Review & Giveaway: Corpse Care

Calling your attention to a book about dead bodies feels a little strange this close to Easter. Having just celebrated an empty tomb, focusing on the care of dead bodies seems liturgically off-message.

Yet, what happens with Jesus’s body is central to the resurrection story. One of his followers shrouded his body with linen cloth (Luke 23:53). The women who discovered that Jesus had risen went to the tomb to anoint his body (Luke 24:1). The neatly discarded wrappings proved a sign of the miracle that occurred (John 20:7). These burial customs are significant elements in the divine drama.

Just as the crucifixion presented Jesus’s disciples with a conundrum, the issue of death confronts Christians and their communities today. Human life inevitably ends in death. Our animated bodies eventually become corpses.

As Union Theological Seminary philosopher Cornel West said, “We’re beings toward death, we’re featherless, two-legged, linguistically-conscious creatures born between urine and feces whose body will one day be the culinary delight of terrestrial worms. That’s us.”

Christians and others engage in metaphysical speculation and argument about what happens after our deaths. But what about the corpse?

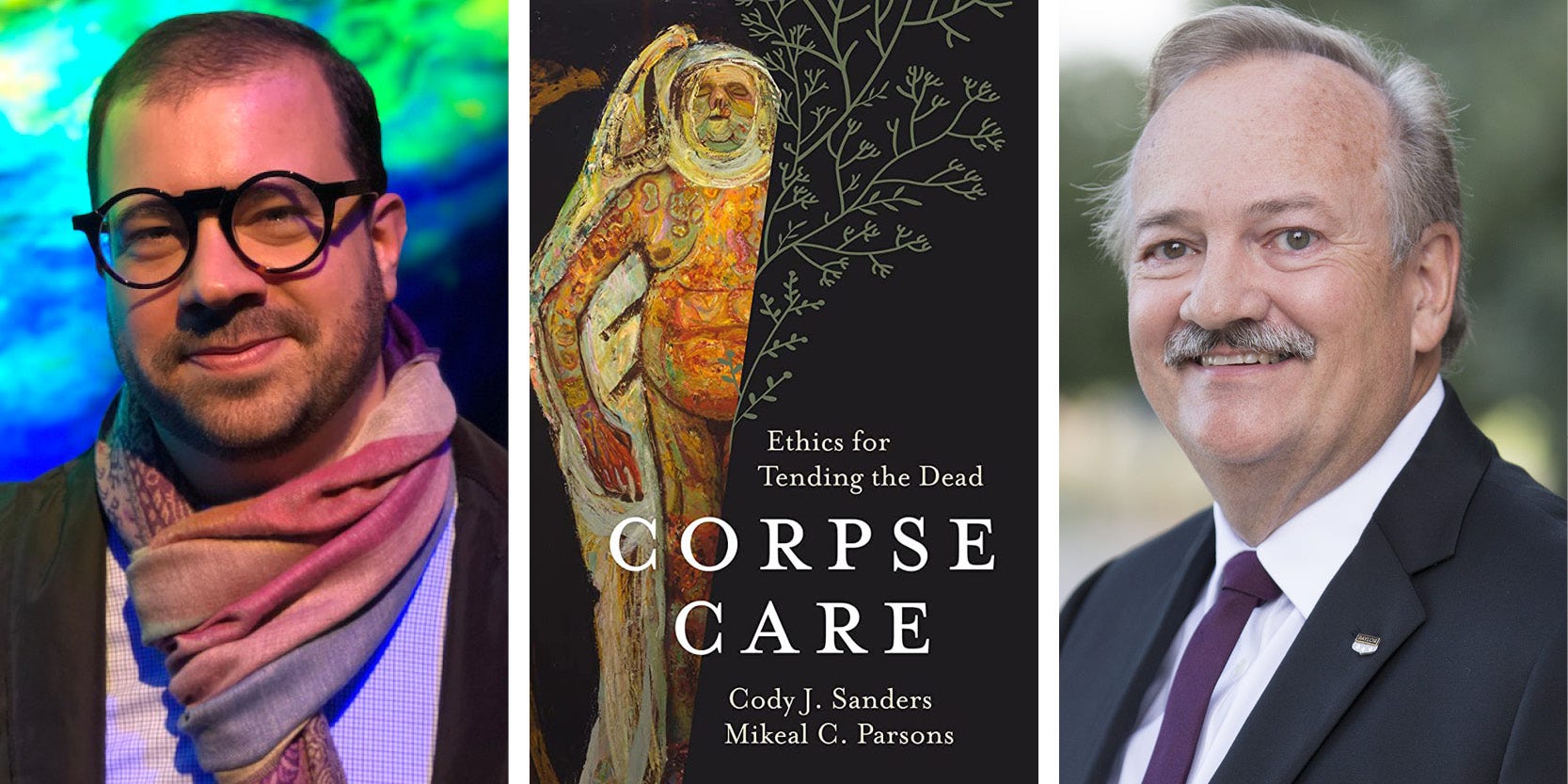

“What [Christians] do in relation to our dead bodies is a subject that we do not often discuss in a theological way in our circle of friends, with our family, or within our congregations,” Cody Sanders and Mikeal Parsons wrote in Corpse Care: Ethics for Tending the Dead (Fortress, 2023).

Their book attempts to spark new conversations that reclaim responsibility for faith communities from the funeral directors and other deathcare providers that professionally process our corpses without much reflection on their meaning.

The first part of the book focuses on the history of the corpse. While the brevity of the book and the vastness of the topic requires their treatment to be episodic, the picture they paint is not a pretty one (and that’s not just because dead bodies rot quickly).

At various moments in time corpses have been used as symbols of violence and social control, with the lynching and mutilation of Black bodies in the U.S. a prime example. Responding to the realities of wars and mass casualties requires violations of funerary customs that dehumanize the living and dishonor the dead. From the days of the Puritans to the present, controversies surround the high costs of funerals and the reduction of death to another economic event in the life of a (now dead) person.

This sordid and morbid history suggests a reconsideration of how we care for the dead. Sanders and Parsons root their reflection in the human and Christian connection to the soil. Both biblically and ecologically, human bodies enjoy a profound relationship with dirt. Natural burials, human composting, and water cremation are all emerging practices that make the most of this connection. They offer different paths for treating corpses in ways more authentic and more theologically appropriate than modern funerary customs.

The authors also encourage Christians and faith communities to revisit their role in caring for the dead. Both home and church-led funerals provide avenues for reducing or even eliminating the role of the funeral home industry — and the attendant expenses — in remembering those who have departed from our lives and community.

Indeed, I recently began a new ministry as a pastor of a church in Indianapolis. I learned that many of my members have plans to utilize the services of a local cremation society. The costs are much, much lower relative to the services and trappings of a funeral home. Our congregation then handles all the service planning and arrangements, saving families thousands of dollars and affording our community the privilege of tending to the remains of those who have transitioned from this life into the next.

Overall, Corpse Care makes an important contribution to a cultural and theological conversation about deathcare. We need more voices stirring discussion about such weighty topics.

Unfortunately, our desire to keep death out of sight and out of mind limits our appetite (and, presumably, the marketable audience) for such books. Having found Thomas Long’s Accompany Them With Singing: The Christian Funeral an indispensable resource in thinking as a Christian about how we acknowledge death, I’m grateful for another resource that approaches this topic with the goal of faithfully tending the dead.

You can learn even more about the book by listening to Brian Kaylor’s Dangerous Dogma podcast conversation with both Sanders and Parsons.

I realize that many of you may be dying to read this book. This month, there’s something extra special we can offer readers of this review. Both authors have agreed to sign a book, which means we can give away two free copies of Corpse Care each autographed by one of its authors.

Every paid subscriber of A Public Witness is eligible for the drawing, so support our ministry by upgrading your subscription today and you might end up with a new book for your library. It will surely provoke a conversation with anyone who notices it sitting on your coffee table, which is exactly the authors’ intention.

As a public witness,

Beau Underwood