The Bread, the Cup, & the Politics

One of us grew up in a church where communion was a part of weekly worship. While only baptized adults were allowed to participate during the service, a group of kids would rush downstairs to the kitchen once the final hymn was sung. That was where the leftover communion was placed by the deacons and we would sneakily drink shots of grape juice until our thirst was quenched.

Until we got caught.

It only took a couple weeks of the communion trays being unusually empty for some of the adults (and our parents) to realize what was happening. “It’s just grape juice!” we protested to no avail. This was literally true. What we were drinking was something you could buy at any grocery store, but we still found ourselves scolded for our irreverence.

That’s because the grape juice we imbibed represented something far more significant. We were not just standing in a kitchen enjoying the flavor of Welch’s; that sweet liquid was meant to symbolize Jesus’s horrific death on the cross. It was a reminder of who our lives fundamentally belonged to and a sign of God’s love for us.

For Christians, communion is considered a sacrament. Having acknowledged our own mistakes and transgressions, we come to the Lord’s Table to experience the grace that covers our sins. As John Bosco, a 19th century Catholic priest who was later canonized, explained, “We do not go to Holy Communion because we are good; we go to become good.” This was the meaning the younger version of ourselves failed to grasp. It appears many Catholic bishops are struggling to learn the same lesson today.

In this edition of A Public Witness, we’ll walk you through the theological missteps being made by Catholic leaders attempting to deny communion to President Joe Biden and other politicians over the issue of abortion. And we’ll look at why the politics of communion matter so much to non-Catholics like us.

Biden & the Bishops

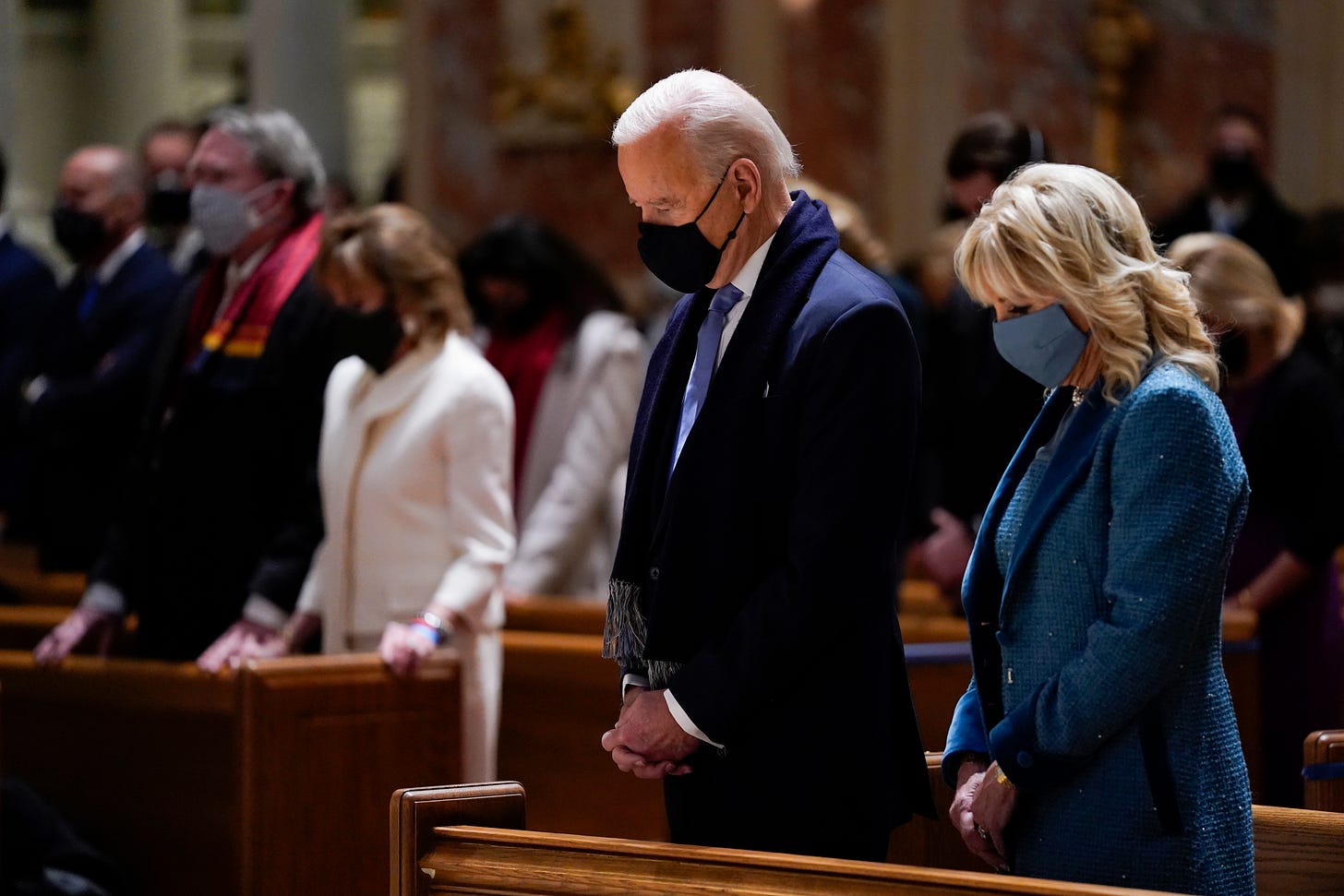

The election of Joe Biden as president would appear to be a moment of exaltation for the U.S. Catholic Church. While he is the second Catholic president in history, he is clearly the most devout one. As Jackie Kennedy noted, her husband was “such a poor Catholic.” The same cannot be said about Biden. Sitting in the Oval Office is a man who attends mass every Sunday, carries a rosary, and openly talks about the impact faith has on his life.

Biden is the epitome of what Catholic leaders desire among their flocks: someone who rigorously practices their faith and respects both the rituals and authority of the church. His steadfastness — even attending mass at a local parish while in England for the G7 Summit — could be called a godsend. Church participation in America is rapidly falling, with the decline being more severe among Catholics than Protestants. Polls reveal declining deference to Catholic teachings and diminished respect for clergy. Given these alarming trends, now would seem the ideal time to celebrate Biden as an example worth emulating.

Furthermore, the president’s agenda closely aligns with Catholic Social Teaching and other tenets taught by his church when it comes to poverty, migration, climate change, the death penalty, and a host of pressing policy issues. The big difference, of course, is over abortion. On that particular one, Biden is not such “a good Catholic.”

This disagreement erupted anew last week when the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops voted to draft a statement on the meaning of the Eucharist that could result in pro-choice politicians, including Biden, being denied communion during mass. In an ironic twist, several of the bishops during the USCCB debate cited the prominence of the president’s faith as the motivation for taking this step.

“We’ve never had a situation like this,” claimed Bishop Liam Cary of Oregon, “where the executive is a Catholic president who is opposed to the teaching of the church.”

The move itself was striking, as leadership in the Vatican cautioned against it and one leader close to Pope Francis explained the concern “is not to use access to the Eucharist as a political weapon.” In fact, Francis himself previously argued “the doors of the sacraments” should not be “closed for simply any reason.” He also added, “The Eucharist, although it is the fullness of sacramental life, is not a prize for the perfect but a powerful medicine and nourishment for the weak.”

The new effort to deny communion to Biden will likely fail, as formal enactment requires either unanimous support among the USCCB or 2/3rd’s approval among the bishops and then sign-off from the Vatican. Even if successful, the guidance would not be binding on diocesan leaders. Cardinal Wilton Gregory of Washington, D.C., previously indicated his reluctance to withhold communion from his most famous parishioner.

These realities have raised questions about the bishops’ true intentions, reported Jason Horowitz in the New York Times: “Opponents of the vote suspect a more naked political motivation, aimed at weakening the president, and a pope many of them disagree with, with a drawn-out debate over a document that is sure to be amplified in the conservative Catholic media and on right-wing cable news programs.”

Politicizing Communion?

These developments have generated criticism of the bishops among some U.S. Catholics.

“Politicizing a sacrament is pastoral malpractice, whether directed against Republicans or Democrats,” Faith in Public Life’s John Gehring wrote before the bishops’ vote, as he noted the partisan double-standard as bishops failed to take similar action against Catholic politicians who enforce the death penalty. “By yoking the fight to end abortion with the crass misuse of a sacrament, U.S. church leaders will only hurt their own credibility, further divide our parishes, and distance themselves from the pastoral leadership of Pope Francis.”

Father Peter Daly, a retired priest, argued that “conservatives in the bishops' conference can justly be called out for playing politics with the ecclesiastical positions.” He added, “We don't want to arbitrate political issues in the Communion line.”

Even some bishops criticized the idea of denying communion to pro-choice politicians. Bishop Francis Malooly, who served as Biden’s bishop in the Diocese of Wilmington, Delaware, until just a couple months ago, previously said, “I do not intend to get drawn into partisan politics nor do I intend to politicize the Eucharist as a way of communicating Catholic Church teaching.”

But what these statements miss is that communion is inherently political. Indeed, one of us wrote a whole book arguing exactly that. Someone taking communion makes a statement that is ripe with politics. In declaring that “Jesus is Lord,” a Christian is announcing that “Caesar is not Lord.” This simple, spiritually-minded but politically-potent exclamation led to the martyrdom of many early followers of Jesus. Rome could not tolerate political insurrection or disloyalty.

“The Christians in the Roman Empire ... recognized that you could not serve the god of the empire and the God of Jesus,” Shane Claiborne and Chris Haw wrote in their book Jesus for President. “This is why they did not choose small language to communicate about Jesus, language such as, ‘It’s just a personal spiritual conviction, not political.’ No, they chose language and imagery with the weight of the empire behind their words.”

Partaking in the Lord’s Supper witnesses to the lordship of Jesus over earthly rulers, pledges our allegiance to the Kingdom of God above our temporal obligations of citizenship, and fosters solidarity with all those belonging to the Body of Christ. Together, we remember the body of Jesus broken on Calvary and, in doing so, together we “re-member” the Body of Christ as unified in our hope of the Resurrecting God. As the saying goes, we — Jesus’s followers — are “what we eat.”

But this re-membering is not limited to those in the church sanctuary with us. Instead, we unite in communion with all who participate in God’s Reign. That means we align ourselves across political parties, beyond national borders, and even across time with the cloud of witnesses from the past, the community of Christians in the present, and the saints yet to come. Tasting the bread of life and drinking from the cup of salvation makes this spiritual reality visible in a way that cannot avoid public implications. As Claiborne and Haw added, “The practice of the Eucharist or communion is a radically political act.”

The problem with the USCCB’s action is that they are disfiguring the political witness of the sacrament by making it a tool serving partisan ends. As we already noted, the same standard has not been applied by the USCCB to other politicians on similar issues. Rather than applying a moral standard consistently across the political spectrum that reflects their tradition’s positions, they are choosing sides at this specific moment in an unprecedented way.

The result is that the sacred politics of communion are subsumed by a partisan agenda. Rather than the communion elements being transubstantiated into the real presence of Christ, the political meaning of the sacrament is reduced to the parochial concerns of the electoral battles waged within a single nation. Partisan communion is not just a different type of communion; it is something else entirely.

Serving the Political Master

The way that partaking in communion transcends the divisions defined by political loyalties and nation-state boundaries is threatening to those invested in such human structures.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, an 18th-century philosopher whose thought influenced the American and French revolutions, argued that religion should be confined by national boundaries for the good of the state. He did not argue for a theocracy, where clergy dictated the positions of the government. Rather, he insisted Christianity should be viewed as merely spiritual, focusing solely on how “to get to heaven.”

If Rousseau could successfully redefine Christianity in this way, then the priests would leave the public square and supreme authority would rest with the state. Thus, he asserted that “Jesus came to set up on earth a spiritual kingdom” resulting in “separating the theological from the political system.” He added, “Christianity as a religion is entirely spiritual, occupied solely with heavenly things; the country of the Christian is not of this world.”

A global faith is dangerous because of the challenge it presents to the state’s demand of allegiance and claims of sovereignty. Rousseau noted the risk posed by clergy who “find their bond of union … in the communion of Churches.” He added, “Communion and ex-communication are the social compact of the clergy, a compact which will always make them masters of peoples and kings. All priests who communicate together are fellow-citizens, even if they come from opposite ends of the earth.” He specifically attacked the Catholic Church as this type of “clearly bad” religion that undermines the ability to create strong nations.

Religion is to be tolerated “so long as their dogmas contain nothing contrary to the duties of citizenship.” Throughout Rousseau’s writings it quickly becomes clear he agrees with Jesus that “no one can serve two masters.” The difference is Rousseau wanted the state to be the master.

Although Catholic theologian William Cavanaugh disagrees with the religious-political philosophies and priorities of modern state philosophers like Rousseau, he credited them with correctly seeing the subversive potential of religious worship: “The Eucharist transgresses national boundaries and redefines who our fellow-citizens are. Rousseau was right to note that communion among churches is a threat to the unity of the state.”

“The new state required unchallenged authority within its borders, and so the domestication of the Church,” Cavanaugh added. “Church leaders became acolytes of the state as the religion of the state replaced that of the Church, or more accurately, the very concept of religion as separable from the Church was invented.”

In this context, whenever clergy speak publicly on moral issues they can be accused of “being political” or “politicizing” the faith precisely because modern Western societies often compartmentalize religion into a private sphere. In these scenarios, faith leaders are perceived to have stepped outside their appropriate place in society in challenging the powers that be. The public square allegedly belongs to the state; religion only deals with matters of the soul. But clergy speaking out publicly is not necessarily any more political than surrendering the public square to the state in the first place.

Yet, an alternative danger exists. If abandoning claims of public witness is to cede control to government rulers, doing their bidding as subservient partisans is problematic in its own extreme way. By taking sides in a U.S. political dispute that puts them at odds with their global leadership, the U.S. Catholic Bishops risk being perceived — rightly or wrongly — as becoming spiritual baptizers of partisan agendas established by secular political actors.

Just as Rousseau hoped church leaders could limit their vision to national borders and thus strengthen the state’s sovereignty, perhaps party leaders wish the same for clergy today. The only thing worse than a nationalistic religion that defines grace by human-drawn borders is a partisan religion that defines salvation within the platform of just one party within one country.

A Better Witness

Nobody is surprised by the position of the USCCB on abortion. The critiques being raised center around the timing of their action and the unequal application of their principles.

“The damage is to the bishops themselves and to the Catholic community they lead,” John McGreevy, a historian at Notre Dame, wrote for Religion & Politics. “Tying the eucharist to abortion means the bishops become another set of political, not moral, actors.”

If we were advising the USCCB (which we’re obviously not, unless they are surreptitiously reading this email), we would offer two suggestions to mitigate this damage and avoid future missteps:

First, rather than drafting a document on the meaning of the Eucharist to create a permission structure for denying communion to elected officials at odds with church doctrine, use this moment to remind themselves and their membership of the sacrament’s true and radical political import. We need more resources for challenging nationalism, idolatry, and granting too much significance to the material realm. Eucharistic understandings and rituals accomplish all these things when properly conceptualized.

This is not a call for the USCCB to abandon their public witness. Rather, it is a suggestion to offer it in a way that transcends partisanship and holds all Catholics in public life to the same standards, while also helping non-Catholics better grasp the teachings of the tradition and the reasons behind them. There should not be politically factionalized “conservative Catholics” and “liberal Catholics” within the institutional church but Catholics who happen to be liberal or conservative.

Second, do not miss the forest for the tree when it comes to the presidency of Joseph Robinette Biden, Jr. We do not presume that all of our readers nor every Catholic voted for this president, nor support every position he holds or action he takes. As committed Christians, we do celebrate the genuine faith he professes and practices. At a time when the Church is threatened by trends of secularization and disengagement, we believe his commitment to humbling himself before God as a human being and private citizen is admirable and inspiring.

Authentic faith is impossible to fake. When found among us, it deserves to be commended instead of attacked. As Pope Francis said, “In the Eucharist, Jesus draws close to us; let us not turn away from those around us.”

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor & Beau Underwood

Growing up in a "closed communion" Baptist church, it took me awhile to figure out that communion should include anyone who chooses to partake of it, rather than be an exclusive kind of religious habit. One of the most moving communions I ever participated in was in London, UK at St. Paul's Cathedral when we were attending the Baptist World Alliance meeting in Birmingham, UK. Although I'm pretty sure the priests giving the wine and bread to participants only intended Church of England members to partake, we were bold enough to get in line with people from all around the world--some in their "native" dress. It was quite meaningful to share that with such a diverse community of believers. Considering the many thoughts we humans have as we participate in something like this--a ritual of faith--I suspect that none of our hearts are pure and far too often we take it for granted without much thought at all. I believe God must smile at us and our attitudes, our condemnation of others and our own lack of worthiness and understanding. May those who allow abortion issues to be a litmus test also see the taking of life for crimes or for hoping to find a new way of life in a country that has always promised so much as distressing as abortion. I pray for this president as his faith urges him to continue to find more humane and just ways to "welcome the stranger."

Your article made me chase a rabbit that I do not understand and probably do not want to catch. What did Paul mean when he wrote about eating this bread and drinking this cup "in an unworthy manner" in I Corinthians 11: 27-32? Is it the naughty boys sipping grape juice in the basement after church or is it trivializing the death of Jesus so that it has no standards? JBC