Did the Fundamentalists Win?

The pastor’s sermon got him in trouble. It sparked national media attention, criticism from other pastors, and an investigation from his denomination that ended with the pastor’s resignation. But this controversy wasn’t about a minister who challenged COVID disinformation, QAnon conspiracies, or a political cult of personality.

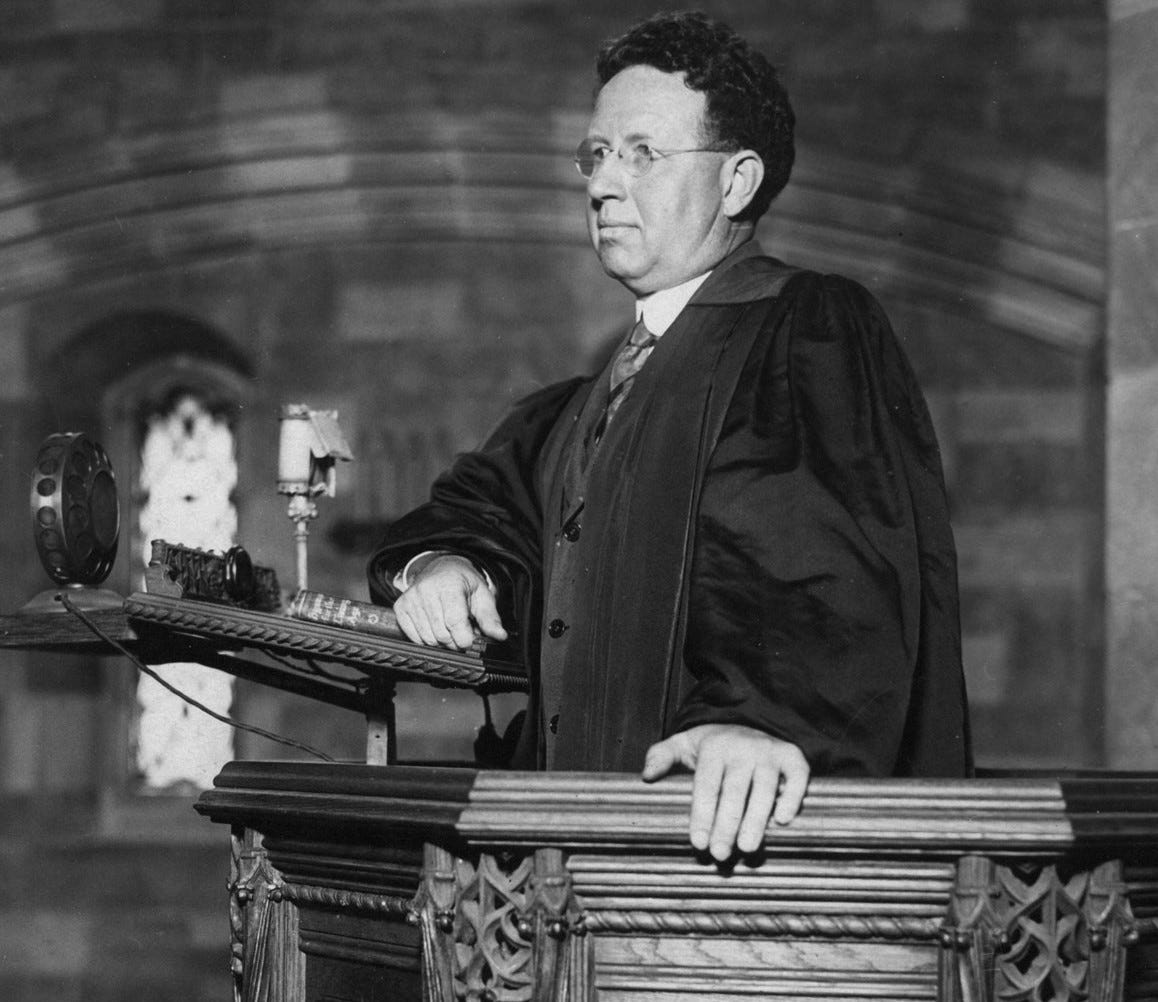

When Harry Emerson Fosdick, a Baptist minister, was called to preach at First Presbyterian Church of New York City in 1918, he assumed the role as a war in Europe wound down and as a two-year global pandemic started to fire up. For the next six years, he preached at the “Old First” church on Fifth Avenue whose history went back two centuries.

This was a time of change and promise animated by scientific discoveries and technological advancements. But with these societal shifts came religious uncertainty and conflict. As historian Diana Butler Bass explained recently at her Substack newsletter The Cottage, some Christians “worried that churches were succumbing to the spirit of modernism and they set themselves against other Christians — Harry Emerson Fosdick included — whom they considered heretics.”

“America was rapidly becoming more cosmopolitan, more global, and more inclusive than it had been just decades before. Churches struggled with the changes,” she added.

In that context, Fosdick took to the pulpit of Old First on May 21, 1922, and preached his most famous sermon, “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?” In today’s terms, we would say it went viral. Uberwealthy industrialist John D. Rockefeller Jr. paid to print and distribute 130,000 copies of it (we’re open to such a system of patronage today if anyone’s interested). This sparked counter-sermons and publications, like “Shall Unbelief Win?” by a Presbyterian pastor in Philadelphia.

The next year, the national convention of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the USA — which later merged with another Presbyterian group to create the Presbyterian Church (USA) — ordered Fosdick’s local presbytery to investigate his views. A candidate for moderator of the denomination, William Jennings Bryan (a former U.S. Secretary of State and three-time Democratic nominee for president), was among the Presbyterians speaking against Fosdick. Serving as Fosdick’s defense counsel was John Foster Dulles, a future U.S. Senator and Secretary of State (and namesake of an airport). But ahead of a likely censure at a denominational trial in 1924, Fosdick resigned.

Fosdick returned to a Baptist church after that — until Rockefeller financed the building of a new church to give Fosdick a bigger platform. Thus was born the famed Riverside Church in New York. From that pulpit, Fosdick continued to impact American religious and political life, as evidenced by his appearing on the cover of Time magazine. Martin Luther King Jr., who famously preached an anti-war sermon at Riverside in 1967, called Fosdick “the greatest preacher of this century.”

While Fosdick’s career survived the initial victory of the fundamentalists who drove him from Old First, the question raised by his sermon remains. As Bass argued, “The Fundamentalist-Modernist controversy is a long shadow hanging over the last century” as evidenced by the fact that “we experience its continued influence every day in our churches and in our politics.”

Thus, this sermon that cost one of the nation’s most famous preachers his job warrants a look back 100 years later. In this issue of A Public Witness, we reconsider Fosdick’s sermon and ask some of American Christianity’s leading voices and experts, “Did the fundamentalists win?”

That Will Preach

As Fosdick stepped into the pulpit on May 21, 1922, he sought to make a simple point: Those masquerading as the true defenders of Christianity were actually damaging the life and witness of Christ’s Church. Noting that “there are no two denominations more affected by them than the Baptist and the Presbyterian,” the Baptist preaching in a Presbyterian church made the case against those demanding purity tests that drove people away from Jesus.

From the outset, Fosdick clarified that “not all conservatives are fundamentalists.” His ire wasn’t toward those who hold specific doctrines, for as a self-proclaimed “liberal” he defended the “right to hold these opinions.” Rather, he criticized the “illiberal and intolerant” approach of fundamentalists.

He rightly located fundamentalism’s rise as a backlash to the expansion of scientific knowledge. New discoveries about the physical universe and the unfolding of history challenged understandings of the Bible and Christian faith. Rather than revise their beliefs in light of these ideas, fundamentalists pitted faith against reason. Fosdick spoke up for those resisting this dualism.

“There are multitudes of reverent Christians who have been unable to keep this new knowledge in one compartment of their minds and the Christian faith in another. They have been sure that all truth comes from the one God,” he preached. “That they might really love the Lord their God, not only with all their heart and soul and strength but with all their mind, they have been trying to see this new knowledge in terms of the Christian faith and to see the Christian faith in terms of this new knowledge.”

“Now, the people in this generation who are trying to do this are the liberals, and the fundamentalists are out on a campaign to shut against them the doors of the Christian fellowship. Shall they be allowed to succeed?” Fosdick added.

As specific examples, Fosdick noted fundamentalist teachings on miracles reported in scripture, the meaning of biblical inspiration (specifically the fundamentalist belief in inerrancy), and the nature of the second coming of Jesus. Fosdick explained that faithful Christians can disagree on these issues: “Too often we preachers have failed to talk frankly enough about the differences of opinion which exist among evangelical Christians, although everybody knows that they are there.” Fundamentalists, however, make these doctrinal debates litmus tests that would have excluded from fellowship many Christians throughout history.

“[Fundamentalists] say the liberals must go. Well, if the fundamentalists should succeed, then out of the Christian Church would go some of the best Christian life and consecration of this generation — multitudes of men and women, devout and reverent Christians, who need the church and whom the church needs,” he argued. “Do we think the cause of Jesus Christ will be furthered by that? If he should walk through the ranks of his congregation this morning, can we imagine him claiming as his own those who hold one idea of inspiration [inerrancy] and sending from him into outer darkness those who hold another? You cannot fit the Lord Christ into that fundamentalist mold.”

Fosdick also criticized fundamentalists for trying to codify their narrow religious beliefs into law (apparently some things never change): “[Fundamentalists] have actually endeavored to put on the statute books of a whole state binding laws against teaching modern biology.”

Instead of purity tests and purges, Fosdick advocated for “a spirit of tolerance and Christian liberty” that respected the God-given conscience of each person. He also lamented the opportunity costs of the fundamentalists’ fight. Christians should develop “a sense of penitent shame that the Christian Church should be quarreling over little matters when the world is dying of great needs.”

Fosdick claimed that he did “not believe for one moment that the fundamentalists are going to succeed” with their “immeasurable folly.” Of course, just two years later they forced him from that very pulpit. But even if that didn’t temper his optimism, what might be said today with the wisdom provided by a century of hindsight?

Evidence that Demands a Verdict

Ahead of the sermon’s centennial anniversary on Saturday, we asked prominent Christian scholars, pastors, and activists for their contemporary response to Fosdick’s question.

Fosdick believed the fundamentalist wouldn’t win, and Will Willimon, a Duke Divinity School professor and retired United Methodist bishop, agreed they didn’t. But he offered that opinion with a twist of irony that much of the evangelical church came around to Fosdick’s approach.

“The fundamentalists didn’t win,” Willimon, author of Preachers Dare: Speaking for God, told us. “Fosdick’s liberalism triumphed, if by ‘liberalism’ we mean the reduction of the gospel to an appeal to individuals to make an individual verdict on the gospel, the characterizing of the gospel as a set of principles and beliefs, and a disparagement of the church as the way Christ has chosen to save the world. We’re all liberals now.”

“If you don’t believe that mid-twentieth century liberalism has won, just listen to the sermons of Andy Stanley or Joel Osteen or T.D. Jakes,” Willimon added. “The Bible that mid-century fundamentalists staunchly defended (though with thoroughly modern means of thought) plays only a subsidiary role in much so-called evangelical preaching.”

Perhaps the evaluation depends on the definition of “won.” Where Willimon sees a defeat, historian George Marsden, author of Fundamentalism and American Culture, noted a victory: “Fundamentalists, in the broad sense of those holding to fundamental evangelical doctrines, have in the long run surpassed the liberal Protestant movement. Something like 31% of 21st century Americans affirm that ‘the Bible should be taken literally.’ 34% reject biological evolution of humans (contrast that to 9% in Great Britain).”

Yet, Marsden also told us he sees some loss since “‘fundamentalist’ is rarely used as a self-designation today and the remnants of a specific fundamentalist movement are fragmented. Critics still sometimes apply the term to the most militant wing of White evangelicals. Unlike the 1920s, much of the strongest militancy involved is shaped by party politics.”

Christian ethicist David Gushee, author of Introducing Christian Ethics (and a Word&Way board member), similarly sees a shift in labels amid a growing partisan focus.

“[Fundamentalists] did win religious dominance (shared with conservative Catholicism) of the conservative part of the White population in the United States. One way they did this was for a considerable number of them to rebrand as ‘evangelicals,’ a more appealing term without the hardcore historical baggage,” he told us. “Once labeled evangelicals, they built a large number of powerful church and parachurch organizations. Eventually evangelicals and fundamentalists (if the difference is meaningful) became deeply invested in a political marriage with the Republican Party to ‘take America back for God.’”

“The main result by now appears to have been a religious drift and moral collapse into MAGATrumpist toxicity,” Gushee added before raising the question asked in Matthew 16:26: “For what will it profit a man if he gains the whole world and forfeits his soul? Or what shall a man give in return for his soul?”

Others pointed to that partisan element, with some perceiving the victory as not only lamentable but also pyrrhic in terms of the original goal of preserving doctrinal purity.

“Did the fundamentalists win? Yes, but at a fearsome cost,” Dartmouth historian Randall Balmer, author of Bad Faith: Race and the Rise of the Religious Right, told us. “Fundamentalists had carved out for themselves a secure, albeit marginal, space on the landscape of American evangelicalism, insisting as they did on such issues as biblical inerrancy, creationism, and separation from the broader culture. The venture into politics in the mid-1970s to defend racial segregation in their institutions, however, initiated a process that hollowed out fundamentalists’ claims of biblical fidelity.”

This march by fundamentalists like Jerry Falwell Sr. “into the political arena in search of political influence and cultural relevance,” Balmer added, led to theological losses: “The merger of fundamentalism with the far-right precincts of the Republican Party has produced an agenda at odds with both the New Testament teachings of Jesus and the noble heritage of evangelical social activism in the nineteenth century.”

Social ethicist Miguel De La Torre, author of Decolonizing Christianity, echoed that critique: “I’m not sure if the fundamentalists won, but I have no doubt that its heir, White Christian Nationalism, rules the day. This fundamental merger of White Supremacy and fundamentalism has given us an evangelicalism that has choked all spiritual life out of Christianity, turning the message of Jesus into an apologist for a Trumpish faith which serves as the antithesis of the gospel message. What was once good news of unconditional love has become the greatest threat to humanity.”

Michael Livingston, the interim senior pastor of Riverside Church, expressed similar concerns about the consequences of this victory in last week’s episode of Dangerous Dogma: “It does seem the fundamentalists in some ways have won. They’re about to overturn Roe v. Wade on the Supreme Court. They have rolled back voter protections from civil rights legislation in the mid-60s. Some fear that gay marriage will be next on the agenda. These would be initiatives, movements, and developments in liberal Christianity that have been targets for fundamentalists.”

Brian D. McLaren, author of Do I Stay Christian?, also wants to move Fosdick’s question from the last century to the next. In fact, he preached earlier this month at Old First on “Shall the 21st Century Fundamentalists Win?”

“Now, religious fundamentalisms around the world have remarkable similarities,” McLaren told us. “They have a taste for authoritarian leaders who promise them power, privilege, and protection. They ignore the reality of climate change, they fear or deny science, they are quick to scapegoat ‘the other’ and use violence, and they are prime targets for propaganda and conspiracy theories. It’s time for all of us to wake up to the dangers of 21st century fundamentalism, or else we will all lose.”

A Live Question

A lot changed in the last century. Today we have life-saving vaccines to combat pandemics. Electronic communication sped up from the early days of short-distance radio to devices in everyone’s pockets instantaneously sending messages around the world. And our society has moved from a place where only White people could vote across the country — with women just two years into that status — to a multiracial democracy.

We’ve also seen big changes regarding religion. The share of the American population identifying as Protestant Christians has dropped from about 80% to less than half, while the share of Americans with no affiliation has jumped from negligible to nearly 30%.

Other changes also hit American religion, which can perhaps best be seen in Fosdick’s Baptist tradition. Fosdick’s own denomination, American Baptist Churches USA (then known as Northern Baptists) has remained fairly steady with a membership of 1.4 million in 1925 and 1.3 million today. And while Northern Baptists saw some struggles and losses due to the Fundamentalist-Modernist conflict, Baptists south of the Mason-Dixon more clearly proved Fosdick’s concerns.

The movement launched in 1979 to shift the Southern Baptist Convention rightward — what many call a “fundamentalist takeover” — was built on issues like inerrancy that Fosdick specifically critiqued in his sermon. The fundamentalist effort to draw these narrower doctrinal lines and drive out anyone else as a “liberal” proved successful. That is, until the fundamentalist propensity to keep fighting heretics — real or otherwise — flared up again, this time casting out some of the former fundamentalist heroes. After significant growth through the 20th century, Southern Baptists now find their numbers declining for two decades — and yet focus their energies on new fundamentalist fights.

When someone thinks of a Baptist today, the first image probably isn’t a New York intellectual liberal like Fosdick but a fundamentalist southerner like Franklin Graham or Robert Jeffress. The fundamentalists came to dominate not only institutions and ministries but even the brand itself.

Still, as one of us (Brian) wrote last year for Religion & Politics, “The fundamentalists have won time after time, yet they are determined to keep on fighting.” The inherent flaw of fundamentalism is that every victory eventually sparks a new fight among themselves. New dogmatic lines must be policed. New enemies transgress them and must be vanquished.

As several of our commentators noted, fundamentalism has evolved to a place where today’s tests of Christian sincerity involve embracing partisan politics, conspiracies theories, and even White supremacy. Fosdick decried the fundamentalism of his time for its “bitter intolerance,” adding that “fundamentalists have no solution” to big problems facing society.

His warnings proved prescient. They remain relevant. Hopefully, there is still time to influence the answer to his question as the next hundred years unfold.

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor & Beau Underwood

Thank you so very much for a most timely lesson from history. My acquaintance with Fosdick was limited, having never dug into his ministry at a very deep level. I am indebted to you for sharing portions of his sermon. I am going to search for the full text and read it in its entirety. Also, appreciated those who affirm that Fundamentalism is simply White Christian Nationalism, the terms are essentially interchangeable. Keep up your outstanding work.