The Christians Who Matter Most in this Election (Hint: It’s Not White Evangelicals)

During Tuesday night’s debate between Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump, religious references only popped up twice — both by Harris as she talked about abortion bans. She noted that people do “not have to abandon their faith or deeply held beliefs” to support removing the government from the decision process. And she spoke about the trauma of abortion bans on “couples who pray and dream of having a family” but were denied IVF treatments (a concern that arose after an Alabama Supreme Court ruling).

Although Harris was the only one to mention the importance of religion during the debate, such references are unlikely to win over White evangelical voters who generally cite the topic of abortion as justification for voting for Trump despite numerous scandals. But that shouldn’t worry the Harris campaign. Those aren’t the voters she should spend time trying to convince.

Despite the media’s obsession with White evangelicals and whether Harris can win them, that voting block will not be her key to winning in November. New polling proves the Harris campaign — and the media — needs to quit worrying about evangelicals and instead consider other Christians, including those who found themselves nodding their heads with her religious references on the debate stage.

New survey data from Pew Research Center on Monday confirmed that White evangelicals remain solidly for Trump, and it showed Harris enjoying strong support from Black Protestants and Hispanic Catholics. There are also signs in the data pointing to which White Christians will most likely swing the election: White mainline Protestants.

Despite being roughly the same size nationally as evangelicals — and more populous in most of the key swing states — mainline Protestants have been largely ignored in election coverage. Mainliners are also more likely to split between the two parties, putting them more up for grabs than White evangelicals or Black Protestants.

This dearth of attention continues even as mainliners dominate the presidential tickets this year. Harris’s church, Third Baptist Church in San Francisco, is dually aligned with a mainline denomination (American Baptist Churches USA) and a historically Black denomination (National Baptist Convention USA). Her running mate Tim Walz is also part of a mainline denomination (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America), making the Harris-Walz ticket the most mainline pair in two decades. And Trump was a lifelong mainline Protestant until October 2020 when he announced he was “nondenominational” and no longer identified with the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.). The outlier is J.D. Vance, who is Catholic. While Trump’s faith outreach is again led by a Pentecostal minister, for the first time in two decades the role of faith outreach director for the Democratic ticket is being led by a mainline minister instead of an evangelical or Pentecostal strategist.

There’s another nugget in the Pew survey also worth unpacking: the so-called “God gap” that sees people who attend church more frequently then voting in higher numbers for Republicans actually reverses direction among White mainline Protestants. There’s something significant occurring there that sets them apart from White evangelicals and Catholics.

So this issue of A Public Witness unpacks recent polling data and swing state demographics to explore why, despite all the media attention to evangelicals, political salvation for the Harris-Walz campaign will instead be found among mainline Protestants (along with Catholics and the unaffiliated).

Survey Says…

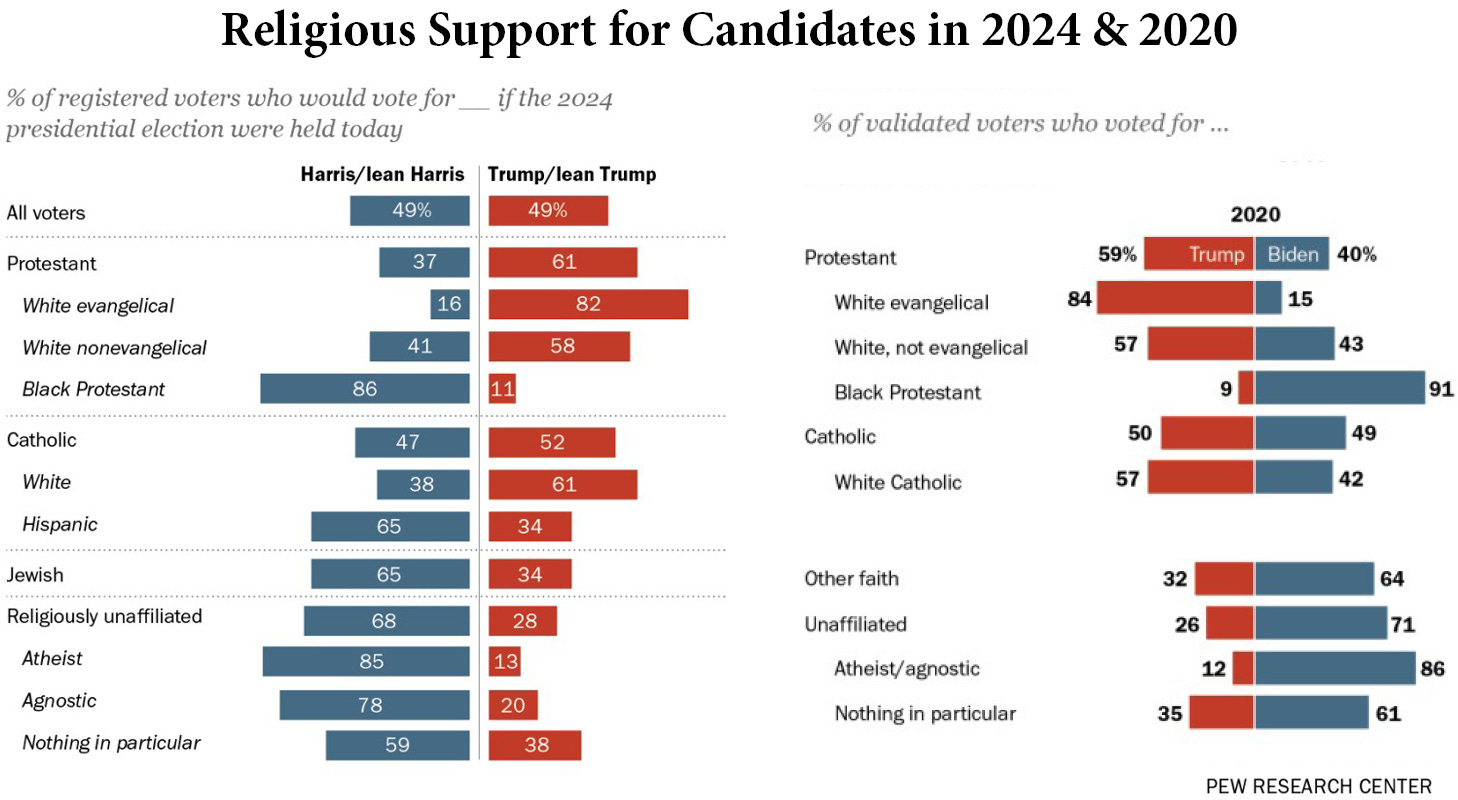

Pew Research Center’s latest polling, conducted Aug. 26-Sept. 2, looked at how members of various religious groups are planning to vote. Overall, they found the nation evenly split between the two candidates, but with various religious demographics mostly lopsided for one of them.

The current poll numbers largely align with the 2020 results (and Pew’s new numbers are similar to ones found last month in a Washington Post-ABC-Ipsos poll). For instance, Trump is crushing it with White evangelicals, 82%-16%. On the opposite side, Black Protestants back Harris 86%-11%. While Catholics overall lean slightly toward Trump (52%-47%), there’s a strong racial divide as White Catholics prefer the former president by 13 percentage points and Hispanic Catholics back Harris by 21 points. Atheists, agnostics, and nones all overwhelmingly support Harris, as do Jewish voters by a 2-1 margin.

The closest religious demographic in Pew’s data is the “White nonevangelical” category (a label they sometimes use instead of mainline Protestant). The group backs Trump by 58%-41%. That’s Harris’s best showing among any White Christian group, and it should offer both hope and concern for her campaign.

When President Joe Biden won in 2020 (and, yes, he did win), he did so by flipping five states and the electoral vote for Omaha, Nebraska. He didn’t need all five states, but what put him in the White House and left Hillary Clinton watching an inauguration from the sideline was his ability to win Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

He managed this electoral turnaround even as he performed worse among White evangelicals (and Black Protestants) than Clinton had in 2016. According to Pew, Trump grew his support among White evangelicals from 77% to 84% while Biden ticked down a point to 15% (there were fewer third-party votes in 2020 so the numbers don’t always move the same). While it’s popularly claimed Trump won 81% of White evangelicals in 2016, that number came from the exit polling that’s considered less accurate than other data that comes out months later. Analyses by Pew, the Cooperative Election Study, and others generally show Trump a few points below 80% in 2016 and a few points above that mark in 2020.

Biden’s pathway to victory, therefore, came from other groups. Over Clinton’s showing, he increased among those of other religions by three percentage points, Catholics five points, unaffiliated (atheists, agnostics, and nones) six points, and mainline Protestants points. Those groups — especially the unaffiliated, mainliners, and Catholics because of their size — made the difference between 2016 and 2020.

While Harris is performing at Biden’s level among White evangelicals, she is running a couple points behind the 2020 results with Catholics, the unaffiliated, Black Protestants, and White mainline Protestants. Compared to Clinton, she is matching among White evangelicals while running behind with Black Protestants and ahead by a few points with Catholics, the unaffiliated, and White mainline Protestants.

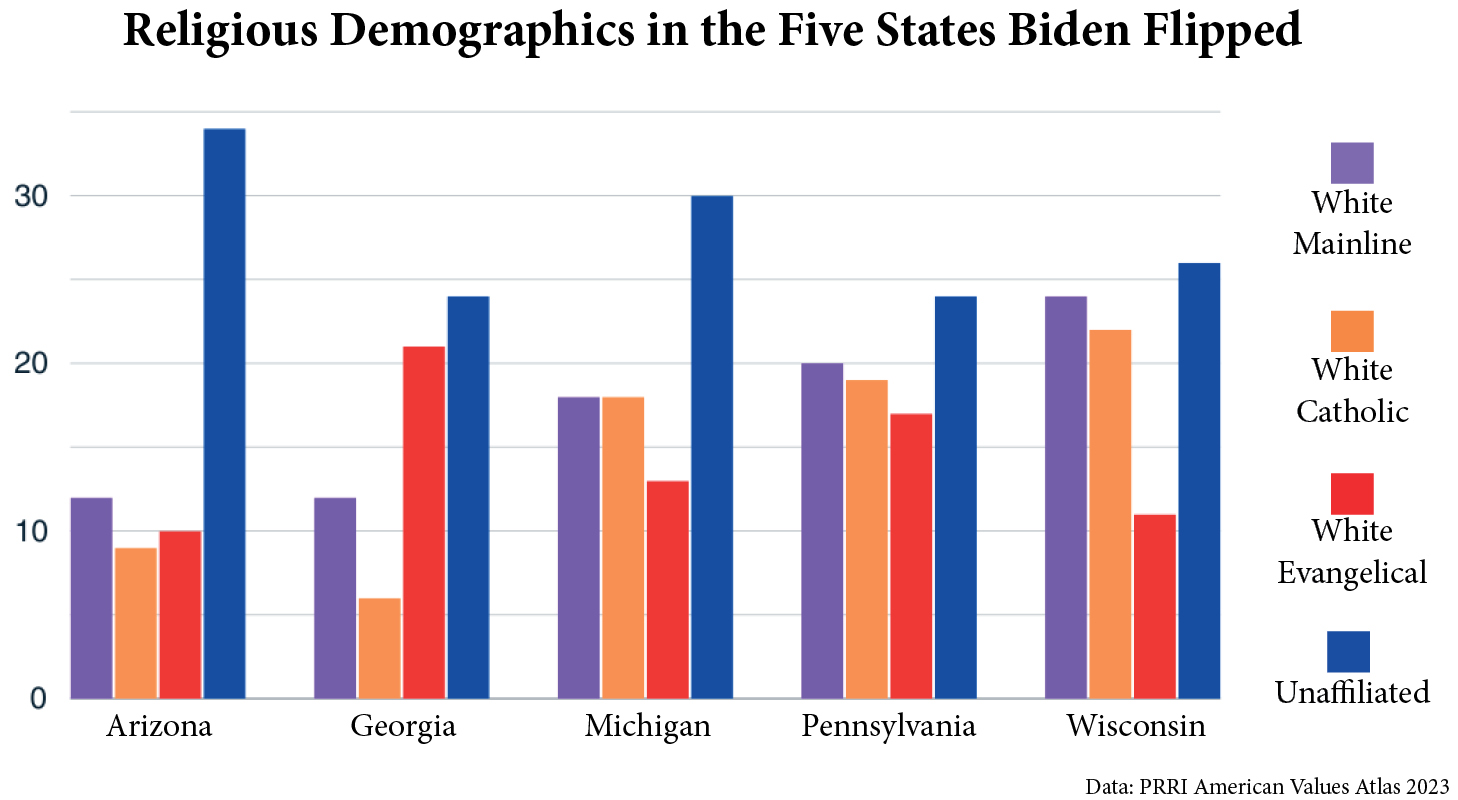

Even though mainline Protestants and evangelicals are about the same size nationally (and White Catholics are just slightly behind), they don’t function the same in the electoral college. PRRI last month released new data showing the 10 most evangelical counties in the country, which are all in states Trump will win, like Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Tennessee. The top mainline Protestant counties include two in Wisconsin while the top White Catholic counties include one in Wisconsin and one in Pennsylvania.

Looking at the five states Biden flipped, the importance of three groups — the unaffiliated, White mainline Protestants, and White Catholics — stand out in the demographics. In all five states, the unaffiliated are the largest religious group. Only in Georgia do White evangelicals come in second. In the other four states, White mainline Protestants are second and in three of them White Catholics also outnumber White evangelicals.

Even if Harris could win another 5% of White evangelicals, it wouldn’t matter much in the electoral college. And it would be quite a lift to increase her support by one-third among a demographic that is clearly committed to her opponent. But winning another 5% of White mainliners or Catholics would not only be easier since she already has close to forty percent among those groups, but it would also have a real impact in the must-win states.

Clearly, focusing on evangelicals in the must-win states of Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin makes little sense. Harris prioritizing outreach to White evangelicals would be as unwise as Trump betting the whole election on wooing Black Protestants. They’re just not that into you.

Yet, each week brings more news reports looking at evangelicals and the question of whether Harris can gain their votes. And some progressive activists also keep devoting their energy to reaching evangelicals in a quest on par with Captain Ahab’s obsession with that white whale. But as historian of American Christianity (and a mainline Protestant) Diana Butler Bass put it, “The strategy never works.”

“Yet, the media is fixated on evangelicals,” she added recently after MSNBC did yet another segment about if Democrats could win evangelicals. “And big-profile moderate and liberal evangelicals get lots of press — and seem to have convinced Democrats that if they can just flip a few evangelical voters, then Democrats win elections. … Trying to flip the evangelical vote is probably a waste of time and money.”

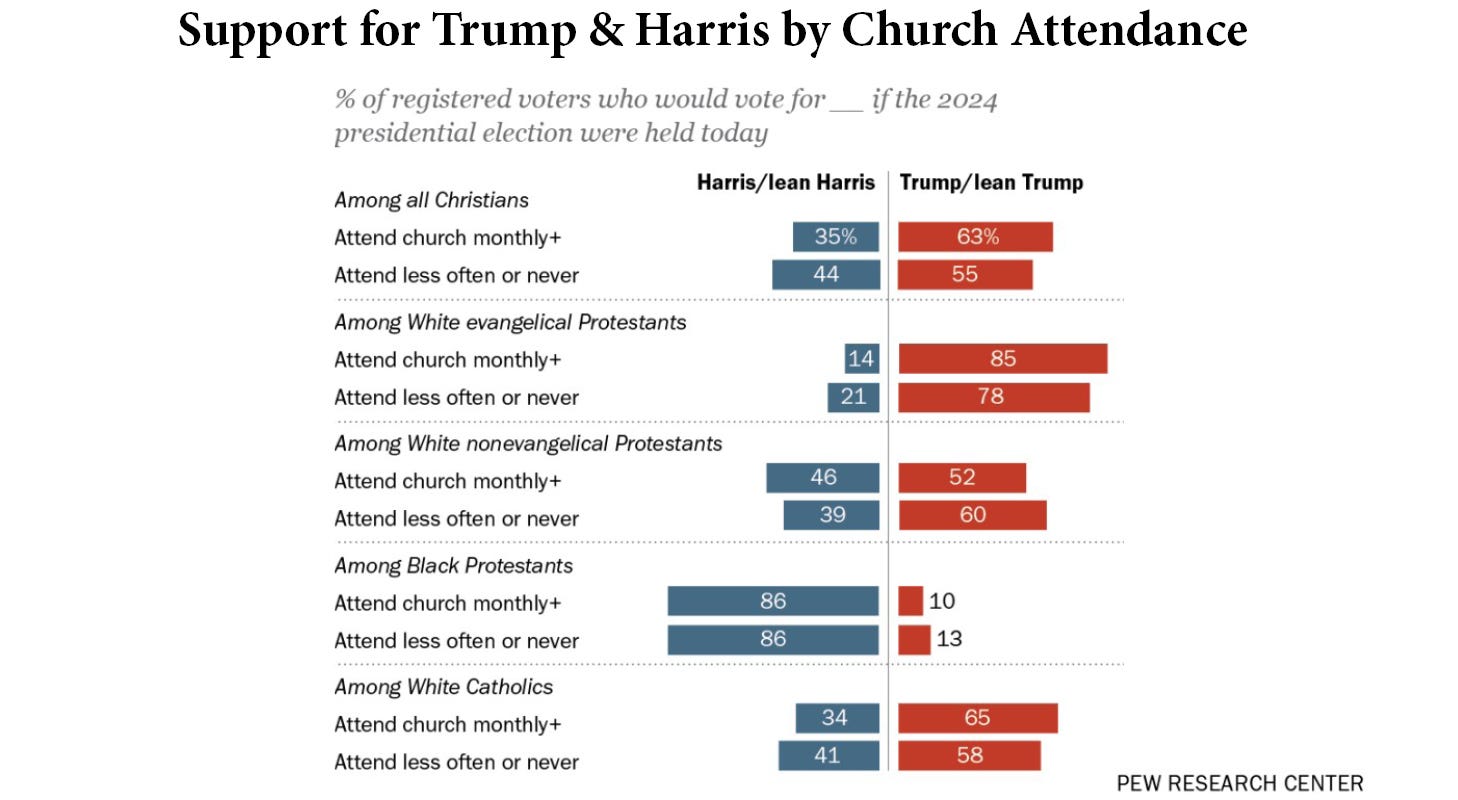

Deeper in the Pew data, there’s another finding worth highlighting: the “God gap.” One way this partisan voting difference among Christians is often analyzed is to consider the voting preferences of those who attend church more frequently versus those who rarely attend. Since the 1990s, this “God gap” has shown Republicans gaining even more support from those who attend worship more frequently. For instance, while Trump led in 2020 among those who attended services monthly or more often (59%-40%), Biden won among those who attended less often or never (58%-40%). Similar numbers occurred in 2016 as Trump led among frequent worship attenders 58%-37% while Clinton led rare or never attenders 54%-38%.

Pew’s new survey shows such a “God gap” among White evangelicals and White Catholics. While Trump leads among White evangelicals who attend monthly or more by a whopping 71 percentage points, his lead shrinks to 57 points among those who attend less frequently. Similarly, among White Catholics Trump leads among those who attend at least monthly by 31 percentage points, but he only leads among less frequent attenders by 17 points. Among Black Protestants, Pew didn’t find a significant difference. But with mainline Protestants, more regular church attendance changes the direction of support. Trump leads among those who rarely or never attend by 21 percentage points, but among those who attend monthly or more his lead cuts to just 6 points!

So while more regular church attendance correlates with a 14-point jump for Trump among White Catholics and White evangelicals, it aligns with a 15-point gain for Harris among White mainliners. It’s worth noting that this also occurred in 2020. In that election, more regular church attendance brought an 8-point swing for Trump among White evangelicals, a 21-point jump for Trump among White Catholics, and a 16-point boost for Biden among White mainliners. This reversing of the “God gap” is a major difference that warrants more attention to mainline Protestants and how they think about faith and politics.

A Different Witness

To put it in obvious but important terms: mainline Protestants are not like evangelicals. That’s literally why we have these two different categories within Protestantism. The two camps disagree on major issues. We clearly see that in politics. While more than 80% of White evangelicals continue to back Trump, he’s been unable in any election to get to 60% of White mainliners. Theologically, there are also substantial differences in how to interpret the Bible (and even which translations of the Bible to read), how to practice one’s faith, and what ethical teachings to prioritize.

Consider the issue of abortion. While 73% of White evangelicals believe abortion should be illegal in all or most cases and only 25% think it should be legal in all or most cases, that makes them an outlier. The other major Christian demographics are more likely to support abortion access. Those agreeing it should be legal in all or most cases include 71% of Black Protestants, 64% of White mainline Protestants, and 59% of Catholics. Thus, Harris’s comments during the debate Tuesday won’t win over evangelicals but are likely to resonate with many mainliners and other Christians.

This can be seen in a lawsuit filed last year by 13 clergy in Missouri to challenge the state’s near-total abortion ban on church-state separation grounds (especially since the lawmakers actually referenced God in the law). The group includes four Jewish rabbis, two Unitarian Universalists, and one Black Protestant. It also includes six mainline Protestant ministers from the Episcopal Church, United Church of Christ, and United Methodist Church. There are no evangelicals in the group.

Or consider the differences in opinion over the 2020 election, which Trump continued to falsely claim during Tuesday’s debate that he won. Most White evangelicals (60%) agree with him. However, just 38% of White mainliners (and just 38% of White Catholics) think the election was stolen from Trump. Clearly, there’s a significant worldview difference. Rather than appealing to the White evangelicals who wrongly think Trump won, Harris is likely to find more fruitful ground among the other Christians who accept the reality of the 2020 election.

Differences between evangelicals and mainliners also extend to matters of biblical interpretation and how to live out the Christian faith. Mainliners are much less likely to hold a literalistic view of the Bible. They are more likely to ordain women and LGBTQ people to ministry. And they’re more likely to engage in social justice work. For instance, the national co-chairs of the Poor People’s Campaign both come from the mainline tradition: Rev. William Barber II is a Disciples of Christ minister and Rev. Liz Theoharis is a Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) minister.

Such differences mean faith outreach would look and sound differently. Thus, it matters that the Harris-Walz campaign last month hired a mainline Protestant minister to lead faith outreach efforts. Rev. Jen Butler, a PCUSA minister and social justice activist, is the first mainliner to lead the faith outreach of the Democratic ticket since 2004. In the elections since then, Democrats hired evangelical and Pentecostal activists to lead their religious campaign efforts. This is important because the person in that role will have the most success with communities where they already have connections and with whom they have an affinity. Butler’s well-connected across religious demographics, but her years in mainline life mean she especially brings relationships with those communities.

Meanwhile, Trump’s religious outreach is still led by Pentecostal minister Paula White-Cain, which is why most of those involved in leading “evangelical” events for his campaign come from Pentecostal and charismatic churches that used to be on the fringe of the evangelical world.

It remains to be seen how the religious outreach in this campaign will go in the critical last weeks, or what impact it will actually have when people show up to vote. But over the next 53 days, it would be great to see more attention to the religious voters who will actually decide the election. We need less attention to the Charlie Brown quest to kick the football this year and instead consider important issues with the unaffiliated, Catholics, and mainline Protestants. Such coverage won’t just help us better understand the election but will also highlight a different vision of what it means to be Christian. For many unaffiliated people today, politically engaged White evangelicals are the only picture of what a Christian is.

And if anyone really wants to learn more about mainliners and politics, there’s even a new book looking at how they helped create Christian Nationalism. Oh, the things we can learn when we don’t focus just on White evangelicals!

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor