Review & Giveaway: Accompanying Disability

I’m guilty as charged.

“In theological contexts,” Topher Endress writes in Accompanying Disability: Caretaking, Family, & Faith, “another common narrative is religious leaders just now realizing disabilities are, like, a thing.”

I have been that religious leader. My formal education taught me a lot, but it did not require me to wrestle with this part of the theological conversation. In a lot of ways, the congregational and professional spaces where I’ve spent my time have also overlooked or ignored the perspectives, needs, and gifts of people with disabilities. And, to be clear, I was a leader in those churches and organizations, so the blame for those transgressions lands on my shoulders.

Then, in my current ministry context, wise leaders helped me grasp what I had missed and the harm such ignorance created. They introduced me to new voices and asked our community to wrestle with difficult questions. We are still far from perfect, but we’ve grown in ways that have made us a church that strives to be a place where everyone can participate and belong.

The regret that I carry and the wisdom that I’ve gained have made me an evangelist encouraging pastors — and Christians more broadly — to center the voices of disabled people and giving disability theology the attention it deserves.

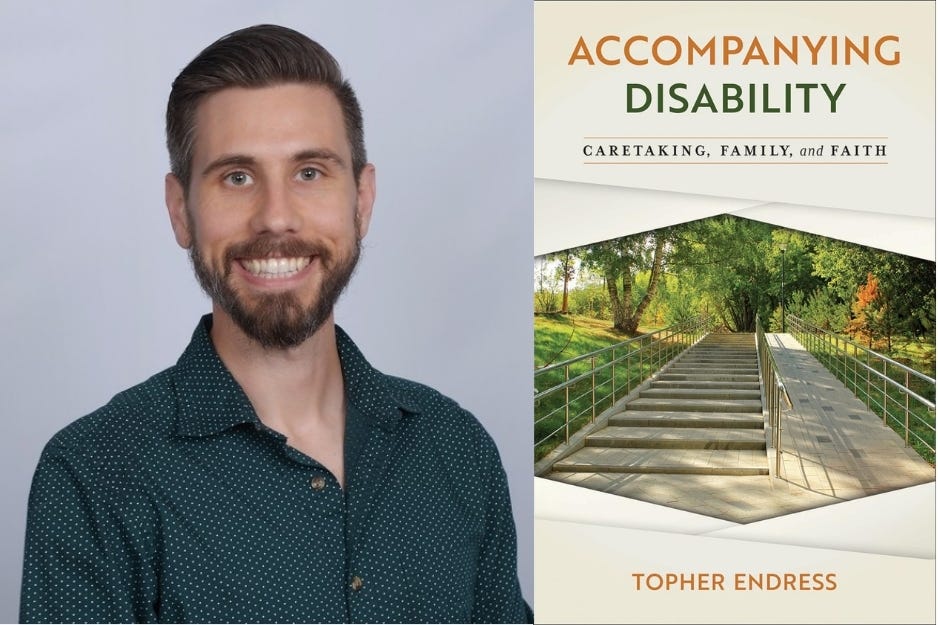

So I was excited to learn about Accompanying Disability’s publication. I enjoyed connections to the church and community that Endress serves. But I wasn’t fully ready for what this book would share with me, because the book itself defies classification.

The book’s a dialogue between father and son with memoir-like qualities. It’s rooted in theological reflection and designed to have a practical impact on churches. As if that wasn’t enough, it also seeks to break new ground by introducing the concept of “accompaniment theology,” which focuses on the stories and insights of those in caregiving roles.

Endress is clear that his attempt to add this perspective is not meant to crowd out other voices. Instead it complements and expands the conversation.

“Disability and accompanying disability are not the same experience, but the work each uncovers is universally useful to the church and to those whose lives are shaped by disability,” he explains. “My hope is that by carving out clear space for those of us who experience caregiving, we can open even more space concurrently for disabled voices to have their own dedicated platform, making that much more clear the ways God is moving among us all in particular ways.”

For Endress, this exercise was not just academic. The project is informed by his own experience as a caregiver for his father, who went “from an energetic, surprisingly fit man of a certain age to a man who used an electric wheelchair, controlled by sensors placed in a half-halo around his head.” That transition occurred on a hike shared by the father and son, transforming each of their lives and the life they shared together.

The perspective offered by the book is not Endress’s alone. The words of his dad, John, are also front and center.

“It is difficult to put into words what I felt during this near-death experience,” John says about the accident. “It was a purely emotional experience. The best way I can explain it is to say that I was in a great mood. I think we all struggle with varying in our beliefs about an afterlife, and my euphoria came about because I intrinsically felt that an afterlife did indeed exist, even though I didn’t necessarily feel like I was heading there anytime soon.”

Despite finding hope in his changed circumstances, John notes how others struggled to respect and appropriately extend care to him. One particular reflection focuses on a nurse that ignored his refusal of a drug. Violating his autonomy, the nurse “proceeded to slip it in with my nightly medications. It was only after the side effects became apparent that I realized what she had done. Once again, because I was unable to speak, I could not address the issue directly.”

Those two contrasting vignettes indicate the power and depth this book offers as a source of understanding and reflection for individuals and churches. It’s a great entry point for those wanting to engage conversations around disability, caregiving, and Christian faith.

“Disabled Christians are not distinct from able-bodied Christians when it comes to anyone’s capacity for holiness, faithfulness, love, and grace,” Endress rightly notes. “And the ways that accompanists are formed and re-formed by the journeys of those they love pulse with the same energy that God offers to us.”

Accompanying Disability helps us to grasp the diversity of bodies that are within the Body of Christ, and the variety of stories those bodies can tell us about God and the world we share together. We’ll be sending a copy of the book to one lucky paid subscriber of A Public Witness. So if you’re still on our free list, make sure to upgrade today.

As a public witness,

Beau Underwood