The War on Military Chaplains

President Joe Biden wants to court-martial Christian chaplains in the military. Well, that’s what some conservatives claim.

Such hyperbole came as Republican senators grilled the president’s nominee for one of the most high-profile positions in all of Washington, D.C.: the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Manpower and Reserve Affairs. Check that, it’s a position few of us knew even existed. But the hearing over Biden’s nominee reveals significant fault lines in our country regarding perceptions of how religion and state mix.

Brenda Sue Fulton, one of the first women to graduate from West Point, found herself under a barrage of attacks not from an enemy nation but the elected leaders of her own government during her confirmation hearing on Oct. 7. GOP Senators who defended former President Donald Trump after the Jan. 6 insurrection expressed hurt feelings over Fulton’s “inflammatory” tweets that criticized racism and Christian Nationalism displayed by members of their own party.

In the latest jarring example of political tribalism, senators who once professed ignorance of Trump’s profane tweets found themselves outraged that other public servants would express charged opinions on social media. Unlike the former president, Fulton apologized repeatedly in the hearing for the tone of her past words.

In particular, senators like Marsha Blackburn of Tennessee, Tom Cotton of Arkansas, Josh Hawley of Missouri, and Rick Scott of Florida attacked Fulton as “anti-Christian.” This misconstrual of her views conflicts with her own personal confession of faith. Rather than honest disagreement, this brouhaha seems a convenient forum for fueling culture war narratives and depicting the Biden Administration as antagonistic to religion in general and chaplains in particular.

“Military chaplains who adhere to traditional Christian teaching find themselves with targets on their backs in Joe Biden’s military,” a senior editor for the American Spectator claimed on Oct. 9. “In Biden’s America, military chaplains will be reduced to propagandists for the pols in power, not unlike the Orthodox clergy under the Soviets.”

The piece added that Fulton’s nomination was a conspiracy by Biden toward “liberalizing and de-Christianizing the military, since it is one of America’s most historically conservative institutions.” Thus, the piece predicted: “What would once have been considered unthinkable — the court-martialing of Christian chaplains for simply upholding perennial teachings of Christianity — is sure to figure into America’s future.”

So, what’s really going on? In this issue of A Public Witness, we interrogate the arguments about military chaplains in the recent confirmation hearing by the Senate Armed Services Committee. We also testify to the proper role of military chaplains and the problems with a misguided, sectarian approach favored by some senators.

Ever Hearing, Never Understanding

Fulton would bring a variety of experience to the role. She served as chair of the West Point Board of Visitors (the first female graduate in that position). Currently, she leads the New Jersey Motor Vehicle Commission. More personally — and related to criticism she received from Republican senators — she has advocated for LGBTQ inclusion in the military. She and her late wife were the first same-sex couple married at the U.S. Military Academy’s Cadet Chapel at West Point.

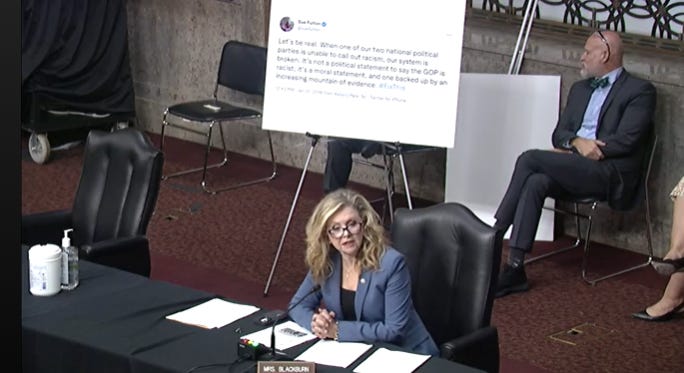

Sen. Blackburn brought “a stack” of Fulton’s tweets, some blown up on posters for increased visibility. After reading one critical of Republicans, Blackburn asked if Fulton thought Christians were “racist” and “nutjobs.”

“I’m a Christian, and no, I don’t,” Fulton replied. “I will, as I have throughout my career, work side by side with Republicans, with Democrats, with independents, with anyone regardless of their political beliefs, for the mission, for what is best for our Armed Forces.”

Sen. Cotton pressed Fulton over a tweet she offered seven years earlier in response to the U.S. Supreme Court’s controversial decision in the Hobby Lobby contraceptive case. Fulton wrote, “Once again, ‘religious freedom’ twisted to mean conservative Christians can dictate their beliefs to the rest of us.” Cotton complained about the quote marks around “religious liberty” and for the opinion that went against his interpretation. But Fulton wasn’t outside the mainstream of the public discussion. In fact, many groups advocating for religious liberty, like Americans United and the Baptist Joint Committee, similarly expressed concerns about the ruling.

“I support religious freedom, and I would support religious freedom for all of our troops, all of our civilian employees, consistent with the law,” Fulton responded to the senator from Arkansas.

Cotton also confronted Fulton for tweeting four years ago in response to the anti-LGBTQ “Nashville Statement”: “The vast majority of White evangelical leaders are utterly unmoored from the Gospel of Jesus Christ.” Cotton then asked if she could put a percentage on how many are unmoored, but she declined to take his bait — though we could recommend a book or two or three from Christian experts on that topic for the senator who once justified slavery as a “necessary evil.”

Then just moments after questioning if someone should attack any Christian as “unmoored from the Gospel,” the senator who previously attacked the faith of then-Democratic Sen. Mark Pryor and then-President Barack Obama, told Fulton he couldn’t vote for her because “you have a long history of offensive, inflammatory accusations against Bible-believing Christians.”

Sen. Scott lectured Fulton — without giving her a chance to respond — about the right that people have to hold and express their own beliefs. Without any sense of irony, he then questioned why she held and expressed her own beliefs back in 2011 when criticizing an “anti-gay, anti-abortion lobby that purports to represent Christians” since their “language and actions hold no resemblance to the Jesus I know from the Bible.” Scott added it was wrong for her to call conservative Christians “radical,” though the senator often brandishes that term in attacking liberals.

Sen. Hawley, who infamously raised a fist in support of the insurrectionists on Jan. 6, added to the litany of complaints in claiming that Fulton’s nomination was a sign of the Biden Administration’s “radical left agenda.” Hawley then proceeded to question her about how she applies some biblical teachings.

His questions stood in sharp contrast to previous exhortations made by Hawley to senators to avoid “anti-Christian, anti-faith vitriol” since “religious bigotry has no place in the United States Senate.” Hawley made those comments about the confirmation hearing for Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett, insisting the Senate shouldn’t “return to the days of ‘religious tests’” where nominees are questioned on their theological beliefs

Of course, his ire then — along with that of his GOP colleagues — was aimed at troubling comments from Democratic Sen. Diane Feinstein towards Barrett that “the dogma lives loudly within you.” But when it’s the “other side” with a nominee for the Senate to consider, Hawley took up the dogma questioning.

In response to Hawley’s questions, Fulton reiterated her support for religious freedom and her own Christian faith as “a follower of Jesus Christ.” She added, “None of what I’ve ever expressed on social media was intended to silence others. I believe there’s a free expression of beliefs there.”

Priests of the Secular

Looking beyond the political and cultural issues at play, this strange episode around Fulton’s nomination is revealing of misconceptions around the duties performed (and not performed) by military chaplains. Their purpose is not to advance the beliefs of their particular faith tradition but to serve the spiritual needs of all those under their charge, regardless of a soldier’s particular religious identity.

In her book A Ministry of Presence: Chaplaincy, Spiritual Care, and the Law, religious scholar Winnifred Fallers Sullivan examined the expanding role of chaplains in American society. Inherently religious, humans continue to need spiritual care despite less connection to organized communities of faith. Chaplains serve as shepherds not to a specific flock of like-minded believers but to those coming under their care because of illness, war, incarceration, education, or even catching a flight.

“Chaplains trained by religious communities minister to a clientele often unmarked at that moment by any specific religious identity, and they do so on behalf of a secular institution bound, at least theoretically, to rational epistemologies,” Sullivan wrote. “The chaplain has, without paradox, become a priest of the secular.”

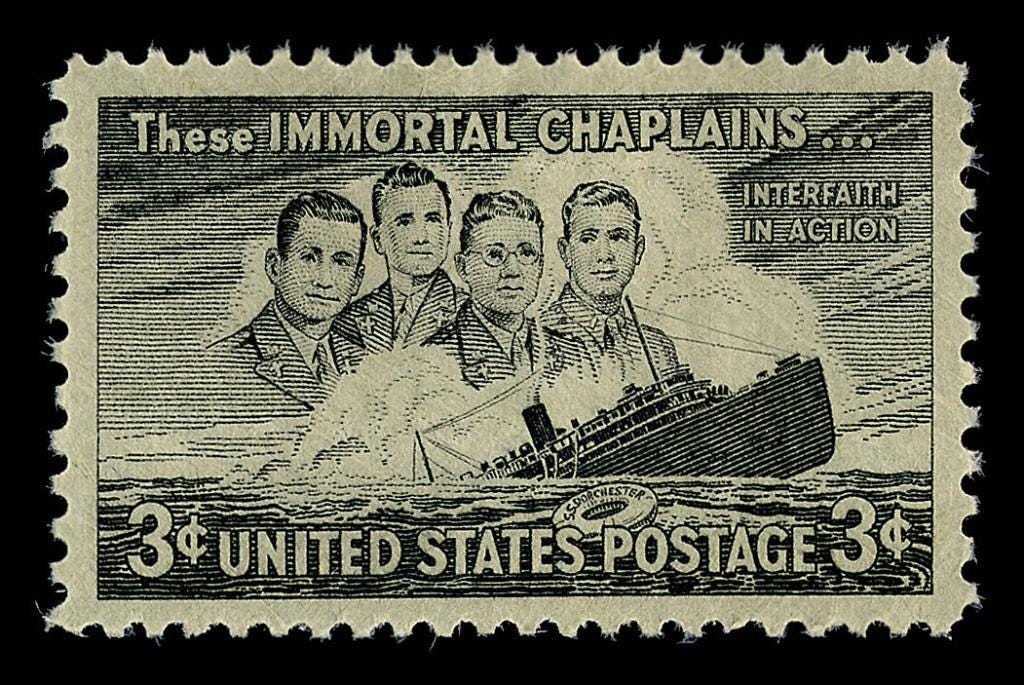

Military chaplains are not exempt from this logic. Indeed, rather than being “one of America’s most historically conservative institutions” as the editor of the American Spectator claimed, an actual examination of historical events reveals the innovative role played by military chaplaincies within the American religious landscape.

Historian Ronit Stahl documented this trend in her book Enlisting Faith: How the Military Chaplaincy Shaped Religion and State in Modern America. She detailed how changes in military policy related to chaplains altered the practices of Christian denominations and other religious groups within the United States. Seeking the legitimacy bestowed by inclusion within the military chaplain corps, faith traditions advocated for inclusion and conformed to the expectations required for participation.

Moreover, this aspect of military life became a force for broader social change. Steps taken to foster greater inclusion within the armed forces following World War II fostered a greater recognition and acceptance of religious pluralism within civilian life.

And for the military, the work of the chaplain has always served a pragmatic purpose. Writing about the young men drafted into service during World War I, Stahl highlighted the valuable role military chaplains played in integrating soldiers into their newfound roles and, even more importantly, keeping them out of moral trouble.

“Chaplains therefore conducted a very particular type of religious work,” she explained. “As clergy vetted and approved by the state, they would transcend religious differences to buoy the spirits, discipline the bodies, and yoke together the hearts of doughboys.”

The military employs chaplains to serve its own strategic ends. Their work supports troop readiness and provides spiritual care to uprooted soldiers asked to leave behind everything, including their own house of worship.

Breaking Ranks

Just as the government generally cannot privilege or establish one religious sect over others, chaplains who see the military as fertile ground for proselytizing sow discord rather than contribute to valued unity. Such division disrupts the pragmatic purpose of the chaplaincy program.

As Fulton made clear in a response to Sen. Jim Inhofe, “Our chaplains are bound and do a remarkable job addressing all of the needs, one way or another, of our service members.” She added, “Anyone who wears the uniform of this country has certain constraints on what they can say in public, and certain requirements to serve others and to serve without regard to whatever personal feelings they may have.”

That’s the role of a military chaplain. But her critics apparently pray for a more sectarian model that could leave many service members without spiritual support if they don’t meet the religious test employed by clergy.

Consider, for instance, a question from Sen. Cotton to Fulton as he asked if she was “actually going to protect the religious freedom of troops and chaplains, or are you going to ensure that they can’t ‘dictate’ their views to the rest of us?” The dichotomy Cotton offers is that Fulton either has to allow chaplains to dictate their views or she is violating the religious liberty rights of the chaplains. But that’s a twisted view of “religious liberty” (and yes, Sen. Cotton, we did put it in quote marks because we don’t think that term means what you think it means).

Defending the true religious liberty rights of military service members means chaplains cannot be allowed to dictate their faith. To suggest otherwise is to fundamentally misunderstand the role of military chaplains.

Some senators pushed back during the Oct. 7 hearing. Sen. Jack Reed, a Democrat from Rhode Island, defended Fulton after the attacks by several of his Republican colleagues. Chairing the hearing, Reed said, “There’s been no complaints by any of your subordinates or any of your superiors about your work” including as she worked with people with “political, theological, ethnic differences.” Thus, he defended Fulton for doing her job without letting “private thoughts and ideas ... influence your professional activities.”

With these remarks, Reed did more than just point out how Fulton hadn’t tried to enforce her religious beliefs on others in her government roles. He also ended up exposing what was missing from the complaints by his colleagues on the other side of the political aisle. While Republicans criticized Fulton for her religious and political beliefs, none offered proof she had actually misbehaved as a government administrator, nor did they even ask about how she managed such tensions in the past.

Thus, GOP senators did exactly what they say, without evidence, Fulton would do if confirmed: They announced they would punish her from their official capacity because they disagreed with her sincerely-held personal religious beliefs.

Whose Christianity?

Embedded within this theological disagreement is a subtle move by some senators to change the terms of the debate and define Fulton out of her own faith tradition. One does not need to agree with Fulton’s theology or tweets to see the problem with what her critics are trying to do. In her controversial tweets and statements, she criticized “right-wing” and “conservative” Christians in response to specific events. But her senatorial interrogators often dropped those adjectives.

In doing so, they assert that their narrow wing of Christianity represents the entirety of the faith. Such a rhetorical sleight of hand helped them frame Fulton as “anti-Christian” instead of accurately depicting her criticisms as applying to a strand within American Christianity. Having imposed their definition, they ostracized Fulton as beyond the boundaries. They made her into a heretic threatening their orthodoxy.

So, Sen. Cotton claimed Fulton went after “Bible-believing Christians,” making the common fundamentalist error of castigating those with a different interpretation of the Bible as not believing in scripture or even counting as a Christian. Sen. Blackburn even conflated Fulton’s criticism of Republicans as criticism of Christians, which seems like quite the tell in revealing the senator’s worldview.

This narrative, of course, ignores and delegitimates the millions of Christians like Fulton who support women in leadership roles, welcome LGBTQ people into churches, and are inspired by their faith to take progressive political stances. In misconceiving the nature of military chaplaincy, these senators misconstrue the diversity of Christianity in the United States.

This is why the American Spectator editor can write that with the nomination of Fulton, Biden “couldn’t make his contempt for Christian America any clearer.” Given the depth of Biden’s own Christian faith, his re-establishment of the White House faith-based office, and broad support from many Christian leaders, this absurd sentence only makes logical sense if “Christian America” is defined in a very narrow, nakedly partisan way.

Some GOP senators and conservative media outlets are trying to redefine Christianity for their own political benefit. They want to decide who’s in and who’s out, what counts as “Christian” and what is out of bounds. And they want to stamp that vision on the military and its chaplains.

Nobody elected or ordained the senators to that task. Thank God.

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor & Beau Underwood

Brilliant - and thank you. Amazing how ignorant these senators are about chaplaincy. But they clearly know their audience, which is clearly their only concern. The campaign for christian nationalism still has representation, and in very high places.