Review & Giveaway: God Gave Rock & Roll to You

Contemporary Christian Music (CCM) was the soundtrack to my teenage and young adult years. Jars of Clay, David Crowder, MercyMe, and other groups dominated my car stereo. The first concert I attended was headlined by Sonicflood. At the invitation of a friend, I attended an intimate concert with Bebo Norman long before others had heard of him or listened to his music.

I enjoyed the music. I even found inspiration from it. Yet, there was always something awkward about my fandom. I would love the concerts but cringe during the transitional moments in the show where certain types of missionary efforts or social causes were pitched that conflicted with my own beliefs and theology. Listening to the radio, I quickly became aware that much of the non-musical content idealized and supported a “traditional” social order that I found anathema.

And, of course, there were the lyrics. While the songs were catchy, a lot of the theology hiding in the lyrics was terrible. Some of the political and social messages were subtle and others quite overt. For example, “What If His People Prayed” by Casting Crowns got lots of Christians singing:

And what would happen if we prayed

For those raised up to lead the way

Then maybe kids in school could pray

And unborn children see light of day

What I — and so many others — lacked was the context necessary to make sense of what I was hearing. I was ignorant of the historical influences that fueled the rise of CCM, the roles it played within the conservative Christian subculture, and the agendas of those who put its messages out into the world.

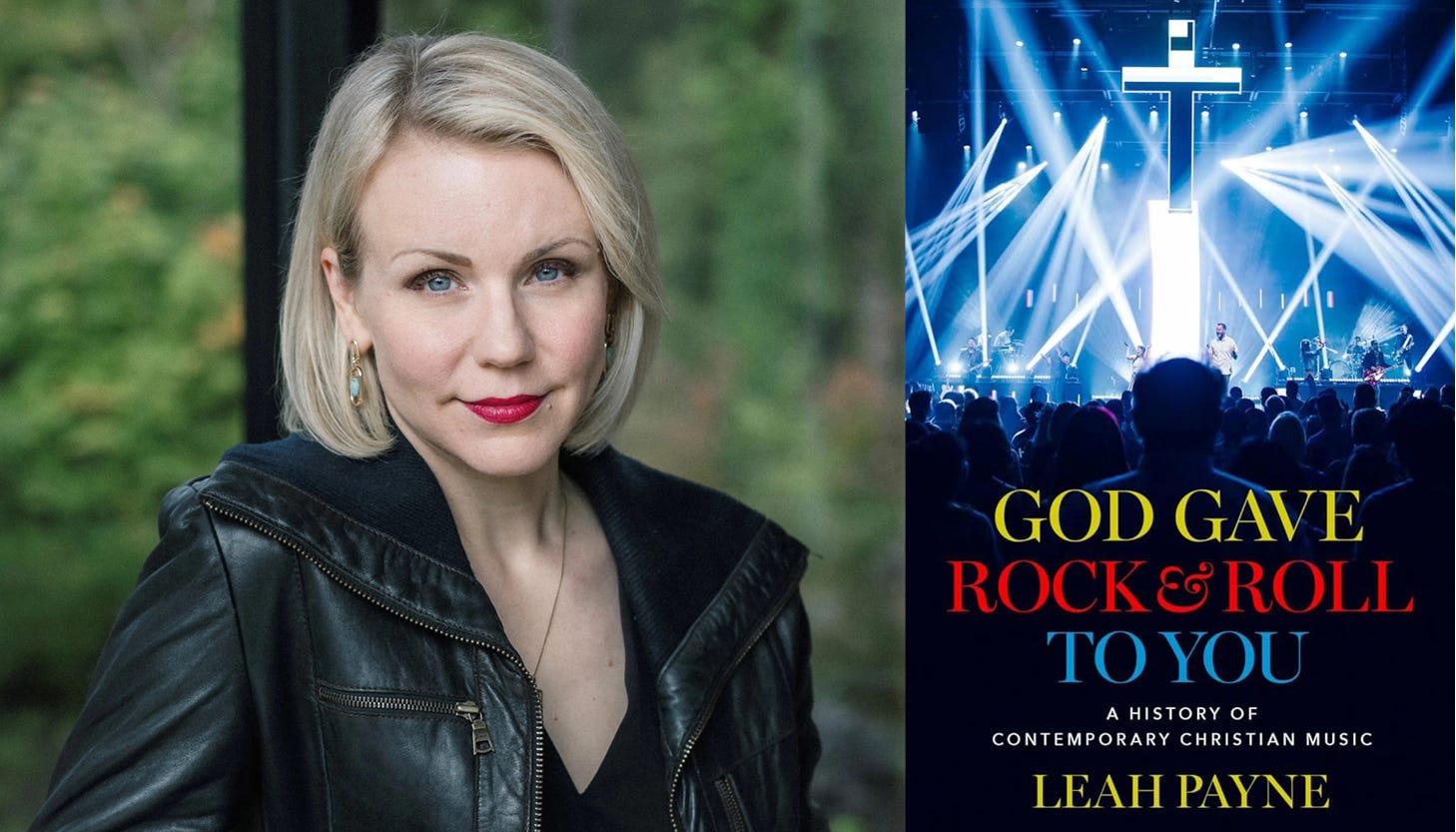

Leah Payne’s God Gave Rock & Roll to You: A History of Contemporary Christian Music provides a great adventure into understanding all of that. As she explained in introducing her topic, the project sees “CCM charts as representative of a conversation among (predominantly, but not exclusively White) evangelicals about what kind of people they wanted to be, what sort of world they wanted to create, what kind of actions they thought would honor God.”

I could only imagine the countless revelations Payne’s book contains when I first opened its pages. You’ll learn about CCM’s origins in White Southern revivals and gospel music that promoted nostalgia for “old time religion” and reinforced racialized hierarchies. Publishers and promoters quickly learned there was money to be made in catering to the sentiments of Christians struggling with how society was changing.

She also explained how various mediums and technologies that some Christians were suspicious of were embraced as a way of advancing biblical causes. While some dismissed radio as being a demonic toy, Aimee Semple McPherson, Billy Graham, and others demonstrated its power to reach mass audiences with Christian messages and music. Rock-and-roll presents both threat and opportunity, with the power to lead masses of people away from Jesus or to be co-opted by Christian musicians for advancing the gospel.

While Payne’s history of how the CCM movement began and matured is fascinating, even more interesting is her analysis of the social context surrounding and emerging from this movement. For example, the connections she highlighted between CCM artists and the advancement of a “purity culture” within conservative evangelicalism make clear how the music was always about so much more. The effort to define femininity, gender roles, and sexual ethics in a way that was more Victorian than Christian received serious assistance from CCM.

“Youth pastors often found that attractive young CCM artists made the best messengers when it came to teaching about purity culture,” Payne wrote, adding that this cultural push “disproportionately emphasized women’s sexual purity. ‘Purity balls,’ events where dads (or prominent male caregivers) brought their post-puberty daughters together to dance to CCM virginity anthems, sprang up around the country, propelled by endorsements from Focus on the Family.”

The book covers a range of other topics you’d expect as well: the disillusionment and deconstruction among some prominent artists, the role of megachurches in shaping and sustaining CCM, the negative effects radio’s decline has had on the industry, and — of course — the complications and compromises created by Donald Trump and our current political polarizations.

“Tour de force” is a phrase that should not be thrown around lightly, but God Gave Rock & Roll to You is a book that earns that description. It’s a volume that will be required reading for any person wanting to understand how American Christianity, especially evangelicalism, evolved through the 20th century. And it will be the starting point for anyone wanting to understand the complexities of CCM’s place in this world. Whether you grew up a CCM fan or never listened, it’s a book you should read twice and then make sure someone else reads as well.

Between you and me, Payne has agreed to send an autographed copy to one Jesus Freak who is a paid subscriber to A Public Witness. If you haven’t already, upgrade your subscription today and you might be the lucky winner who enjoys that beautiful ending.

As a public witness,

Beau Underwood

Thanks for this, Beau. This resonates, especially after just reading a 1995 journal entry about riding to youth group with Audio Adrenaline and Newsboys on the discman. As an adult, I want to be in the light as much as any Jesus Freak, but I wish we'd all been ready to distinguish the cultural detritus mixed in with sometimes fine theology of the music of our youth. Day by day, I'm figuring this out now, and I can't wait to read the book. I'll give you a wild guess what my first concert was :)