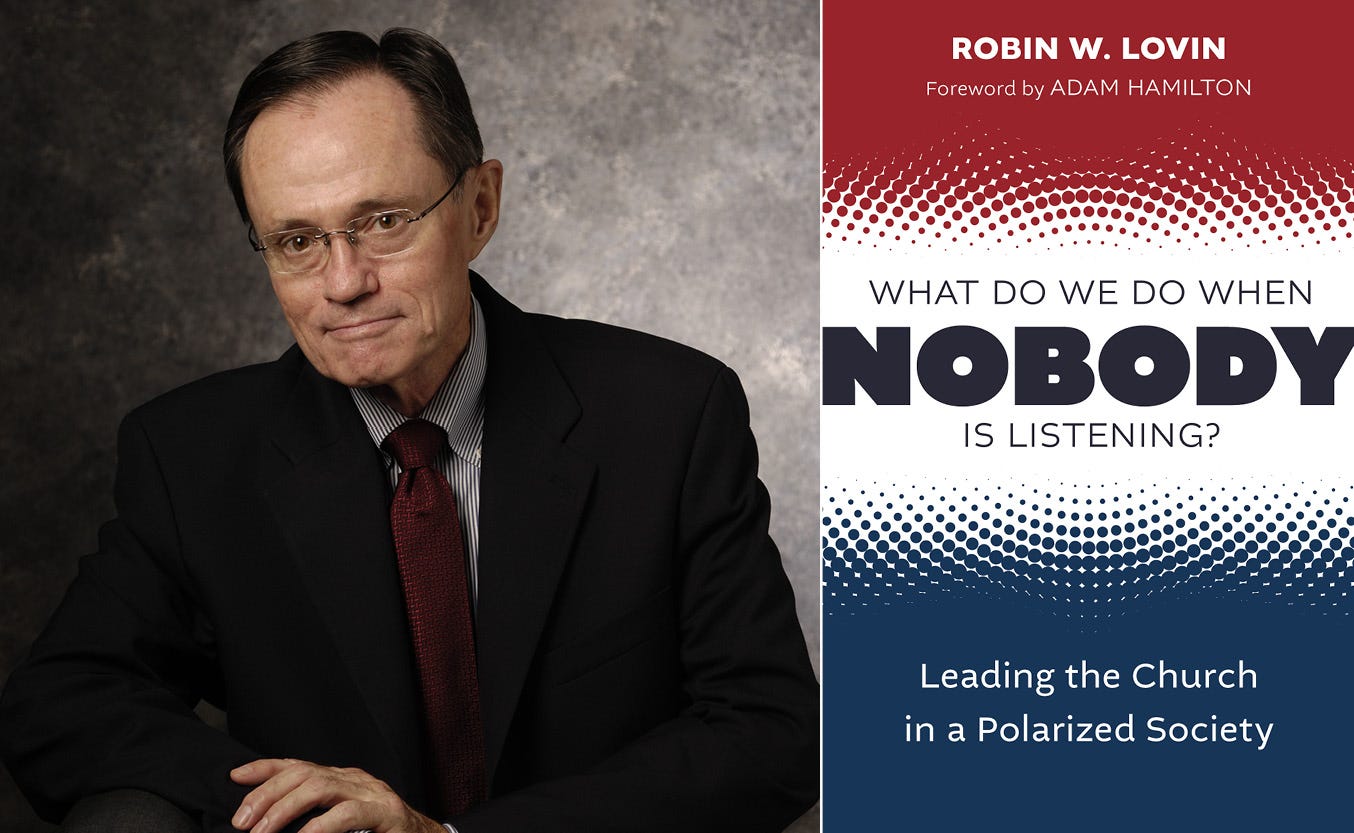

Review & Giveaway: What Do We Do When Nobody is Listening?

“Open your ears!”

Like a parent scolding an inattentive child, Christian ethicist Robin Lovin has a message for a culture — and those seeking to change it — that refuses to hear voices attempting to correct, challenge, or teach. While kids eventually become less distracted or obstinate, it remains to be seen whether wise guides like Lovin can refocus our communal conversations. What’s inspiring is his conviction about the role that Christians and the Church can play in this moment.

Lovin’s What Do We Do When Nobody is Listening: Leading the Church in a Polarized Society joins a growing number of important books warning of the threat tribalism poses to democratic society. Our tendency to sort into warring camps that assume the best about ourselves and the worst about others undermines a system of self-government based on the equal status of participants, public debate, and shared norms. We exist in a time when many cynically use the privileges of democracy for selfish or even authoritarian ends.

I earlier reviewed Christopher Beem’s The Seven Democratic Virtues: What You Can Do to Overcome Tribalism and Save, which is intended as a resource for citizens seeking to channel their energies in support of democratic life. Lovin’s volume is a worthy companion for followers of Jesus wanting to faithfully apply their convictions in meeting the pressing demands of this perilous time.

“In a divided society, the church has to offer something more than a Christian version of polarized identities,” Lovin wrote. “To put the matter in Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s terms, the church must ‘take up space’ in a different way.”

Lovin urges Christians to take on a posture of listening that embodies an ethic of humility and respect upon which both democracy and Christianity depend.

“Listening is the way we approach the world when we are not trying to do something we already want to do or tell somebody what we already think,” he explained. “Especially in a divided society, the church’s work of formation is about listening to the word of God in a way that makes it possible for us to listen to one another.”

The book suggests this listening be focused on three key sources: the word, the world, and those who are not heard. The first and second are intimately connected. Listening anew to the word forms Christians in virtuous characteristics that guide and sustain their involvement in public life. Moreover, it offers them a clear perspective on the way politics can become a false idol, thus helping ensure non-ultimate things remain in their proper place.

However, Lovin’s call is not to denigrate or dismiss the world. By appropriately contextualizing politics, Christians can appreciate what it rightly offers. It provides opportunities for the pursuit of penultimate goods that contribute to human flourishing, allow us to fulfill our responsibilities to each other, and create a sense of connectedness and community. The world has something to tell us, provided we can appreciate the world for what it is and for what it is not.

Finally, Lovin emphasizes the need to expand who is involved in the conversation by listening to ignored and marginalized voices. He rightly points out that the neglect of these voices is often caused by social structures that create barriers to participation for many and protect those already benefiting from the status quo. The Church can address this by rebuilding the nation’s social capital, including those society forgets but Jesus attends to, and modeling a more inclusive way of structuring shared life.

There’s a tragic element to this book. Many who read it may initially resist its ideas precisely because they are polarized participants in our current politics. While Lovin writes to those alienated by this dynamic, it is the engaged and not the apathetic who are likely to be attracted by the topic. Those overly confident of their own righteousness would be smart to recognize their own trouble listening and see the opportunity this book represents to engage with an astute observer of how faith intersects with public life.

The reader will quickly see the audaciousness of Lovin’s project. This relatively brief book calls Christians to a rather different way of involving themselves in politics than is practiced by contemporary partisans. He tackles this complicated dynamic by drawing upon resources from Christian theology and political theory. He seeks to present these ideas to a general audience in a way that will be edifying to Christian communities, many of whom are vexed by the tribalism eroding our democracy but at a loss for how to respond.

Let anyone with ears listen!

As a public witness,

Beau Underwood

By the way, we’re giving away an autographed copy of Lovin’s book to a paid subscriber of A Public Witness. We’ll select that winner at the end of this week. So if you’re not already a paid subscriber, upgrade today for your chance to receive a signed copy of What Do We Do When Nobody is Listening. You can also learn more about the book by listening to Brian Kaylor’s interview with Robin Lovin on our Dangerous Dogma podcast.

Loving is spot on, but the truth is, society has paid attention to organized Christian religion. Whether established denominations, Methodist and Presbyterian for example, or the

Independent evangelical church, that meets in a vacant store front, churches divide and split over things that would bring Christ to tears. And this is not a new trend. Is there a historic denomination that wasn't split over slavery or Earth being the center of the universe. Unfortunately most "christians" are focused on their ideology instead of following Christ. jbl