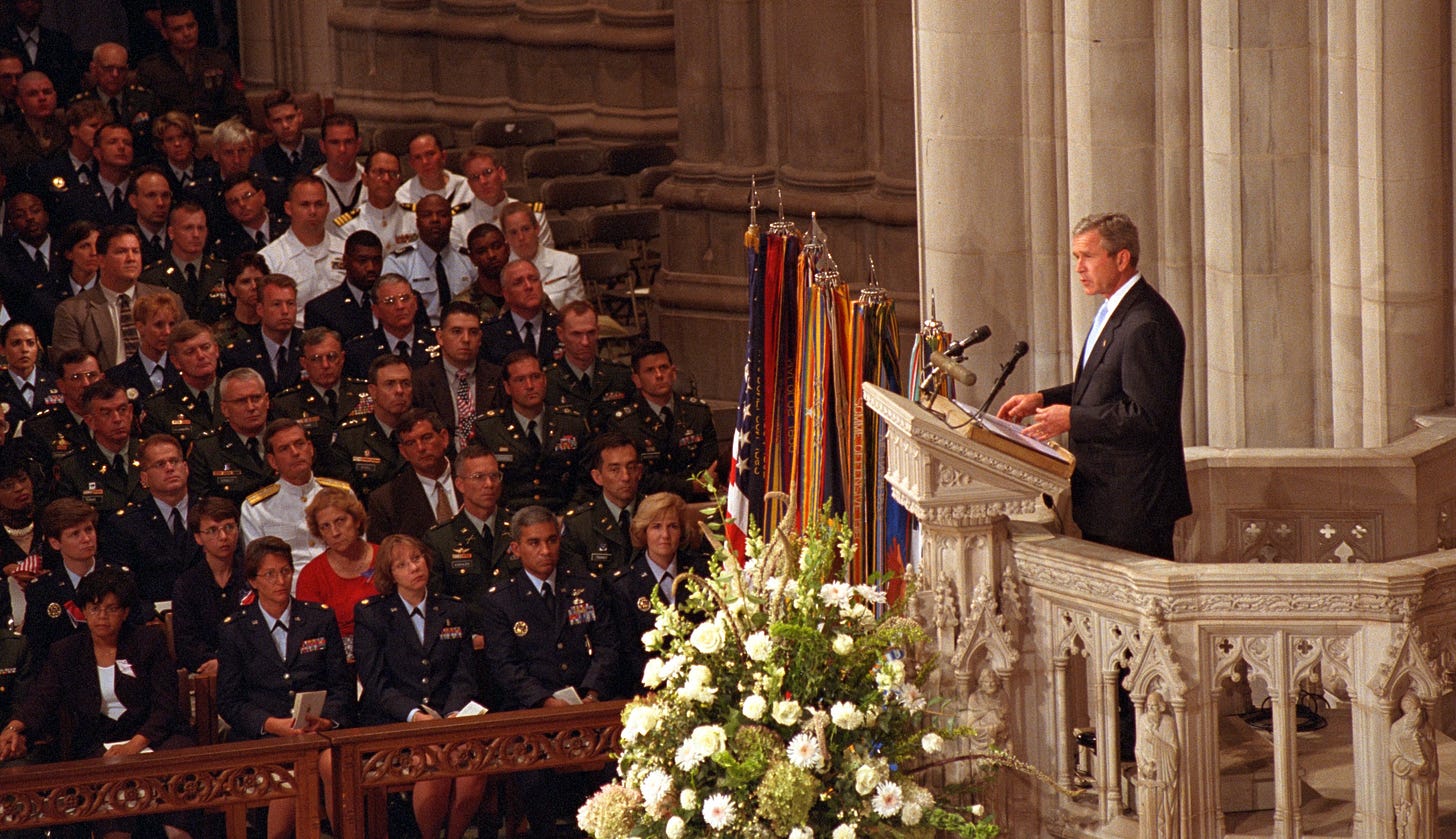

President George W. Bush stepped down from the pulpit in the National Cathedral three days after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. As he took his seat, the U. S. Navy choir, the Sea Chanters, led the congregation in the closing hymn for the service.

“Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord. He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored. He has loosed the fateful lightning of his terrible swift sword.”

The crowd of politicians, uniformed military officials, and others stood to join the singing of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” a militaristic song written in the midst of the U.S. Civil War. In the hymn, the singers proclaim they have God on their side and, thus, will prove victorious in war. The U.S. flag and those of the country’s military branches stood near the altar.

“I have read a fiery gospel writ in burnished rows of steel.”

The song echoed in the massive sanctuary with patriotic fervor following the sermon by Bush, where he promised America will “answer these attacks and rid the world of evil.” Bush also declared God would bless the nation’s cause: “They have attacked America because we are freedom’s home and defender, and the commitment of our fathers is now the calling of our time. On this National Day of Prayer and Remembrance, we ask Almighty God to watch over our nation and grant us patience and resolve in all that is to come.”

“He has sounded forth the trumpet that shall never call retreat.”

During the service, Rev. Kirbyjon Caldwell, a United Methodist pastor in Houston, Texas, who subsequently ran into legal trouble, read Psalm 27:1-3,13-14 to baptize the upcoming conflict. This passage uses military language to assure the congregation not to fear because God is present: “Though an army encamp against me, my heart shall not fear; though war rise up against me, yet I will be confident.”

“I have seen him in the watch-fires of a hundred circling camps.”

The other main preacher for the service joined the president in promising divine assistance in winning the coming war. Billy Graham proclaimed, “We’re facing a new kind of enemy. We’re involved in a new kind of warfare. And we need the help of the Spirit of God. The Bible’s words are our hope: God is our refuge and strength; an ever-present help in trouble.” Graham added, “We also know that God is going to give wisdom and courage and strength to the president and those around him. And this is going to be a day that we will remember as a day of victory.”

“As he died to make men holy let us die to make men free, while God is marching on.”

After the benediction following the hymn, the military honor guard led the U.S. flag and the military flags out of the sanctuary. Then the priests followed with the cross — the same order in which they had walked into the holy space over an hour earlier. That order proved predictive. In the days that followed, most U.S. Christians would follow Bush and the military in cheerleading an invasion of Afghanistan.

As the U.S. mission in Afghanistan now falls apart in apocalyptic fashion, it is important we learn from this failure. While we offered key takeaways from this moment in Tuesday’s issue of A Public Witness, in this bonus issue we shift our focus from political mistakes to the spiritual realm. The integrity of the American Church’s public witness in the future demands revisiting our role two decades ago in lending support to the tragedy that ultimately unfolded.

Onward Christian Soldiers

When a war starts, many in an impacted nation will quickly rally around their flag and leader. Polling in October 2001 showed more than 90% of Americans supported military action in Afghanistan. The authorization for use of military force passed the U.S. Senate 98-0 and the U.S. House 420-1 (with both votes occurring later on the same day after the National Cathedral service featuring Bush and Graham). U.S. Christians largely found themselves giving into this siren song following the horrific events of 9-11 — and in some cases singing the hymns of Christian Nationalism to convert others to the cause of war.

Mark Galli, then-managing editor of Christianity Today (the nation’s flagship Christian news magazine), warned in the Oct. 22, 2001, issue about the danger of allowing revenge to drive the U.S. response. But he also criticized voices pushing for peace for offering what he derided as “cowardly compassion.” Thus, he urged Christians to back the war effort — even if it meant engaging in ungodly behavior.

“This course requires courage because it means risking one’s moral purity in the pursuit of justice. And that means the pursuer must depend on the grace of God for his justification, because when he is done acting on the historical stage, he will surely not be able to point with any pride to his pure works,” Galli wrote.

And then he baptized the war effort.

“This struggle must be waged on a variety of fronts: Christians praying always and everywhere; missionaries and local believers hazarding their lives in sharing the gospel in the most religiously repressive settings; relief agencies and local congregations refusing to discriminate in distributing aid to the needy; Christian diplomats employing all the wiles of their craft; and, yes, Christian fighter pilots, navy personnel, and infantry insisting, when other options are exhausted and military force is called for, that liberty must be respected and justice done,” Galli argued.

An unsigned Christianity Today editorial in the next issue, Nov. 12, went even further by arguing “it may be time to put the American flag back in American churches.” (We’re not sure when CT thinks the flags that went up to promote the two world wars actually went away, but the mentality of the editorial is still stunning.) The editorial was titled “Rally Round the Flag,” with a subtitle of “America may not be God’s chosen nation, but it does have a mission that churches can support.”

The editorial included a drawing that depicted a fish symbol with the word “Jesus” written in the middle. It was a common sight on car bumpers back then, except this Jesus fish, in apparent sincerity, proudly held up an American flag.

And the piece, of course, cited Romans 13 about government wrath but not the teaching just four verses earlier in Romans 12 about not overcoming evil with evil.

“We believe it is a time for churches to recommit themselves to our nation and to its highest purpose,” the editorial added. “We should once again plant ‘the flag’ — the national pursuit of liberty and justice for all — in the midst of our churches’ life and mission.”

Other Christian leaders also waved the flag for a “just war” in Afghanistan, utilizing a centuries-old paradigm designed to limit war but in modern times often used to justify any war. The Southern Baptist Convention’s Executive Committee passed a resolution just one week after 9-11 citing Romans 13 and saying they “pledge hearty prayer and unreserved support for our president, his advisors, Congress, and the members of the armed forces as they fulfill their God-given duties in responding to this attack.” Many SBC leaders also made the religious case for war.

“When all the diplomatic efforts to secure justice fail, the only way to safeguard our nation is to strike at the source of this evil. The 13th chapter of the Book of Romans tells us government has the biblical authority to use lethal force to exact justice,” argued Richard Land, who at the time led the the SBC’s Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission. “If you want to get rid of the malaria of international terrorism, you just can’t swat mosquitoes; you have to drain the swamp.”

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, who would later oppose the Iraq invasion, offered support for the military intervention in Afghanistan. Noting that “the Church has sanctioned the use of the moral criteria for a just war to allow the use of force by legitimate authority in self-defense and as a last resort,” the bishops argued the Afghanistan mission met that standard. The conference voted down a plea from one bishop who urged a nonviolent response as part of a “return to the original teaching of the Church.”

Jean Bethke Elshtain, who taught political ethics at the University of Chicago Divinity School, defended the “just war” perspective in an essay for the Nov. 14, 2001, issue of Christian Century that included alternative perspectives like Glen Stassen arguing against the bombing of Afghanistan in favor of “just peacemaking” efforts. Elshtain, on the other hand, asserted, “The course charted thus far by the U.S. has been complex, nuanced, restrained. … This is responsible action.”

Russell Moore, then a Christian theology professor at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, wrote a Baptist Press column published Oct. 8, 2001 (the day after the U.S.’s “Operation Enduring Freedom” started in Afghanistan). Moore criticized mainline Christian leaders for in recent years having “decided that some hymns simply had to go. The first to get the axe was ‘Onward Christian Soldiers.’ After all, it was argued, the song is too militaristic. It is too ‘masculine.’” With the U.S. attacking Afghanistan, Moore now wanted to make sure that churches joined the war effort.

“America is at war. For many of us, the patriotic anthems of our homeland never have been more welcomed,” Moore wrote. “Let’s sing our hymns. Onward, Christian soldiers.”

Another Way

We recount these examples, knowing there were many others, to spark reflection. With the short-term memories that too often guide contemporary politics, there is a danger in forgetting how we ended up somewhere. And then we fail to avoid making the same political and moral mistakes in the future. So, history repeats. Vietnam. Afghanistan. Iraq.

Bringing justice to the non-state terrorists who perpetrated the attacks on 9-11 did not necessitate the broader pursuit of regime change and nation-building. The moral rightness of accomplishing the former should be separated from the evaluation of pursuing the latter purposes.

Let’s be clear: the two-decade military intervention in Afghanistan did not meet the principles of a “just war.” It was not a last resort option but one quickly launched less than a month after the attack. There was not, as is now clear, a reasonable chance of success. The violence that came was not proportional; in response to losing almost 3,000 citizens, we launched a military effort that led to the deaths of more than twice that many Americans and more than 15 times as many Afghan citizens.

And there were warning signs. There were voices crying out in the political and theological wilderness trying to tell us this wouldn’t end well.

“Bush said the war on terror ‘will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped, and defeated.’ Such an ambitious goal fails to pass the test of just war theory,” argued Robert Parham of the Baptist Center for Ethics. “The promise to rid the world of terrorism reflects the dangerous ideology of purity. It bumps against the line of holy war in which crusaders believe the world may be purified from evil.”

The board overseeing social issues for the United Methodist Church (Bush’s denomination) warned that “military actions will not end terrorism.” They added, “War is not an appropriate means of responding to criminal acts against humanity.”

Others also preached against war as fundamentally in conflict with the teachings of Jesus.

“Nonviolence and what it means to be a disciple of Christ are constitutive of one another,” theologian and longtime Duke University professor Stanley Hauerwas said to explain his opposition to the Afghanistan mission. “So many people are on a kind of God-and-country bandwagon right now. That’s very sad, from my point of view.”

Ultimately, the push for war from many U.S. Christians appeared to merely echo Bush’s call with a little more religious language. That led David Gushee, then a professor at Union University in Tennessee and now at Mercer University in Georgia, to lament that there did not seem to be “a distinctive Christian voice at a time like this.”

“Is this all there is to the Christian witness at a time like this?” he added. “Are we as Christians content merely to bring out the just war theory, run through the categories, see that our nation is justified in making war, and then sit back and watch the bombs fall?

That’s the question that motivates our analysis today. Although some sounded prophetic warnings, most American Christians quickly fell in line, just like the priests in the National Cathedral dutifully carried the cross behind the U.S. and military flags.

We will not claim to be prophetic but we seek to be realistic: There will be another call to war someday. Perhaps next year, perhaps next decade, perhaps the one after that. At some point, an American president will give the call that comes to each generation: Take up arms and go kill those people over there. The question, then, is not if our nation will seek another way but if the cathedrals will ring their bells in support.

We cannot wait until that moment to unpack Christian teachings relevant to the questions of war. At the point that members of Congress are singing “God Bless America” and a president is saying let’s go get rid of “evil,” it’s too late to start Sunday School classes about war, peacemaking, and Christian ethics. We need to start discipleship toward Christian formation before the bombs start falling. That’s why as the Afghanistan mission ends, we need to remember how it started.

If we do the hard work now, it might just make a difference in the future. For while Bush, Graham, and others were singing the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” and marching as to war, Rep. Barbara Lee of California heard a remark by Nathan Baxter, dean of Washington National Cathedral. Later that day, she explained why she would become the only one of the 535 members of either the U.S. House or Senate to vote against the authorization of military force.

“Let’s just pause, just for a minute, and think through the implications of our actions today, so that this does not spiral out of control,” Lee said. “I have agonized over this vote. But I came to grips with it today, and I came to grips with opposing this resolution during the very painful, yet very beautiful, memorial service. As a member of the clergy so eloquently said, as we act, let us ‘not become the evil that we deplore.’”

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor & Beau Underwood