The War on CRT

Note: If this is your first issue of A Public Witness in a few weeks, then you likely are signed up for just a free subscription. Upgrade to a paid subscription to read the archives of what you missed and to receive every future issue, including the one we’ll be sending out next week only to paid subscribers.

The date was May 19, 1992.

Vice President Dan Quayle traveled to California just a couple weeks after riots in Los Angeles following the acquittal of police officers charged with beating Rodney King. After condemning the riots, Quayle said, “We do need to try to understand the underlying situation.” He then used the bulk of his speech to reframe the situation in terms of family breakdown, famously referencing a TV sitcom.

“Marriage is a moral issue that requires cultural consensus and the use of social sanctions,” he said. “It doesn’t help matters when primetime TV has Murphy Brown, a character who supposedly epitomizes today’s intelligent, highly-paid professional woman, mocking the importance of fathers by bearing a child alone and calling it just another lifestyle.”

Rather than address critical issues of racism, policing, or even violence, Quayle used the riots that left 63 people dead and thousands injured as a chance for firing shots in a culture war during his reelection campaign. Other Republicans, including President George H.W. Bush joined the fight against Murphy Brown. And even then this rhetoric seemed odd. What choice would Quayle have wanted a real-life person in Brown’s situation to make once she found herself pregnant? Abortion? But in a culture war, there’s no room for such nuance. Who “we” are is under threat, and “they” must be defeated.

The terminology of “culture war” was first coined by sociologist James Davison Hunter in his 1991 book, Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America. As he explained during the 1992 campaign, even when these flashpoints seem silly or misrepresented, they point to something large since “the culture war is about who we are as a nation and who we will choose to become.”

“The tiff over Murphy Brown is just an artifact of a deeper dispute over the nature and structure of the American family,” Hunter wrote in 1992. “The culture war, then, will be with us for many years to come. Count on it.”

And he was right. But as we watch another round of culture war political rhetoric that often seems as outlandish as a vice president attacking a TV character, we think Hunter was right about something else in 1992.

“It is,” he wrote, “time to stop the drum-beating. What we require is serious and substantive argument inspired by a leadership that is both bold and rhetorically circumspect. For in a democracy, how we contend in public life is as important as what we contend for.”

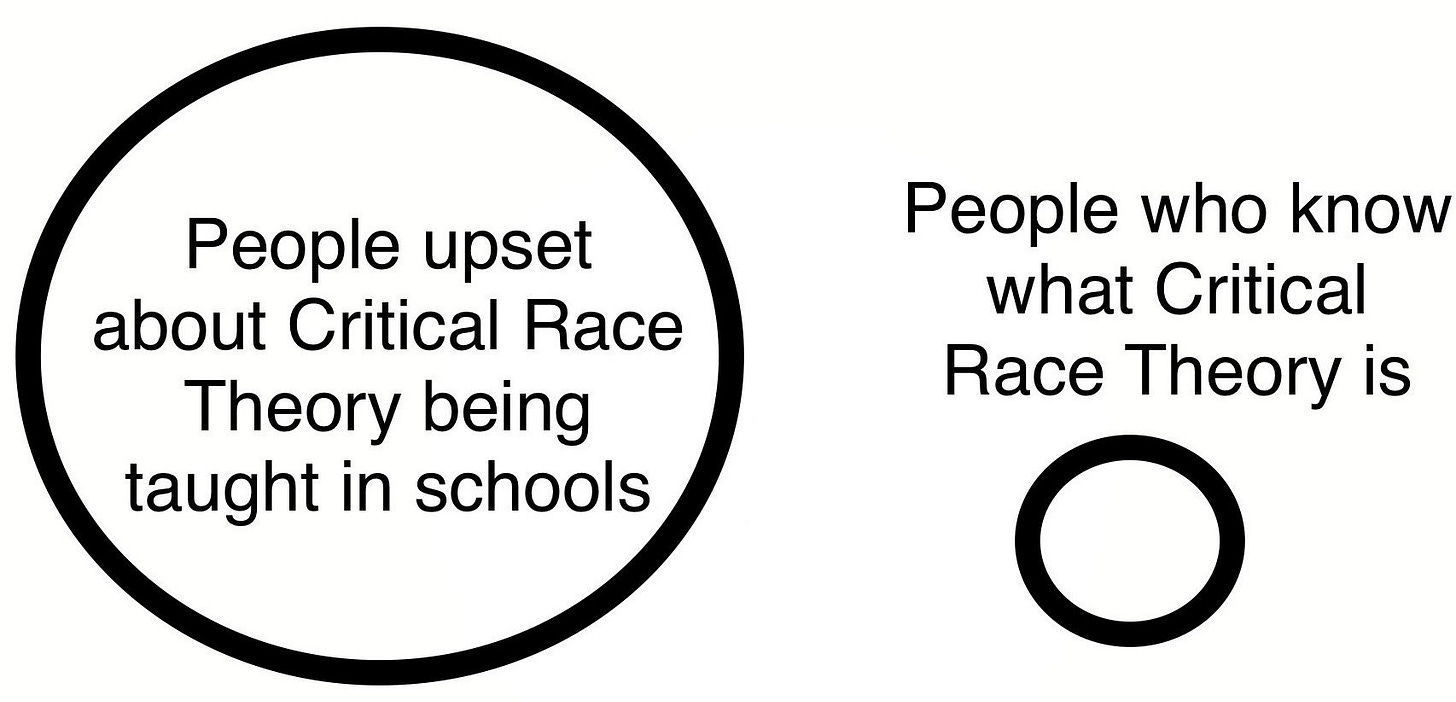

In this edition of A Public Witness, we explore the newest culture war that is unfolding around Critical Race Theory. We question the motives of those who started the fight, the degree that those who picked up arms actually understand what CRT is all about, and a key Christian doctrine we risk abandoning by joining the new culture war of “us” versus “them.”

What is Critical Race Theory Anyways?

Until recently, almost no one outside of universities had heard of CRT. That’s not surprising because CRT is a complex body of academic literature — and probably should more accurately be known as critical race theories — that few non-scholars have actually read. In fact, neither of us encountered these ideas — or critical theories more broadly — until our own graduate studies. So, here’s a brief explanation to ensure we’re all talking about the same thing.

Beginning in the late 1970s, legal scholars like Derrick Bell, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Richard Delgado, and Mari Matsuda began exploring how laws created and extended racism. By considering racial inequities baked into the system, they helped illuminate past injustices with lingering consequences today. Consider:

In the 1930s, government officials marked neighborhoods on maps considered financially risky — merely because of the racial makeup of the residents — and that meant many banks refused to lend for houses in those areas. This redlining cut off non-Whites from home loans that helped build the White middle class in the mid-20th century. And it meant Black residents in these areas had little equity to pass on to the next generation, creating a multi-generational cycle of racial economic inequality. CRT scholarship reminds us to identify the negative, long-term effects of policies deliberately targeting minorities.

After World War II, many veterans received a college education through the G.I. Bill. This created opportunities for climbing up the economic ladder but only if the veteran was White. Others found themselves left out of the program and falling behind those they had fought next to in the war. Since parental education is correlated with college attendance, another cycle of inequality was born. CRT scholarship tells us why a “colorblind” look at the past doesn’t work because it ignores why some veterans received benefits over others.

These two examples prove the larger point: racism is not a mere aberration in U.S. society. It is often in the design, sometimes literally. The Constitution counted Blacks as three-fifths of a person to increase the voting power of wealthy White enslavers. Ending slavery led to new laws and systems codifying and enforcing segregation that preserved White political influence. An honest retelling of history forces us to face these uncomfortable facts. As CRT scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, executive director of the African American Policy Forum, explained, this work is “simply about telling a more complete story of who we are.”

CRT emerged a decade after the death of Martin Luther King, Jr. and roughly 15 years after major civil rights movement victories like the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act. While those successes were important, the racial wealth gap and de facto segregation lingered. CRT scholars argued a wider lens was necessary for understanding why.

“Critical race theory is an effort really to move beyond the focus on finding fault by impugning racist motives, racist bias, racist prejudice, racist animus, and hatred to individuals, and looking at the ways in which racial inequality is embedded in structures in ways of which we are very often unaware,” explained Kendall Thomas, co-editor of Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings That Formed the Movement.

CRT therefore is focused on systemic impacts, not personal racism. Chief Justice John Roberts famously declared in a ruling, “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” But for CRT scholars that leaves too much unacknowledged and unaddressed. They are less concerned with trying to imagine the inner feelings of individuals than exploring the quantifiable real-world impacts of laws and policies. Racism doesn’t just happen. Like race itself, racism is socially constructed and created through legal systems. So, CRT scholars look at the racial effects — even unintended ones — of various policies.

Such scholarship is understandably activist in nature. To expose a law creating racial inequity is to challenge the continued enforcement of it. As David Miguel Gray, a philosophy professor at the University of Memphis, explained, “Critical race theory provides techniques to analyze U.S. history and legal institutions by acknowledging that racial problems do not go away when we leave them unaddressed.”

Why Talk About It Now?

The current debates over CRT seem far afield from these historical and scholarly accounts. That is intentional. Identifying who fired the first shot in this cultural war is almost impossible, but one of the main antagonists is Christopher Rufo, who is affiliated with a think tank called the Manhattan Institute. On Twitter, he said “the quiet part loud.”

“We have successfully frozen their brand — ‘critical race theory’ — into the public conversation and are steadily driving up negative perceptions. We will eventually turn it toxic, as we put all of the various cultural insanities under that brand category,” he declared. “The goal is to have the public read something crazy in the newspaper and immediately think ‘critical race theory.’ We have decodified the term and will recodify it to annex the entire range of cultural constructions that are unpopular with Americans.”

His logic has a certain nihilistic flavor: the goal is to make CRT meaningless (decodify) so that it can be reconstructed (recodified) to represent anything Americans detest. Even for a soldier in the cultural war, this is stunningly brazen. “Truth” is defined by elites for their own political purposes.

Rufo has found a willing accomplice in Fox News. Hosts and guests on the cable channel have mentioned CRT thousands of times in 2021 already, a tenfold increase from all of 2020. The coverage has been far from “fair and balanced.” Tucker Carlson, who has a history of airing racially problematic segments, is a particularly vocal critic in equating CRT to “White genocide.”

The conservative commentator Charlie Sykes refers to this as “a shark attack party,” using the analogy of the media sensationalizing rare reports of sharks coming after humans. He explained that “even the rarest occurrence can seem like a crisis if it is amplified and dramatized by media coverage.” With regards to the current controversies over CRT, he added, “It’s almost as if someone decided that this was going to be a thing … and lo and behold … it became one.”

All these efforts convinced at least one person.

The Washington Post reported how then-President Donald Trump was watching Fox News last summer when a segment about CRT came on featuring none other than … Christopher Rufo. During the appearance, Rufo claimed that “Critical Race Theory has become, in essence, the default ideology of the federal bureaucracy and is now being weaponized against the American people.”

According to the story: “The reaction to Rufo’s appearance that evening on Fox News was swift. The next day, Trump demanded action. Two days later his budget chief issues a memo laying the groundwork for the federal government to cancel all diversity trainings. An executive order followed, and Rufo was invited to the White House a few months later for a meeting.”

Gasoline was poured on the fire of this emerging culture war.

Now, the former president’s political advisors and allies are doing everything they can to stoke the flames because of the political potential they see in creating a controversy over CRT.

“This is the Tea Party to the 10th power,” Trump campaign manager and White House strategist Steve Bannon told Politico. “This isn’t [the QAnon conspiracy theory], this is mainstream suburban moms — and a lot of these people aren’t Trump voters.”

Now Republican officials are seeking to ban the teaching of CRT in public schools and state universities. Organizations are monitoring local school districts and ginning controversies with the effect that, “school boards are now facing an influx of lawsuits and records requests that can cost money and time that are in short supply, as well as public meetings that have become a sounding board for a variety of far-right causes.” And, of course, they’re fundraising off the pandemonium.

You can interpret these events as a cynical push to raise money and rally voters. Or a desperate attempt to drive up sagging cable news ratings. You could note the hypocrisy over opposing the teaching of Critical Race theory while defending Confederate monuments as important historical reminders. You could question whether all these efforts amount to “cancel culture” or even infringements on the constitutional right to free speech.

Those are discussions to be held by different people in other places. We want to ask what stance Christians should take towards Critical Race Theory. What does the witness of the Bible have to say in response to all this manufactured controversy?

CRT & Original Sin

As noted above, Critical Race Theory is a diverse and nuanced academic literature. It is a broad set of ideas that legal and other scholars use to analyze and understand history. While neither of us are experts in the field, we accept the basic idea that racism has been embedded within the structures of the United States in ways that continue to negatively influence society today. So, in essence, CRT claims that a profound initial mistake (racial oppression/slavery) distorts the unfolding history of the country.

That sounds an awful lot like the Christian doctrine of original sin.

Many Christians affirm the idea that from the beginning of time — from the very first humans onward — the reality of sin is inescapable. As the Apostle Paul writes in Romans 5:12, “just as sin entered the world through [Adam], and death through sin, and in this way death came to all people, because all sinned.”

Our inability to avoid sin has profound implications. Not only does it separate us from God in a way that requires Christ’s intervention (Romans 5:8), but it also prevents us from clearly seeing what God is doing. Sin warps our perception of the world until God puts everything right. Here, again, Paul eloquently states, “For now we see only a reflection as in a mirror; then we shall see face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully” (1 Corinthians 13:12).

It is hard to see much difference between this basic Christian doctrine and the claims of CRT. Human sin, of which racism is certainly one, has lasting effects on humans that deform our lives absent the redeeming activity of God. There is no individual life or human-created structure exempt from this theological truth. Nor is there any human effort capable of correcting it. A grace from beyond ourselves is the only healing balm.

Jim Wallis, the evangelical writer and activist, noted the history America must face: “Ironically and tragically, American diversity began with acts of violent racial oppression that I am calling ‘America’s original sin’ — the theft of land from Indigenous people who were either killed or removed and the enslavement of millions of Africans who became America’s greatest economic resource — in building a new nation. The theft of land and the violent exploitation of labor were embedded in America’s origins.”

The scandal here is not in what CRT teaches but in the depth of human sin to which it points. Christian theology has long told a story about God, human nature, and the presence of sin. Followers of Jesus Christ who vigorously oppose the claims of CRT have suddenly forgotten this fundamental claim of the faith they profess.

Perhaps that is because their love of country causes them to struggle with the difficult facts of American history. Or maybe partisan tribalism overwhelms one’s ability to analyze this debate through a Christian lens. Whatever the cause, the inability to see and name sin is just more evidence of Paul’s judgment about our clouded vision.

The Truth Will Set Us Free

Dealing with such heavy issues is challenging work. There is the pain of confession and the formidable effort of repairing the damage and tending to societal scars. Rather than squarely facing reality, this cultural war over CRT distracts us from talking about what really matters. As CRT scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw explained, “You can’t fix a problem that you can’t name.”

Whether it’s attacking a fictional TV character in 1992 or creating a TV caricature of CRT in 2021, such rhetoric keeps us from focusing on what really matters. And that’s the point. As ethicist David Gushee wrote, we see this backlash to ideas like CRT “when people who have been lying to themselves for hundreds of years are challenged. We wish to retain not just our supremacy but our innocence. It is the challenging of our innocence that so outrages us.” But as Christians we must tell the truth, including the truth about our original sins.

Refusing to talk about the whole story of our past prevents Christians from honestly talking about the pervasiveness of sin and how human beings created in the Image of God have been (and are) intentionally prevented from flourishing as our Creator intends. And we won’t solve these societal problems without Christians having these honest conversations. Indeed, Andre E. Johnson, a communication scholar and pastor, noted that “while more people are hearing more — and hopefully learning more — about CRT, more are also opposing it because they believe their faith teaches them to do so.”

If we close our eyes to reality, we risk missing out on God’s redeeming work in the world. Rather than learning from the transgressions of our past and their impact on the present, we will repeat the political and religious errors that led Christians to justifying slavery, promoting lynchings, enforcing Jim Crow segregation, and opposing Black Christians who marched for freedom. If we allow cable news talking heads to distract us with their distorted version of what CRT means, it could even keep us from reading in the Bible the very path toward redemption that we desperately need.

“Scripture was actually written in the context of oppression,” author and activist Lisa Sharon Harper says in an upcoming episode of the Dangerous Dogma podcast. “So, the question of power, the question of racialization, it is actually all over the Gospels. If you have eyes to see it, it’s right there in front of your face. But if you are looking at the Scripture from the social location of Empire, from the social location of the halls of European academia, you’re going to miss it, you’re going to read the Scripture as if it was written at Starbucks, as if it was written in the halls of Empire. But it was not. It was written by brown, colonized people who were serially enslaved, and they were working out what it meant for them to be free.”

CRT won’t save us, though it could be a gift from God to help us on the journey of working out our own salvation with fear and trembling. But first we’ve got to turn off the TV and think as Christians. For as John warned us in his first letter, “If we claim to be without sin, we deceive ourselves and the truth is not in us.”

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor & Beau Underwood

This is an incredibly misleading and short-sighted summary of what CRT is as well as an excellent straw-man that only repeats talking points on both sides, but specifically the pro-CRT side. There wasn't one stance on the anti-CRT side that wasn't misconstrued to fit your argument. Not a good public witness of Christianity.