The Next Southern Baptist Investigation

Bombshell.

That’s how multiple media outlets described the 395-page report released Sunday (May 22) by Guidepost Solutions after a months-long investigation into how the Southern Baptist Convention’s Executive Committee responded to clergy sexual abuse allegations over the last two decades. The Houston Chronicle, whose investigative journalism in 2019 deserves credit for helping lead to this new report, explained how Guidepost documented the systemic efforts by leaders of the nation’s largest Protestant denomination to cover up sexual abuse and misconduct.

“The investigation sheds new and unprecedented light on the backroom politicking and deceit that has stymied attempts at reforms and allowed for widespread mistreatment of child sexual abuse victims,” Chronicle reporters Robert Downen and John Tedesco wrote Sunday. “And it exhaustively corroborates what many survivors have said for decades: that Southern Baptist leaders downplayed their own abuse crisis and instead prioritized shielding the SBC — and its hundreds of millions of dollars in annual donations — from lawsuits by abuse victims.”

Among the key findings by the independent investigation was that SBC leaders misled people about abuse issues (including in official SBC news reports) and did not report abuse allegations to authorities even when abuse occurred in their own church. SBC leaders also kept a private list of abusive ministers — even while claiming they couldn’t create such a list — but then didn’t actually warn churches or authorities. Additionally, the report details a credible allegation of sexual assault by former SBC President Johnny Hunt, who quickly stepped down as a senior VP at the SBC’s North American Mission Board ahead of the report’s public release.

All of these efforts to cover up allegations came as some of the same SBC leaders worked for years to block efforts by Southern Baptists to do more to investigate and prevent clergy sexual abuse and misconduct. Messengers to last year’s SBC meeting voted to demand an investigation into the Executive Committee with a waiving of attorney-client privilege. Many members of the EC fought the effort to waive privilege in a series of meetings last fall. But the group finally agreed on a third vote in three weeks as more than a dozen members who disagreed resigned. Despite the efforts to delay or even limit the investigation, we now have the clearest evidence to date of the extent to which SBC leaders covered up — or even committed — sexual abuse.

For the investigation, Guidepost conducted 330 interviews and attempted to interview dozens more who declined. They also looked at emails, social media, and public statements from 2000 to 2021. And yet, even with all that, it was still a narrow investigation as they were only empowered to look at the Executive Committee but not other SBC institutions (like the mission boards and seminaries) or state conventions and other entities. Additionally, they faced limitations from lack of access to some records or people who refused to cooperate. Despite those restrictions, the report is damning.

The report ends with a number of recommendations for the SBC to implement, including creating an online database of abusers and an entity to respond to allegations, limiting non-disclosure agreements so they don’t prevent abuse survivors from speaking out, and providing compensation for abuse survivors. The report and its recommendations will likely spark votes at next month’s SBC annual meeting and future Executive Committee meetings. But internal reforms are not adequate enough after the substantial documentation of likely criminal behavior by SBC leaders and ministries.

So, in this issue of A Public Witness, we call on state attorneys general to open investigations into Southern Baptist entities and conventions. After reviewing reactions to the Guidepost report, we build our case by examining the precedent set with similar state investigations into the Catholic Church.

Systemic Evil

The severity of the findings and the size of the SBC means many quickly reacted to the report’s release. Russell Moore, whose departure as head of the Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission (the SBC’s voice on public policy matters) came in part due to his criticism of the denomination’s handling of sexual abuse allegations, offered a particularly strong condemnation.

“The investigation uncovers a reality far more evil and systemic than I imagined it could be,” he wrote for Christianity Today. “When I read the back-and-forth between some of these presidents, high-ranking staff, and their lawyers, I cannot help but wonder what else this can be called but a criminal conspiracy.”

Decrying the sordid saga as an “apocalypse” for the SBC, Moore described the report as detailing “deception, stonewalling, and intimidation of victims.” He concluded, “I only know firsthand the rage of one who wonders while reading what happened on the seventh floor of that Southern Baptist building, how many children were raped, how many people were assaulted, how many screams were silenced, while we boasted that no one could reach the world for Jesus like we could.”

While not being related, Beth Moore shares more in common with Russell than a last name. The Bible teacher and author also prominently exited the SBC last year in part over the sex abuse crisis and called out SBC leaders following the release of the report.

“If you can go on your merry way in your SBC organization and carry on like nothing happened and like none of this convention rot concerns you, it will not have been ‘they’ who decayed a denomination. It will have been you,” she offered Monday in a Twitter thread. “If you can dismiss or explain away this investigative report or do the bare minimum for the sake of appearances, still denying that your men’s club mentality was in any way complicit, my head covering’s off to you.”

Kristin Kobes Du Mez, a history professor at Calvin University and author of Jesus and John Wayne, similarly connected the allegations to the SBC’s patriarchal structure in her Substack newsletter on Monday: “When ‘the gospel’ gets distorted into grasping for power, when men claim for themselves absolute authority and a host of other prerogatives, when controlling and then blaming women is the default mode, this is what you end up with.”

She also expressed pessimism about the potential for change, especially from within the denominational system. After all, the most scandalous element of the report is that the SBC leaders have “known all along” about the abuse.

“If all we hear from those with power are bland expressions of ‘shock’ and grief, without publicly confessing their own complicity, their willful silence, without remorse for ignoring or slandering survivors and their allies or failing to call out friends doing so, what we’ll see is more of the same,” she wrote. “When corruption is this entrenched, institutionally, culturally, and theologically, change isn’t going to happen because of a sudden ‘awareness.’”

Precedent for Action

With so much focus on grappling with the report’s scandalous details, attention is only beginning to shift to what happens next. But many of the solutions fail to go far enough.

Al Mohler, president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, rightly named that for the SBC, this is “a moment for sackcloth and ashes. That’s where we have to start. The gospel of Christ makes clear that that’s not where the story can end, but we’re going to be wearing sackcloth for some time to come.”

But he misses the mark in maintaining “confidence based in long experience that faithful Southern Baptist lay people, pastors, and denominational leaders will do the right thing once they know what that right thing is.” But it was the failure of lay people, pastors, and especially denominational leaders to do the right thing that led to this moment.

The report calls on the SBC to “form an independent commission and later establish a permanent administrative entity to oversee comprehensive long-term reforms concerning sexual abuse and related misconduct within the SBC.” But as Mark Wingfield pointed out for Baptist News Global, such ideas and other recommendations in the report have been stymied for years by those in SBC leadership, despite demands made by sexual abuse survivors and other advocates for reform.

The unfortunate reality is that, absent an entire (and unlikely) turnover of denominational leadership, any action taken by the SBC will lack credibility. The individuals, organizations, and processes that failed to address this evil cannot be the ones entrusted with repairing the damage and preventing future harm, especially when so many questions about culpability and accountability remain unresolved.

Additionally, the behavior documented in the report aren’t just spiritual or organizational sins but at times even criminal behavior by SBC leaders. As Russell Moore noted, “criminal conspiracy” may be the most apt label to what’s documented in the report. His words raise the prospect of another avenue for finding justice: investigations by state attorneys general.

The SBC is not the first religious body to face a sex abuse crisis. Most notably, the U.S. Catholic Church has been roiled by accusations about abusive priests and efforts by officials to deny, cover up, or quietly resolve such issues. The systemic, decades-long nature of the problem led AGs in at least 22 states to look into potential crimes (you can find updates about many of those investigations from the independent Catholic Substack newsletter The Pillar).

Those efforts proved consequential. In Pennsylvania, a grand jury report illuminated the magnitude of the problem, prompted changes to the state’s child abuse statutes, and garnered a conciliatory response from Pope Francis. In Massachusetts, a jury convicted a senior prelate for child endangerment because of his role covering up abuse by priests. In Missouri, AG Eric Schmitt referred a dozen cases of potential clergy abuse to local prosecutors (to conclude an investigation first launched by then-AG Josh Hawley, whose approach to the matter received criticism).

Many are noting similarities between the Catholic scandals that led to those investigations and the revelations about the SBC. As Marci Hamilton, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania and CEO of CHILD USA, a nonprofit think tank working to end child abuse and neglect, told us, “The SBC coverup of sex abuse and assault fits the paradigm we first saw in the Catholic Church in 2002. The needs of the victims were secondary to concerns about dollars and image. Similarly, victims were religiously intimidated from seeking justice.”

With a new report now documenting how SBC leaders, like Catholic ones, engaged in extensive efforts to cover up abuse and protect the accused, similar state AG investigations are warranted. And calling for such action by state AGs is not without precedent.

Time for AGs to Act

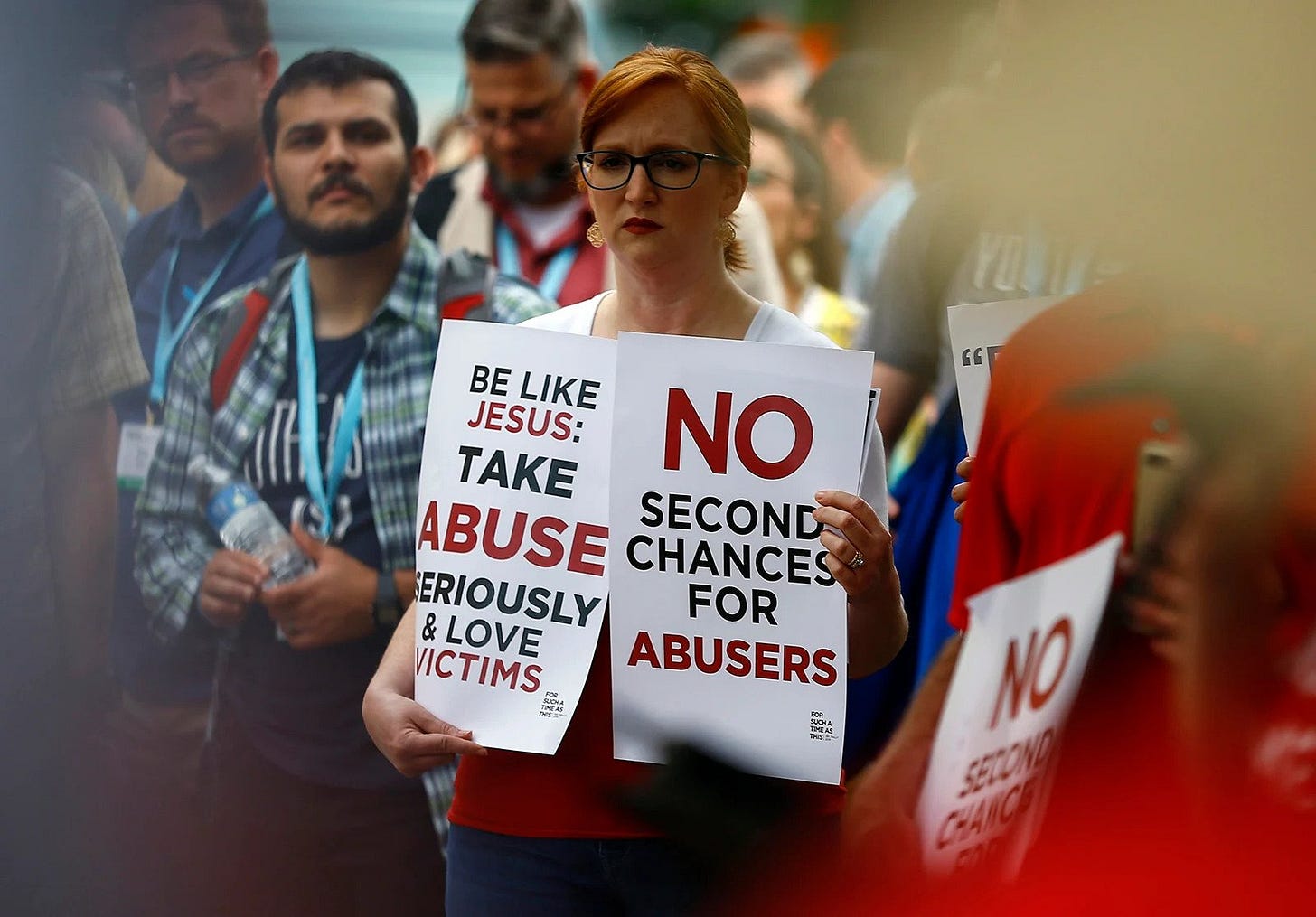

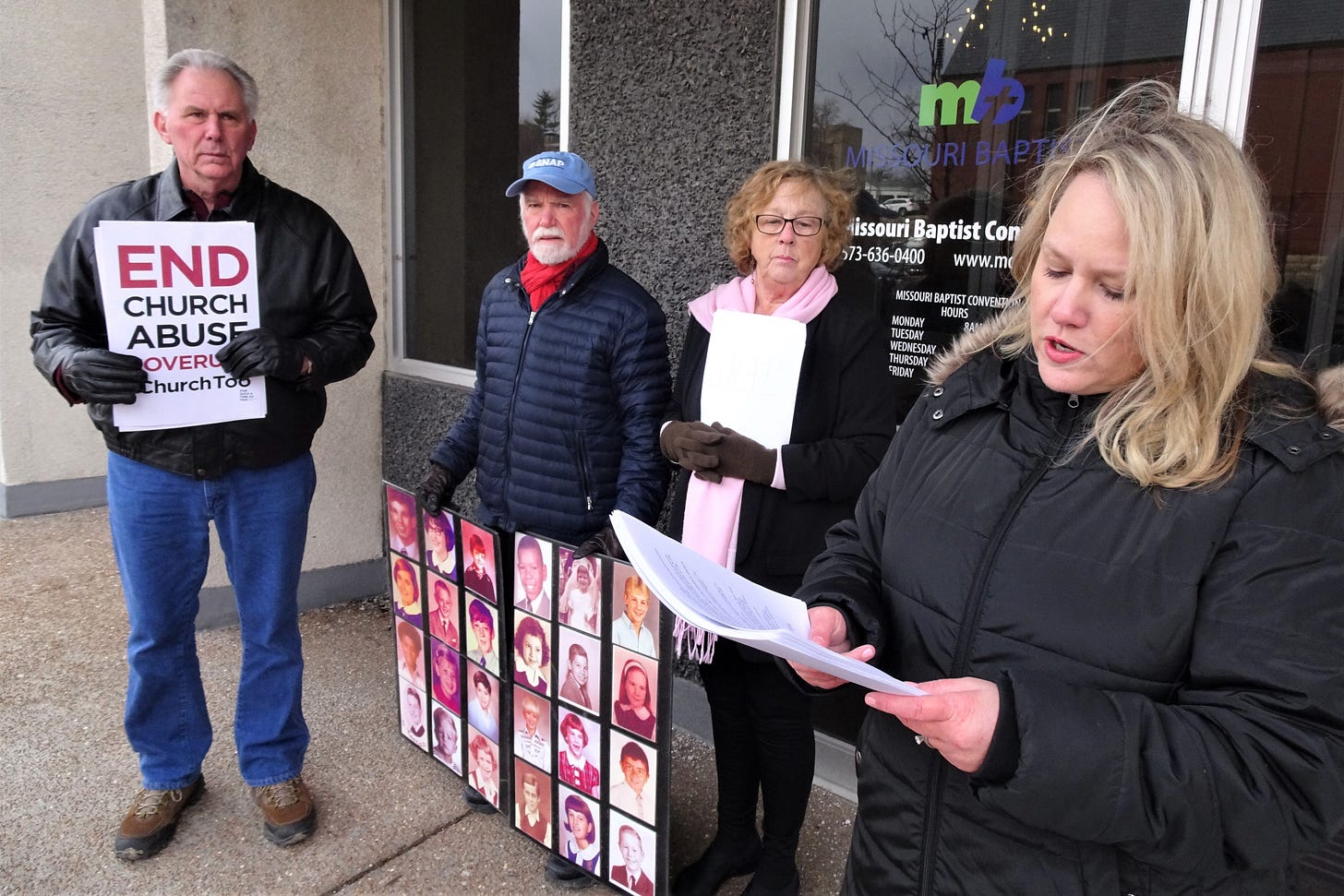

On Feb. 26, 2020, advocates for survivors of clergy sexual abuse stood outside the headquarters of the Missouri Baptist Convention to request that Missouri AG Eric Schmitt formally investigate Missouri Baptist clergy like he had done with Catholic priests. The two groups calling on Schmitt to act were For Such a Time as This Rally that advocates for abuse victims within the SBC and the Survivors Network for those Abused by Priests, a group formed in 1989 to draw attention to clergy misconduct within the Catholic Church. (Today, SNAP has 12,000 members in more than 50 nations, and it also advocates for victims in other religious traditions.)

The impetus for the call was the controversy that erupted after MBC leaders defended a pastor, Mike Roy, accused by police of not properly handling a case of a staff member sexually abusing boys. After learning of the allegations against Roy, Southwest Baptist University in Bolivar, Missouri, announced a few days before the protest that it would investigate the claims since Roy had recently joined the school’s board of trustees. Roy was among the trustees chosen by the MBC’s Nominating Committee after that committee rejected nominees by SBU and misled MBC messengers about the nomination process amid the three-year conflict over power and theology at the school. MBC leaders then attacked SBU for investigating the claims, which sparked the event calling on Schmitt to investigate.

Schmitt, who is Catholic, did not open an investigation into Southern Baptist clergy abuse. And the MBC increased its control over SBU, leading to the resignation of the president who criticized Roy’s presence on the board. Roy not only remained on the board but was also put on the presidential search committee — a move that garnered criticism from SNAP.

The new report on SBC clergy sexual abuse shows the systemic nature of such behavior in Southern Baptist life. That’s why state AGs across the country should act. SNAP Executive Director Zach Hiner sees the need for such investigations after “this bombshell report into abuse and cover-up” in SBC life. He praised “survivors like Christa Brown” for helping bring this to light but also called for more investigations.

“Just like with the Catholic Church, we have a clear example of rot at the top and we know that when leadership is actively looking the other way, no ‘internal investigation’ can have any real merit,” Hiner told us. “Given that the SBC appears to have followed the Catholic Church’s playbook when it comes to enabling and covering up the abuse of children and adults, so too should the SBC face the same kind of external scrutiny. We firmly believe that no institution is capable of policing itself and we believe that it is incumbent on the attorney general in all 50 states to look closely into how SBC churches have operated within their states and whether there are crimes that can be prosecuted. Now that the attention is squarely on the SBC and their decades-long mishandling of sexual abuse cases, we are confident that survivors who have been shamed and scared into silence will feel a renewed call to come forward, and we believe that it is attorneys general to whom reports should be made.”

Similarly, Albert Scherr, a professor at the University of New Hampshire School of Law, told us “there’s really two types of legal actions you may see” in light of the new report.

“You may see more individual actions by prosecutors against individual ministers or authorities within the Convention just for engaging in the abuse themselves. Those could be civil lawsuits, individual civil lawsuits for damages, or they could be criminal actions,” Scheer explained. “The second type of action is the basically conspiracy of silence type of action. That’s certainly happened. The attorney general’s office in New Hampshire brought that kind of action against the Catholic diocese here.”

He noted the “caveat,” however, that the possibility of AG actions would “depend on the state” because of the “mix of religion and politics and money.”

We contacted multiple state attorneys general, including Tennessee’s AG where the SBC is headquartered, to inquire about their awareness of the report and any plans to investigate based on its findings. Some didn’t respond, like Schmitt in Missouri. Maryland’s AG office responded that it “does not confirm or deny the existence of investigations.” Tennessee’s AG office, which did not launch an investigation into Catholic clergy, explained that their office, “unlike other states, does not have original criminal jurisdiction. An investigation and potential charges would start with local district attorneys.”

But Wisconsin’s AG office suggested such an investigation could come: “Although the Wisconsin Department of Justice started with the Catholic Church in this initiative, victims are encouraged to report sexual abuse committed in any religious organization. As with any report of abuse received, DOJ will endeavor to connect the victim with appropriate support services. DOJ also will encourage victims to report abuse to local law enforcement or will do likewise with permission from the victim.”

We suspect it’s only a matter of time before a state AG launches an investigation into Southern Baptist clergy in their state like we’ve seen with Catholic clergy. And as occurred with Catholics after Pennsylvania started the trend, other states will likely follow suit. We hope such investigations start sooner than later. Too much time has already passed with too many victims left ignored by a bureaucracy that cared more about avoiding lawsuits, protecting abusers’ reputations, and preserving personal and denominational power.

Sackcloth and ashes aren’t enough. Some may also need jumpsuits and handcuffs.

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor & Beau Underwood

When the "Bombshell" exploded I was sure B & B would be on top of the story. So much appreciate your perspective. It will be interesting to see what comes out of the SBC Annual Meeting on this matter. In my skeptical mind, I had little confidence in what would be forthcoming in the Report. I do plan on putting aside the time to read it for myself. It was so far worse than I had imagined. The use of the phrase "Criminal Conspiracy" does not appear to be out of line at all from my perspective. We will simply have to wait and see what happens. As an outsider looking in, I have my doubts as to what extent real repentance will take place, but I may be surprised. I know B & B will keep providing a faithful and free witness on this important situation in Baptist life.

I hope that appropriate actions will lead to not only catching perpetrators quickly, but preventing some potential perpetrators from acting on their impulses. I attend a church which requires both preventive measures like having two adults present for youth activities and training for both volunteers and staff in recognizing signs of incipient abuse. I also worked for a decade in a clinic which treated both offenders and victims. Then a family member was caught. It is possible that if this man, or others, had been required to undergo the training which I had before I could teach a Sunday School class, he might have seen himself in that training and either decided to not work with children, or to face his own problems first. If the training and associated introspection keeps even a few persons from committing crimes, that's even better than catching perpetrators quickly. It's still true that it's those who have not been caught who are the greatest danger to both children and vulnerable adults. I should add that one who has been caught, if he/she has responded to effective treatment, will, for the rest of his/her life, be responsible for avoiding any future temptation. My relative, who lived long enough that few people knew what he had done, ever after avoided any work or occasion where he could be either tempted or accused. The reason for background checks is that those who don't monitor themselves are the ones most in need of it.