Review & Giveaway: Spiritual Care

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, our collective attention rightly focused on the doctors, nurses, and other medical staff who risked their own lives to help others. Less noticed was the work of hospital chaplains, who often provided spiritual care to the dying and served as a conduit between isolated patients and the families from whom they were disconnected.

“My role is to be a bridge between the family and the patient,” Rev. Chris Ponnett, a hospital chaplain in California, explained in 2020. “I want to capture as much of what is happening in the room as possible, to report to the family. Did their loved one say any last words, did they mouth the ‘Our Father’ prayer or respond by grabbing my hand?”

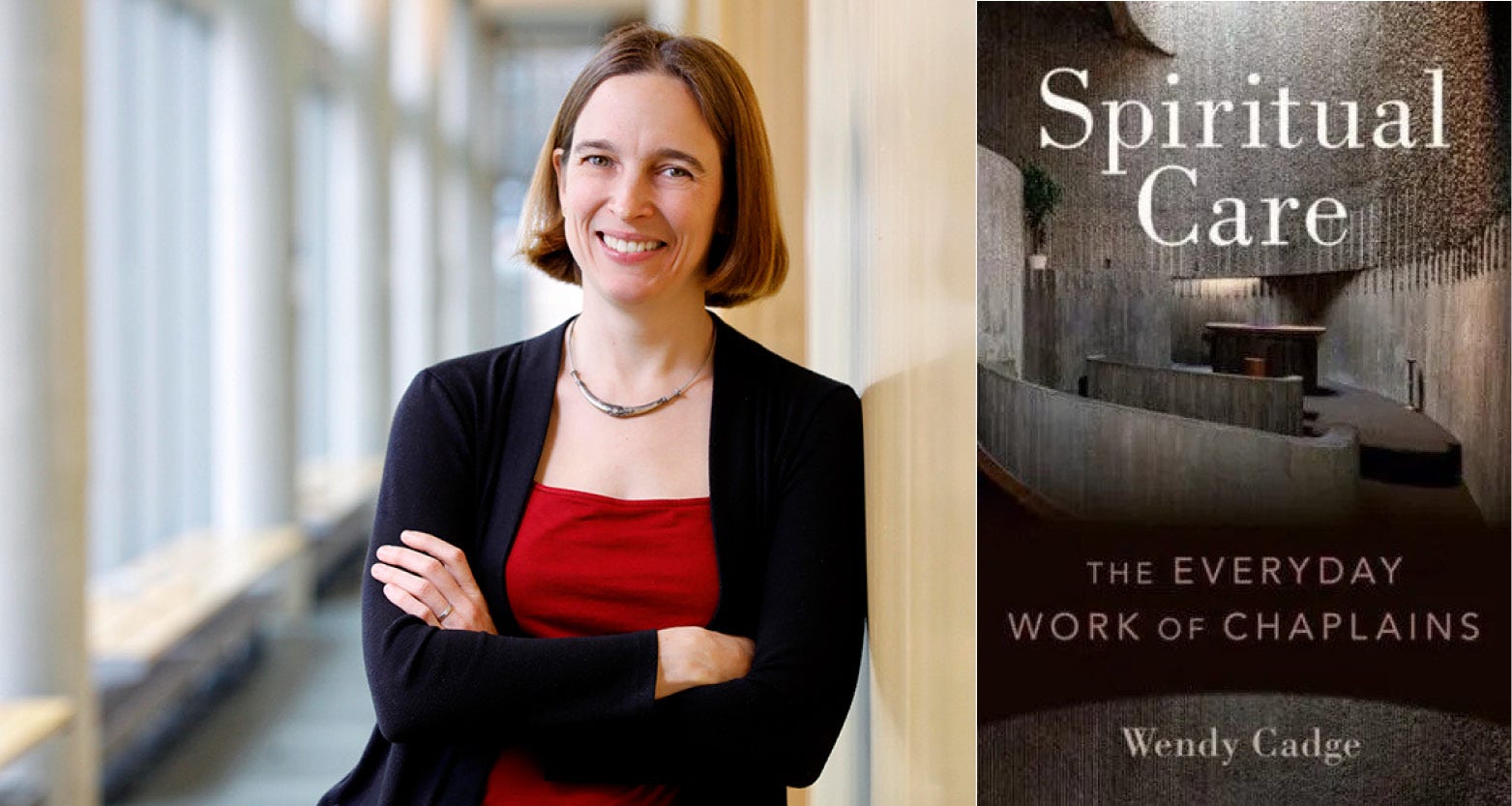

The relative inattention to the efforts of hospital chaplains in our healthcare system is one indicator of a much larger oversight. The role and work of chaplains is often misunderstood or overlooked. Wendy Cadge, a sociologist at Brandeis University and founder of the Chaplaincy Innovation Lab, is out to change that.

Following the release last year of Chaplaincy and Spiritual Care in the Twenty-First Century, a volume she co-edited that aims to provide an overview of chaplaincy, Cadge recently published Spiritual Care: The Everyday Work of Chaplains. Using the greater Boston area as a case study, she interviewed and observed dozens of chaplains at work in contexts that ranged from college campuses to hospital rooms to sea ports. The result is an in-depth study that fills a gaping hole in understanding how religious care is provided within the United States.

Even the conceptualization of the project proved difficult, as the world chaplain denotes a wide range of roles.

“Chaplains range from volunteers with limited formal training in religion to highly trained professionals with multiple degrees,” she wrote. “In some settings, like the military, there is more homogeneity in who uses the term, while in others, like social movement organizations, there is not.”

Her inductive approach — researching who self-describes their work as chaplaincy within a particular geographical area and then setting out to interview them — leads to a nuanced picture of how spiritual care is provided by those who claim this title. While the roles are diverse, Cadge identifies several commonalities: the particulars of their role are shaped by the institutional structures in which they work, they provide a compassionate and empathetic presence to those under their care, they engage the realities of death and existential meaning, and they are often required to navigate and mediate religious differences.

Beyond the descriptions and findings, she unearths a larger story. As fewer people in the U.S. participate in organized religious communities, the work of chaplains becomes more pronounced. Whereas common tradition and pastoral relationship undergirded spiritual care in the past, increasingly it is setting and circumstance that defines its context today.

“[Chaplains’] clients are persons with whom they are temporarily brought together for other reasons — reasons such as war, sickness, crime, employment, education, or disaster — persons who may be of any religious affiliation or none. These professional encounters are spread across the secular landscape of contemporary life,” wrote Winnifred Fallers Sullivan in her own study on chaplains, A Ministry of Presence, where she aptly labeled chaplains, “a priest of the secular.”

In this sense, the evolving work of chaplains and the growing prominence of their ministries are indicators of broader trends in American religious life. Cadge’s exploration of who chaplains are, what they do, and how the settings in which they operate exert influence over their efforts also provides insight into how spiritual practices are evolving and the, perhaps, unexpected places where religion shows up outside of spaces traditionally marked off as sacred.

While Cadge’s volume makes an important contribution to a neglected area of conversation and study, she readily acknowledges how much ground remains untrodden in this area. Her study is simultaneously the generation of new knowledge and a clarion call for others to join her in further examining the work of chaplains as they move from the margins to places far closer to the center of the religious landscape.

“I hope this book will lead scholars and members of the public to see the in-between places chaplains identify and where chaplains dwell. I hope this book encourages scholars of religion to look for the chaplains around the edges and consider who the people are who that use the term and concept,” she wrote. “The liminal nature of the work chaplains do challenges the neat institutional definitions we use to divide work in today’s institutions.”

In shining the spotlight on chaplains and chaplaincy, Cadge helpfully complicates our understanding of the spiritual care terrain. Chaplains reading her work will feel seen and valued by the attention. The rest of us will better grasp how American religious practice is changing and the diverse but critical ways chaplains serve those whose paths bring them under their care. She talked even more about the important work of chaplains last year on our podcast Dangerous Dogma.

Cadge has generously agreed to provide a signed copy of Spiritual Care: The Everyday Work of Chaplains to a paid subscriber of A Public Witness. Upgrade today so that you’ll be eligible for that drawing and help sustain our journalism.

As a public witness,

Beau Underwood