The Trump Administration’s Favorite Fake Prayer Story

In September, the White House launched a new “America Prays” initiative to encourage Americans to gather together “with at least 10 people” and devote “one hour per week to praying for our country and our people.” They inaccurately claimed the Southern Baptist Convention endorsed the effort and haven’t really made any edits to the site since President Donald Trump announced it during a meeting of his “Religious Liberty Commission” at the Museum of the Bible. Except to change the main picture for the initiative.

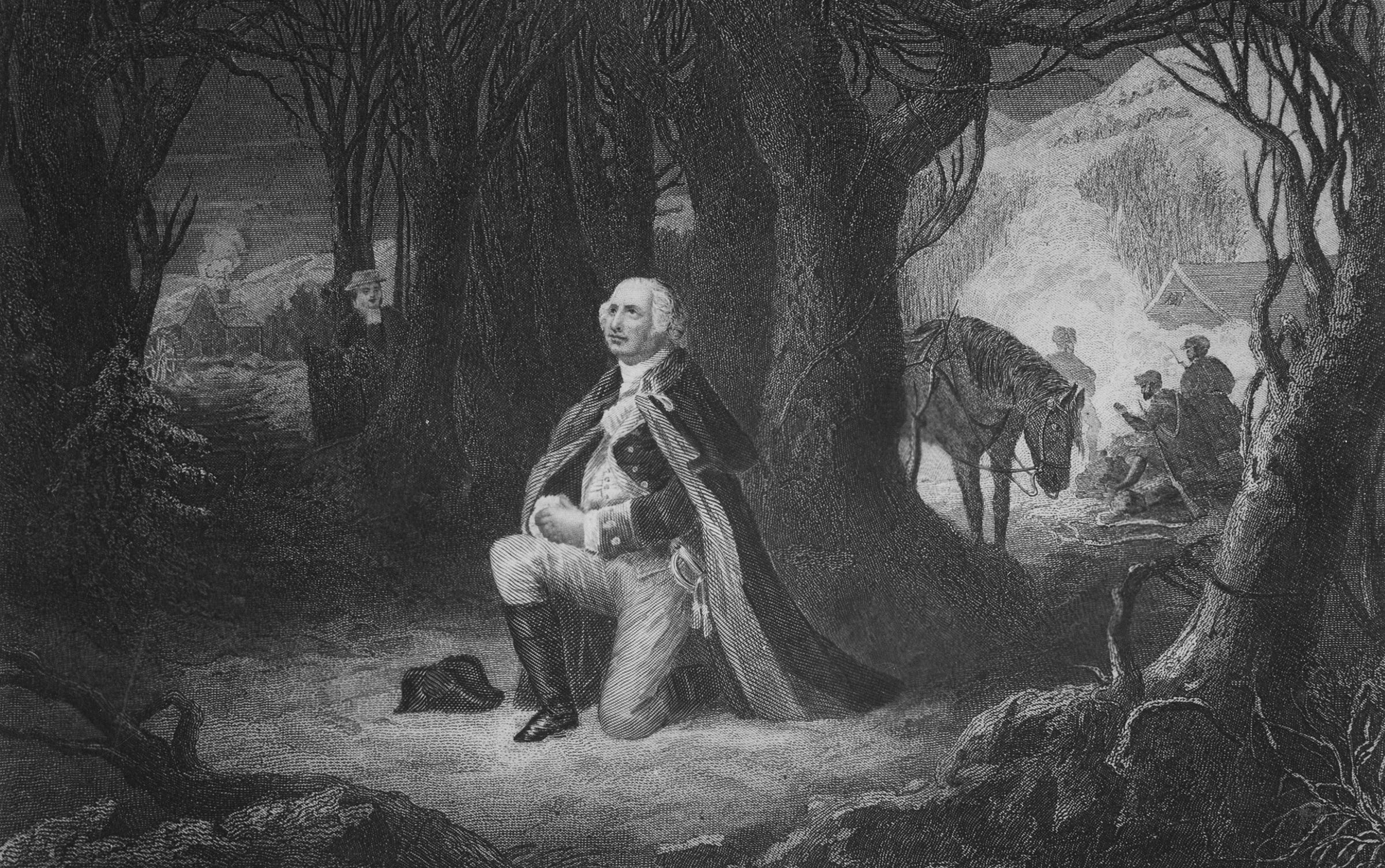

At the top of the White House site, it says the effort is to rededicate “the United States as one nation under God.” And then they posted an image of George Washington praying on bended knee in the snow next to a horse while in Valley Forge during the Revolutionary War. At first, they posted an ugly, apparently AI-generated version. By the day after Trump’s announcement, the site had been updated to feature the same scene but a more famous version by artist Arnold Friberg. He painted “The Prayer at Valley Forge” 50 years ago for the U.S. Bicentennial celebration.

The Trump administration likes Friberg’s image as they push Christianity as part of the celebrations of the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence next July. The Department of War posted the painting on social media on Nov. 16 along with the caption, “For 250 years, America’s military has appealed to Heaven.” The Department of Labor shared it on social media on Sunday morning, adding, “May God bless our nation and her people.” And Secretary of War Pete Hegseth referred to the story of Washington praying during his remarks at a Christmas tree lighting at the Pentagon yesterday (echoing similar remarks about Washington praying that he made during first of the monthly prayer services he’s been leading at the Pentagon).

There’s a bit of a problem with all of the uses of Friberg’s painting or other renditions of Washington praying at Valley Forge (whether created by AI or not): It’s based on a myth.

There’s no evidence the moment ever happened, and the original story included inaccurate details from someone known to have made up stories about Washington. Yet, this false story is held up now as “evidence” that America was built on prayer and is “one nation under God” (even though God wasn’t actually added to the Pledge until 1954, which is long after Washington was at Valley Forge).

Despite that, as these few recent moments show, we’re likely to see the painting and hear the story a lot in the coming months as we near the Semiquincentennial on the Fourth of July. It’ll be repeatedly used as “proof” the U.S. should be a “Christian nation.” So this issue of A Public Witness looks at the truth behind this Christian Nationalist fable.

Unreliable Narrator

Episcopal minister Mason Weems preached some at the church where George Washington attended prior to the Revolutionary War. But in his later retellings, Weems gave himself a stronger Washington tie, calling himself the “rector of Mount-Vernon parish.” He used that exaggerated connection to promote his book, A History of the Life and Death, Virtues and Exploits of General George Washington. First published in 1800 — the year after Washington’s death — it was a popular book that he repeatedly expanded with many editions as he added new stories.

The problem is the book is often more hagiography than biography. And Weems was less concerned with getting things accurate than advancing moral lessons with his stories. As historian François Furstenberg explained in his book, In the Name of the Father: Washington’s Legacy, Slavery, and the Making of a Nation, “Weems would use Washington to teach virtue to America’s youth.” So some of the stories in the book are believed by historians to be made up.

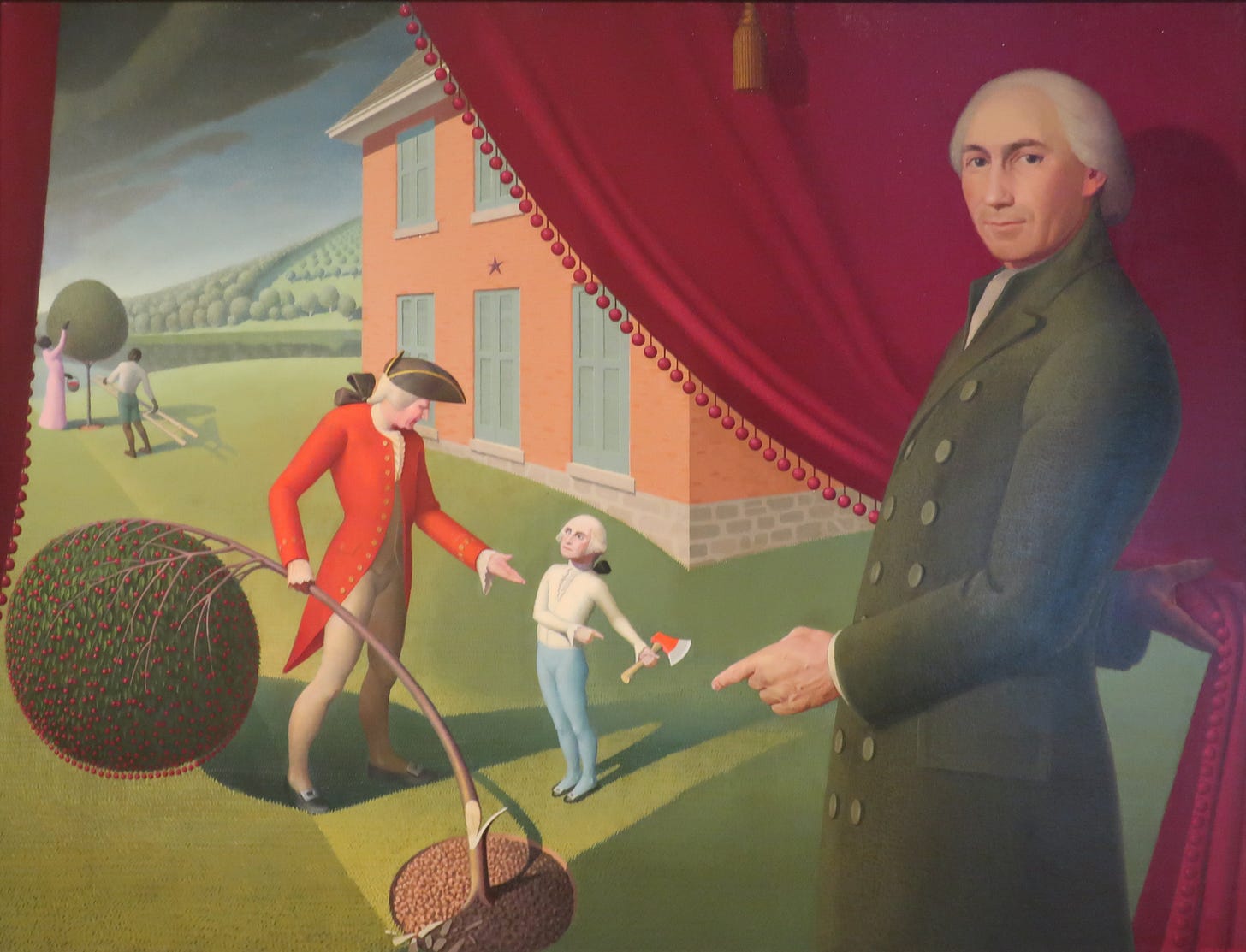

Like the one about little George chopping down the cherry tree.

Yes, that’s right, a story we teach to children to highlight the importance of telling the truth is itself a lie. Perhaps that’s why it wasn’t even originally in the book.

As Weems’s stories were popular and he kept printing new versions, he added the cherry tree story to a new edition a few years later. He also added a story about Washington’s praying at Valley Forge during the Revolutionary War. And it too is a myth.

“Almost certainly sprung from Weems’s imagination, this portrayal of Washington’s religiosity would be disseminated not only textually but also pictorially, teaching children of Washington’s supposedly overt piety, and urging them to emulate his example,” Furstenberg explained. “The image of Washington as a not-so-closet evangelical continues to resonate in debates today about the religious leanings of the Founding Fathers, a subject on which Weems was something of a pioneer. “

Weems claimed to know about Washington’s private moment of prayer because it was secretly viewed by Isaac Potts, a Quaker. But Potts was actually living elsewhere during that time, so it’s highly unlikely he would’ve been around to witness it. By the time Weems wrote the story, Potts — like Washington — had died, and thus could not dispute the claim.

Early artwork depicting the story often included Potts peeking out behind a tree. He’s since been largely erased from the renditions, including the famous painting by Friberg. Apparently, the legend’s so accepted now we no longer need to include the alleged eyewitness. Or perhaps we are now made the witnesses, as if we are Potts. But if we remember the real Potts, we see a problem with Weems’s story that goes beyond geography. This isn’t just a work of fiction; it’s also a defamatory attack on someone’s religious beliefs.

A Different Faith

Weems went into his Washington project with an ideological agenda (in addition to a capitalistic one). As Furstenberg noted, “Weems merged Christian benevolence and republican antipartisanship into a nationalist rhetoric of ‘love’ — love among siblings of a common father — in order to unite Americans.” He wanted to teach virtue and push a vision of a Christian nation. But not all Christians fit with his nationalistic theology. Like Quakers.

Weems could’ve chosen any (dead) person as the alleged witness and thus source of Washington praying at Valley Forge. But he chose a Quaker. Why? Because the story doesn’t end with Washington’s prayer. Weems’s tall tale also includes the supposed impact of the moment on Potts. Weems has Potts head home to his wife (but got her name wrong) to announce he was giving up the pacifism of his Quaker faith.

“I always thought that the sword and the gospel were utterly inconsistent. But George Washington has this day convinced me of my mistake,” Weems’s Potts declared, adding he now believed “Washington will yet prevail” and “work out a great salvation for America.”

This is another reason people have questioned the story for nearly two centuries. There’s no evidence Potts ever abandoned his Quaker faith, and he’s buried in a Quaker cemetery.

This is more insidious than just making something up. Weems used his story to suggest that Christians who didn’t support nationalistic war were politically and religiously wrong. If only they would understand true piety and religiosity, they too could be converted like Potts to a more enlightened version of Christianity. Because of their pacifism and often their neutrality (if not opposition) during the Revolutionary War, Quakers faced some persecution. On the first anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, some patriots broke the windows of Quakers in Philadelphia. Others were forced at gunpoint to help the war effort. And Washington even ordered Quakers to be intercepted as they traveled through the area.

Weems played on that distrust of Quakers to create a dramatic conversion akin to Moses at the burning bush or Saul/Paul on the road to Damascus. But in doing so, he also argued Quakers were inherently un-American and religiously deviant. They needed to convert. And the savior who would set them straight was a politician. By becoming good Americans, they could become good Christians.

And that’s what Christian Nationalists do today with the fable. They suggest that those who don’t accept their faith aren’t real Americans and aren’t real Christians. But I cannot tell a lie: Christian Nationalism is based on fake history and bad theology.

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor

In place of Washington's fabricated picture of prayer, we need to revisit Luke 18's picture of the persistent praying widow...

. 7 And will not God bring about justice for his chosen ones, who cry out to him day and night? Will he keep putting them off? 8 I tell you, he will see that they get justice, and quickly. However, when the Son of Man comes, will he find faith on the earth?”

We must be persistent in our prayers for justice AND in our resistance to Christian Nationalism.

Friend Brian, once again you have done a great service to history and to truth!! While I was aware of some of the falsehoods, myths, legends, and general misinformation of the Washington praying in the snow at Valley Forge, you expanded my knowledge. It may be that the Trump-Hegseth coalition so loves this "story" because it is steeped in falsehood, myth, legend and misinformation, the stock in trade for both of these men. One of the things that has always struck me about the Valley Forge prayer story is that Washington is generally considered a diest in his theology, as my research has revealed. That is not to say he may not have prayed for the intervention of "Providence," however, to present him as something akin to an evangelical Christian is to misrepresent his personal faith. The alleged Valley Forge prayer is an extremely weak foundation for building a government sponsored and endorsed program of prayer. Can not people of every thrological stripe and bent engage in our prayers in whatever fashion and manner we are led without the imprimator of the government? Of course, we can, we should and we must!! Our exercise of faith should never be tired to any government advocated, and directed political-religious endeavor.