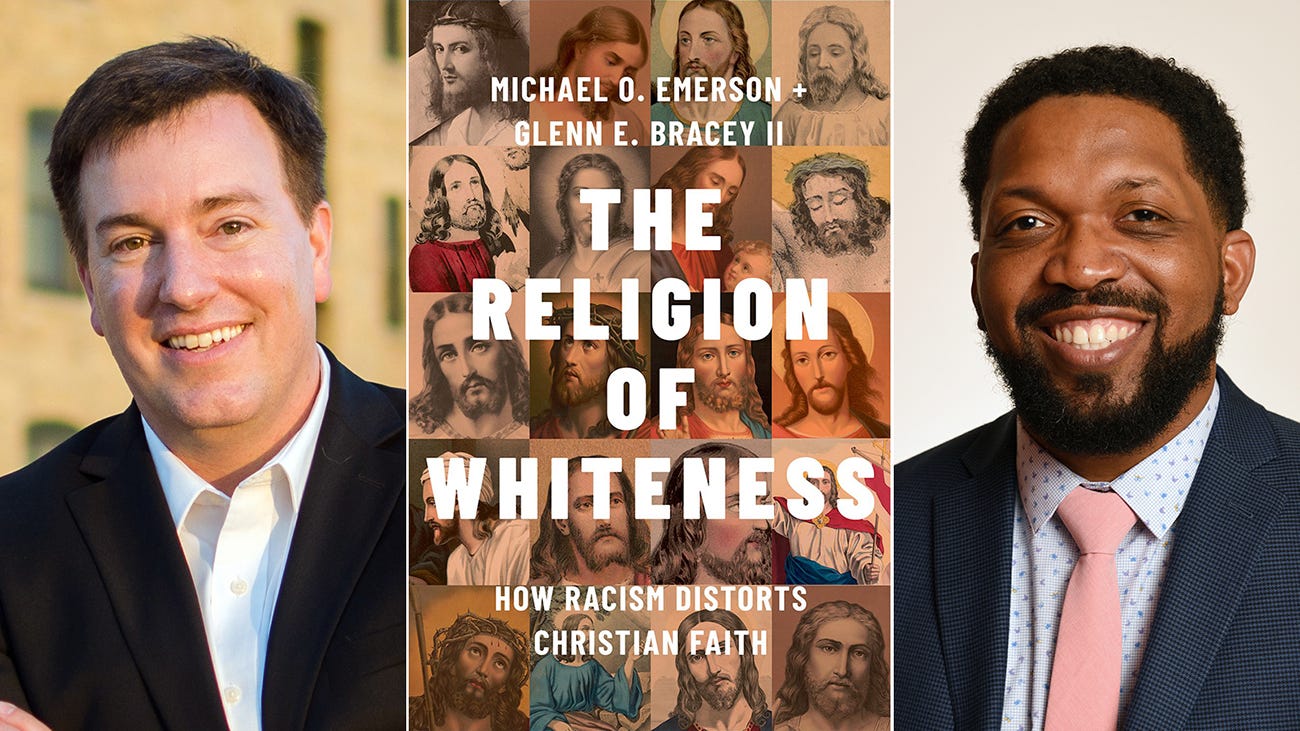

Review & Giveaway: The Religion of Whiteness

There’s a new solution to the old riddle, “If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?” The answer is: Most certainly yes, if that felled tree is then turned into the paper used to print a book called The Religion of Whiteness: How Racism Distorts the Christian Faith. Such a provocative book is destined to generate lots of loud arguments and affirmations because of what is written on its pages.

In this new volume, sociologists Michael Emerson and Glenn Bracey explore another enduring conundrum: Given all the energy and attention Christians and churches have devoted to racism and racial injustice, why do these problems linger in our faith communities and in broader public life?

Their answer is searing and searching. Rather than pursuing justice and reconciliation, many American Christians are committed to being part of the problem. These societal ills are “the life-giving force of a dominant group’s religion. Put simply, we cannot understand racial injustice without understanding the religion that feeds on racial injustice.”

Emerson and Bracey label this faith “the Religion of Whiteness,” defining it as “a unified system of beliefs and practices that venerates and sacralizes Whiteness while declaring profane all things not associated with Whiteness.” The adherents of this tradition are worshiping and perpetuating the dominance of White people in terms of power, privilege, and other resources.

Employing the language of Emile Durkheim, Emerson and Bracey assert that this race-defining religion provides participants with an experience of “collective effervescence.” They gather to enjoy a shared euphoria rooted in the celebration of their own perceived normative status and racial superiority.”

In the book, they unpack “the Religion of Whiteness” as having all the common marks of a faith group: beliefs (White supremacy and its related tenets), practices (selective use of Scripture reinforcing beliefs, deliberate ignorance around issues of race and racial inequality, the veneration of sacred symbols [e.g. a White Jesus, Confederate flags], protecting Whiteness, and opposing non-White Christians who push back against this established racial hierarchy), and social organizations (churches and parachurch organizations that operate according to these beliefs and undertake these practices).

Of course, the authors acknowledge that “no one goes around saying that they believe in the Religion of Whiteness. There is no Church of Whiteness that people attend on Sundays.” To test their theory, Emerson and Bracy conducted their own surveys and focus groups — along with drawing on existing data and research — to provide statistical support to validate their claims. Those wanting to doubt their findings or cast aspersions on their findings will have to wrestle with the evidence they marshall.

It’s also helpful to think about the distinctions among American Christians that the authors draw from their data. Within those categorized as belonging to “the Religion of Whiteness” (about two-thirds of White American Christians), Emerson and Bracey identify about 75% of people falling into the “White veil” camp where they struggle to see racial inequality and thus refuse to see the ways they perpetuate historical and structural inequities within church and society. The other 25% they label as “White might” are more overt in naming Whites as the victimized group with legitimate grievances to be heard and redressed. Both represent an ugly side of American Christianity, though in quite different ways.

Still, based on their survey data there’s a third of practicing White American Christians who fall outside these two groups, who are deemed “the remnant.” In defying “the Religion of Whiteness,” this group also has stories of ostracism and betrayal by those who claim Christianity but are actually worshiping Whiteness. Herein lies both the problem and the hope.

The tragic reality is that part of the harm experienced by many non-White Christians comes not only from the lived realities of racial injustices but the refusal of Christians and churches to respond in ways that reflect their professed values. This is named as an example of the psychological concept called “betrayal trauma” that stems from “when people or institutions on which a person depends significantly violate that person’s trust or well-being.” The hypocrisy of White Christians inflicts additional pain on those already suffering from racism’s firm grip on society.

The potential that exists is for “the Religion of Whiteness” to be confronted by all those — presumably both non-White Christians and those who constitute “the remnant” — who resist it with an alternative.

“Hope lies in the possibility that the [the resisters] will tell a new, united counterstory filled with heroics, drama, hope, and change. [The resisters] will tell the story of staying true to their values no matter the consequences,” the authors write. “They will tell the story of people somehow, someway, overcoming the odds and overcoming evil.”

Depending on your perspective, this is a book that reveals what you’ve suspected to be true or challenges cherished assumptions about the ideals and motivations of American Christians. Either way, it deserves your engagement. We’re grateful that Emerson and Bracey have offered three signed copies (autographed by both authors) of The Religion of Whiteness to be given away to paid subscribers of A Public Witness. So upgrade right away if you’re not already a paid supporter of this ministry to ensure you’ll be eligible for the drawing.

As a public witness,

Beau Underwood