What Congress Reveals About the Methodist Schism

When former South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley officially announced her presidential campaign in February 2023, she embarked on a journey to become the first woman and only the second United Methodist layperson to take the presidential oath of office. If she pulls off a historic primary upset against former President Donald Trump and then defeats President Joe Biden, she would still be the first female president. But George W. Bush would keep his title as the sole United Methodist to sit behind the Resolute Desk. (Rutherford Hayes and William McKinley were also both Methodists but before the creation of the United Methodist Church in 1968 from the merger of older denominations.)

Less than two weeks after Haley launched her campaign, 97% of her longtime congregation in Lexington voted to leave the United Methodist Church (UMC). Like most others in the exodus of churches disaffiliating from the UMC in recent years, her church left because they oppose the recognition of same-sex marriages and clergy. The largest Methodist congregation in the Palmetto State, the church joined the Global Methodist Church (GMC), a new denomination launched in 2022 for conservative churches departing the UMC.

Polling suggests Haley is unlikely to become the first president from the GMC. But her campaign at this time of schism within the UMC highlights the potential cultural impact of the divide that saw one-quarter of the nation’s UMC churches depart over the last four years. With the deadline for the recent disaffiliation process having ended on Dec. 31, 2023, the dust is still settling to understand what this means for Methodists or the broader American society.

United Methodists have long cherished their role in influencing public policy. They boast of owning “the only non-government building on Capitol Hill.” The United Methodist Building, which predates the UMC itself, has been the center of Methodist public witness for over a century. Sitting next to the U.S. Supreme Court building and across the street from the U.S. Capitol, its sign out front often functions a lot like a pithy church sign but with politically charged messages to promote justice to its powerful neighbors. Like one in 2018 after U.S. border agents used tear gas on migrants: “‘I was a stranger, and you tear gassed me.’ …Wait a second.” Or one just before the 2020 election: “Hope Act Vote and Wear a Mask.”

In addition to losing one-quarter of its churches during the recent schism, the UMC also lost some of its prominent political members like Haley. Such losses go beyond bragging rights or political influence; they provide insights into the new makeup of the UMC and the leanings of the fledging GMC. The North-South schism of Methodists in the 1840s helped lead the nation toward a Civil War. What might the new divide tell us about religion and politics?

One way to consider the potential religious and social impact of the UMC split is by looking at the membership of Methodists in the U.S. Congress. So this issue of A Public Witness tracks which members of Congress are no longer part of the UMC to consider what that reveals about Methodist life and the broader Christian witness.

Finding Congressional Methodists

Every two years as a new session of Congress begins, Pew Research Center releases a report analyzing the religious composition of the House and Senate (which is based on self-reporting of religious affiliation from congressional offices to CQ Roll Call). For the 118th Congress, which started in January 2023, Pew noted the general category of “Methodist” included 31 members. However, the data does not note which Methodist denomination or if the members actually attend somewhere.

For this analysis, I started with Pew’s list of 31 Methodist lawmakers. By checking congressional biographies and social media accounts, searching for news reports, and reaching out to congressional offices, I connected most of the members to a congregation.

I removed several Methodist lawmakers from this analysis of the UMC because they are part of different denominations. Three members are in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, a historically Black denomination formed in 1816 because of the racism of White Methodists. Another lawmaker is part of the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church (another historically Black body), and one lawmaker is in the Congregational Methodist Church (a small, historically White body primarily in the South). I excluded two additional lawmakers who self-identified as “Methodist” but have instead publicly shared that they attend a church of a different denomination.

That left 24 “Methodist” lawmakers. Of those, I was able to find a local congregation for 21 of them that put them in the UMC in 2019. It’s possible the three missing ones (two Democrats and one Republican) aren’t actually attending or connected to a church but still identify as Methodist.

Additionally, I found seven other lawmakers who are part of congregations that were affiliated with the UMC before the split. These lawmakers were listed in Pew’s data as “Protestant unspecified,” a generic term that’s been growing in use by congressional members in recent years.

Altogether, this gave me a list of 28 lawmakers who were part of congregations in the UMC in 2019 — 16 Republicans and 12 Democrats, 24 representatives and 4 senators. I then researched the churches’ denominational affiliation of Jan. 1, 2024, to examine how the UMC schism played out for members of Congress.

Disunited Methodists Under the Dome

According to a report released this month by the Lewis Center for Church Leadership (a research center at the UMC-affiliated Wesley Theological Seminary), 7,631 congregations left the UMC between 2019 and Dec. 31, 2023. The disaffiliating churches represented 25% of UMC congregations and 24% of UMC members in the United States.

Among Methodists in Congress, the percentage who are no longer in the UMC is a bit higher. Of the 28 UMC lawmakers, 9 (32%) are part of congregations that disaffiliated. At least six of those churches have joined the Global Methodist Church.

For instance, First Methodist Church in Waco, Texas — the congregation of Republican Rep. Pete Sessions — left the UMC and joined the GMC. In January 2023, the church hosted the inaugural session of the Mid-Texas Annual Conference of the GMC (the first GMC conference to convene), and the church’s pastor is listed as a leader of the conference.

Similarly, the church of Republican Rep. Trent Kelly of Mississippi — Saltillo Methodist Church — voted with 98.5% agreement to leave the UMC, and has since joined the GMC. However, Kelly hasn’t yet updated his official congressional biography that still lists his church by its old name before it dropped the word “United.”

For the churches of some lawmakers, the process to leave sparked legal battles. The church of Republican Rep. Rick Allen of Georgia — Trinity on the Hill in Augusta — sued the North Georgia Conference of the UMC after their bishop attempted to delay the church’s disaffiliation. The church noted it wished to leave the UMC because of its opposition to LGBTQ+ ordinations and marriages. A judge ruled in favor of the congregation, and more than 180 other churches in the conference later won a similar suit. Allen’s congressional biography still lists his church by its old “United” name.

The legal outcome wasn’t as favorable for the church of Republican Rep. Bill Posey of Florida. Rockledge Methodist Church, where he has served as a trustee, joined more than 100 other churches that sued the Florida Annual Conference of the UMC to challenge the payments the local conference was requiring from exiting churches. The suit alleged their bishop violated the UMC Book of Discipline by not taking action against LGBTQ+ individuals in the UMC and thus the churches shouldn’t have to follow the rules to disaffiliate. A judge dismissed the suit. Rockledge proceeded to leave the UMC through the outlined process, and the church joined the GMC.

Although the proportion of departing UMC members of Congress is slightly higher than the percentage of UMC members overall, a significant difference emerges when comparing Republicans and Democrats. All 12 Democrats who were UMC members before the split are still part of the UMC — including Rep. Emanuel Cleaver II of Missouri, an ordained UMC minister. However, among the 16 Republicans, a slight majority of their congregations — 9 (56%) — disaffiliated.

Beyond the act of staying, some of the churches of congressional Democrats make clear they support LGBTQ+ inclusion in UMC life. Such as Greenland Hills United Methodist Church in Dallas, Texas — the church of Democratic Rep. Colin Allred — that describes itself as “a Reconciling Congregation of the United Methodist Church that welcomes people of any sexual orientation or gender identity.”

Meanwhile, the churches that left the UMC did so through the process created to allow disaffiliation because of disagreement over LGBTQ+ issues. And many of them also highlighted that issue publicly as they left. For instance, Dardanelle Methodist Church in Arkansas — the home congregation of Republican Sen. Tom Cotton — voted with an 86% supermajority to leave the UMC. The church, calling itself part of a movement of “traditional believing Methodists” joining the GMC, explained it took the move because it “felt disenfranchised with the progressive agenda [UMC] bishops had adopted, and disagreement over the authority of scripture.”

Simply because a church left or stayed does not mean an individual lawmaker agrees with that decision (or voted that way if they attended the meeting). Across Methodist life there are some members staying with their longtime congregation even if they disagreed with the denominational vote, but there are also others leaving from both sides of the split to form new congregations if their preferred denominational choice didn’t win.

At most of the churches of congressional Methodists, the vote to disaffiliate either passed overwhelmingly or the church didn’t even vote because it was already a welcoming and affirming congregation in agreement with the direction of the UMC. However, the issue was divisive at First United Methodist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, the home congregation of Republican Sen. Katie Britt. Some lay leaders in the congregation attempted to start the discernment process that could have led to a disaffiliation vote, but that effort failed as they couldn’t get the pastor’s support needed for the local conference’s process. Some members reportedly left to form a new GMC church.

It remains to be seen if any lawmakers will switch churches because of the denominational turmoil. Although it seems implausible a Democrat would leave a church for staying in the UMC, perhaps a Republican will move from a UMC church to find a GMC or other conservative alternative. On the other hand, some members may not actually be connected enough to the life of their congregation for that to be a concern, and there are a number of conservative lawmakers who remain in local churches of liberal denominations like the Episcopal Church.

The differences between the congregations of Democrats and Republicans align with some of the findings in the Lewis Center report on overall UMC disaffiliations. They noted that the one-quarter of congregations that left the UMC were “disproportionately White” as 97.4% of disaffiliating churches were majority White. All of the Black lawmakers in this analysis are Democratic and still in the UMC.

Additionally, the report found that disaffiliating churches disproportionately came from the southeastern region (50% of all disaffiliations) and the south central area (21% of all disaffiliations). All nine lawmakers in churches that left the UMC came from eight states in those two Republican regions — five in the southeast area and four in south central region. In addition to Sessions, Kelly, Allen, Posey, and Cotton, the other Republican lawmakers no longer in the UMC are Rep. Richard Hudson of North Carolina, Sen. John Kennedy of Louisiana, Rep. Thomas Massie of Kentucky, and Rep. Troy Nehls of Texas.

Red and Blue Denominations

The U.S. Constitution prohibits religious tests for office. This analysis isn’t meant to question the denominational affiliations of any member. Lawmakers should be judged on their policies, not where they attend worship (or not). This analysis instead tells us more about Methodists than it does Congress.

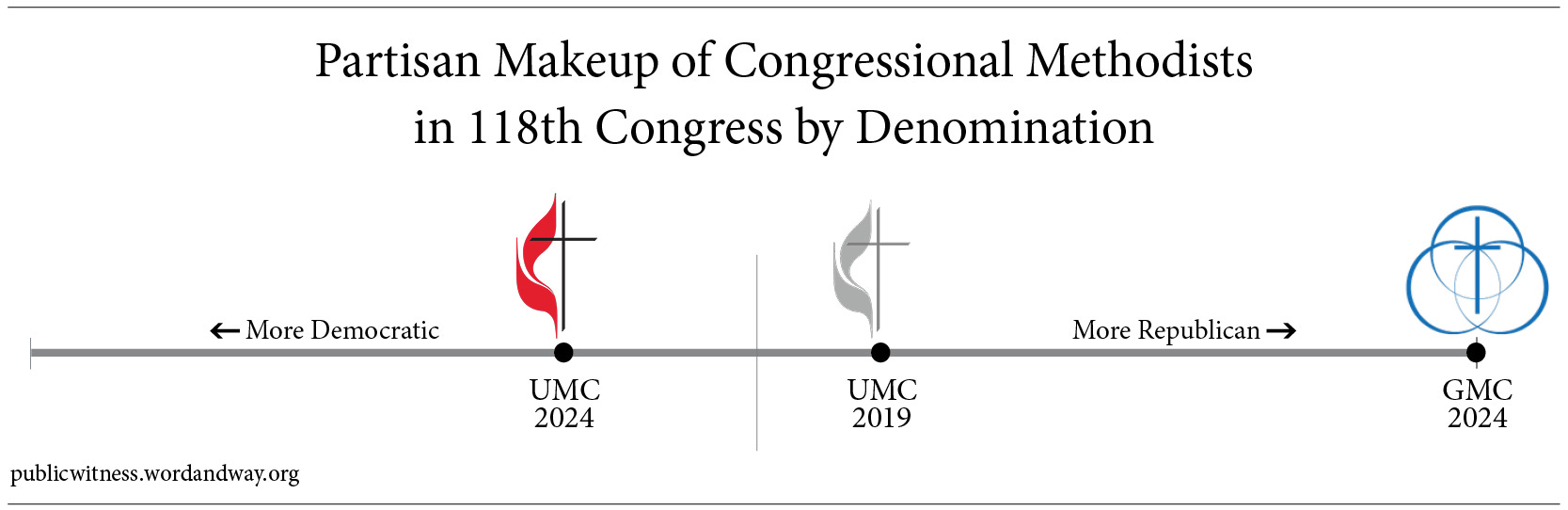

The members of the 118th Congress showed a denomination that without the split would’ve been well represented by both parties. The Republican lean (57%) still meant a significant minority were Democrats. Such a congressional delegation represented the bipartisan denomination overall. As Pew Research Center found, 45% of UMC members identified as conservative, 15% as liberal, and 38% as moderate. UMC clergy, as PRRI has highlighted, were more Democratic and more liberal than churchgoers but still represented the ideological continuum better than most mainline denominations.

The current UMC congressional representation (63% Democratic) aligns more closely with the Democratic leanings of UMC clergy, though it moves away from the majority of UMC members before the split. The denomination overall — clergy and those in the pews — has undoubtedly shifted leftward as the one-quarter of disaffiliating churches would’ve largely come from the congregations with more conservative (and Republican) clergy and members.

To be clear, the UMC still includes some prominent Republicans in public life. In addition to Sen. Britt of Alabama, its congressional membership includes conservative Republicans like Freedom Caucus member Rep. Dan Bishop of North Carolina and multiple members who voted to overturn the 2020 presidential election. Mississippi Gov. Tate Reeves is also still a UMC member. Additionally, two prominent Republicans who were criticized in recent years by some Methodist clergy are part of churches that stayed in the UMC: President George W. Bush (who was criticized by UMC leaders for the invasion of Iraq) and Attorney General Jeff Sessions (who was accused by hundreds of UMC members of violating church rules by enforcing Trump’s child separation immigration policy).

While the UMC delegation in Congress has shifted leftward, more than one-third are Republican. Significant alternative political perspectives still exist within the UMC family. Future surveys of UMC members will likely similarly find a leftward shift but also still a faith tradition with some political diversity.

For the new GMC, however, the group starts out with a congressional delegation that is 100% Republican. While the UMC percentage of Republicans and Democrats in Congress shifts every two years as some members retire, are defeated, or are elected for the first time, the GMC membership in Congress seems much less likely to move given the sharp ideological line that led to the convention’s formation.

With the GMC on one extreme of the continuum, what does it mean for a faith tradition to have such a partisan bias among its members in office? Assuming the clergy and membership are also overwhelmingly conservative, what will it mean for a faith tradition to lack the diversity of perspective found in the UMC before and after the split? Will it be easier for denominational leaders and clergy to engage in partisan politics since they know they won’t face much pushback internally? Will it be easier for churches to fall into partisan groupthink since they will frequently lack political diversity within their sanctuaries?

As Christian communities divide into blue denominations and red denominations, it will become more likely that Christianity gets caught in the political crossfire and used as a partisan tool. And like the North-South Methodist split that prefigured the Civil War, the UMC-GMC split doesn’t bode well for addressing the deepening partisan divides in our nation’s capital.

“In the past, when churches split over politics, it was a sign that country was fast coming apart at the seams,” historian Joshua Zeitz, author of Lincoln's God: How Faith Transformed a President and a Nation, wrote at Politico. “Today, mainline churches are buckling under the strain of debates over sex, gender, and culture that reflect America’s deep partisan and ideological divide. In a country with a shrinking center, even bonds of religious fellowship seem too brittle to endure. If history is any guide, it’s a sign of sharper polarization to come.”

As Congress shows, the polarization in Methodist life has already sharpened quite a bit.

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor

This is extraordinary in details and an important analysis of religion and politics. It is much more nuanced than anything I've ever read on the impact of denominational tensions and splits on political issues in recent history.

There are echoes here of the ways in which the big historical split in Methodism -- the one before the Civil War -- shaped subsequent American history.

The question that comes into my mind: The 19th century split mattered politically in forming the political culture that led to the Civil War. The early 21st century tensions certainly resemble that past pattern. But how much difference does the overall decline in religious adherence and the marginalization of religion in American life change the potential historical consequences of denominational splits? Can we integrate more general religious trends into this truly fine analysis of denominational/political transformation?

It seems obvious that Methodism is no where near the cultural force it once was -- and that what is a genuinely significant historical moment for a formerly important American institution may wind up be so culturally diluted by larger trends that the split won't ultimately matter to American politics. But it will contribute to the continued decline of white American Protestantism -- as Protestantism itself is increasingly seen by secular Americans as co-terminus with white Christian nationalism and MAGA.

Fantastic and important post, Brian. Kudos.

Thank you for this excellent analysis!