Review & Giveaway: Rebels, Despots, & Saints

Faced with the fierce urgency of now, looking back at the past might appear to be a luxury. Reflecting on what has been can seem like an indulgence when there’s so much requiring our attention in the present. Yet, there’s wisdom — and even power — to be gained from retrospectives that can inform our contemporary pursuits of justice.

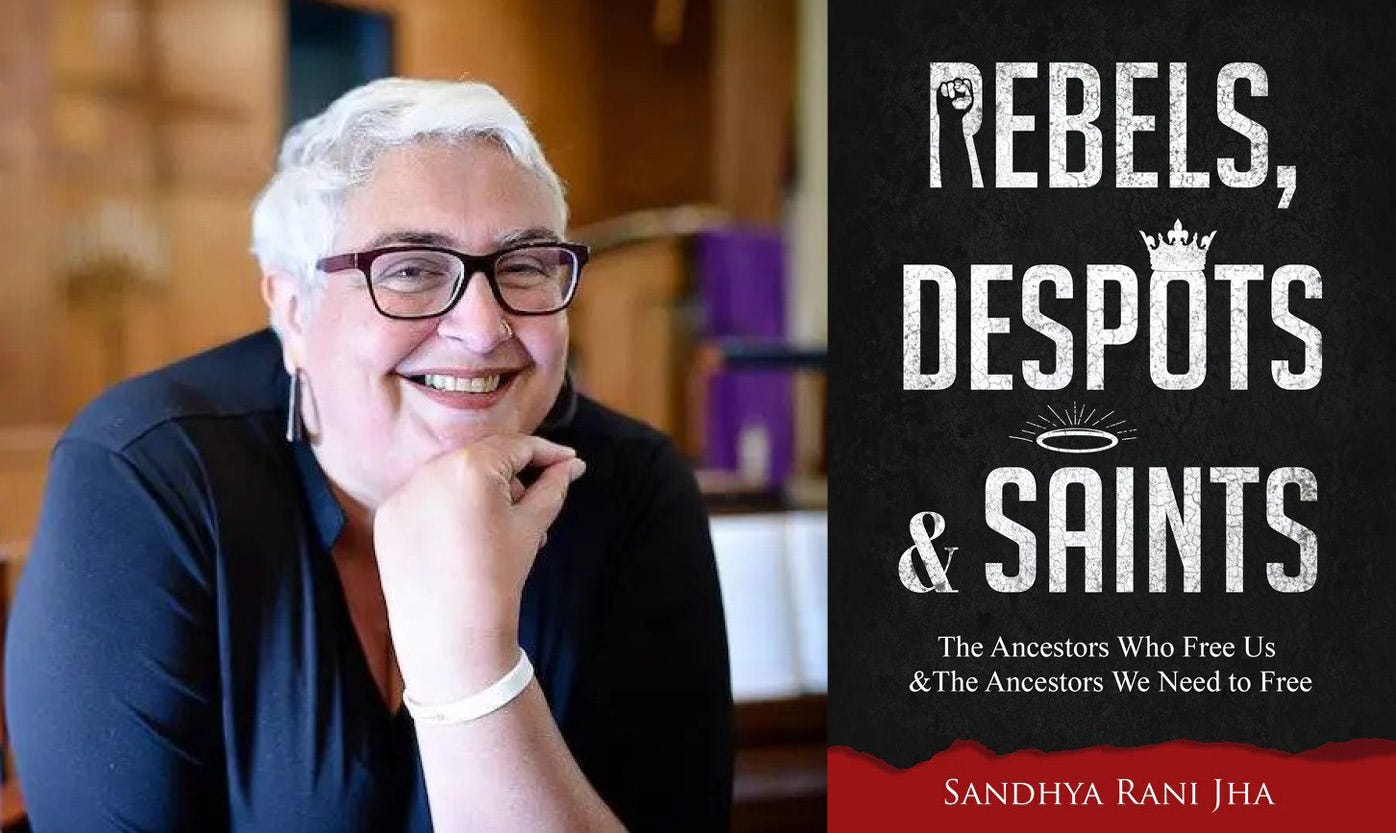

That’s what motivated Sandhya Rani Jha, a peace activist, community organizer, and Disciples of Christ pastor, to write Rebels, Despots, & Saints: The Ancestors Who Free Us & The Ancestors We Need to Free (Chalice Press, 2023). I should also note that Jha is a clergy colleague and a personal friend.

“The most urgent justice work I do can’t continue if I’m not — if we’re not — paying more attention to the wisdom of our ancestors,” Jha explained in the book. “I think the ancestors offer us gifts to engage this moment, and we have more ancestors from whom to learn than we realize.”

Here “ancestors” is a broad term encompassing all those who came before us and still exert influence over us. They may include cultural and spiritual forebears, those who led social movements that we have joined, and even “landscape ancestors” that originally lived on the land we now occupy and can teach us important things about place and some of our false illusions of progress.

These ancestors tell stories, or have stories told about them. There are the well-known tales that dominate the often repeated conventional narratives. Lurking and hidden in the background are other accounts of inflicted harms suffered by those who bore the brunt of such “stock stories.” Stories of resistance describe how previous generations fought against uninvited and unjust forces. And there are unfolding narratives in the present that draw on and continue the unfinished work of the past.

A wide cast of characters operate within these stories. Our “romanticized ancestors” may prove less heroic and virtuous the more we learn about them. In contrast, our “overlooked ancestors” made critical but unheralded contributions in the effort to ensure right trumped might. And, lamentably, there are “atrocious ancestors” whose complicity with wrongdoing, injustice, or even evil must be acknowledged if we are to ever move forward.

“Part of the work of social justice, of telling and living transformative stories, is becoming a community that can validate and support others who may be descended from a line of ‘atrocious ancestors,’” Jha wrote. “In fact, we have to confront the horrors our ancestors wrought, and we are far more likely to do so in productive ways with the help of those around us.”

This is not for the purpose of whitewashing or even attempting to redeem the past. It’s also about more than just learning from it, though awful moments often reveal powerful insights. For example, in these ancestors we can realize the human capacity for evil or see the ways some find themselves in situations defined only by bad choices.

The broader goal is to face the complicated realities that shape what’s transpiring today, whether we like it or not. The naming of such skeletons in our proverbial closet allows us, as Jha explained, to “confront and hold our ancestors accountable, and … seek a way to be accountable to those they harmed.” We reckon with the past, at least partially, to inform and aid our efforts at providing redress in the present.

In Jha’s book, you’ll discover a valuable resource for mapping all this out in whatever space you find yourself, whether it’s wrestling with a congregation whose ghosts frustratingly remain on its membership roles or you’re trying to figure out how your individual story connects to the larger story of a social movement that inspires you. The book provides a different lens for understanding how communities operate and power is utilized within them.

Rebels, Despots, and Saints provides a useful corrective to those talking about the work of social justice in the abstract. Despite motivations to make the world a better place, many who nobly undertake such efforts are quick to ignore the actual messiness of humanity. Jha encourages us to go about this work in a different way by pushing us to attend to the complexities of our histories and become more aware of our interconnectedness with those both living and dead.

Through insightful analysis, well-conveyed illustrations, and eclectic spiritual practices, Jha encourages the reader to commune with one’s ancestors in a way that promotes personal discovery, fosters authenticity, and increases vocational sustainability. The dive into ancestral relations suggested by the book is meant to be both practically useful and spiritually edifying.

Like we do every month, we’ll be giving away a signed copy of Rebels, Despots, and Saints to a paid subscriber of A Public Witness. So if you’ve been thinking about upgrading to a paid subscription and helping support our journalism ministry, now is a great time to take that step. We’ll select that lucky winner later this week.

As a public witness,

Beau Underwood

Oh and if you want to hear an interview with Sandhya Rani Jha about an earlier book, Liberating Love, check out Brian Kaylor’s 2021 conversation with Jha on Dangerous Dogma.

Thank you, Beau, for this helpful review. Too often we underestimate the power of remembering the good and the bad.